The Adventure of English (16 page)

Read The Adventure of English Online

Authors: Melvyn Bragg

In 1589, George Puttenham, the author of the rhetoric manual

The Arte of English Poesie,

wrote that:

ye shall therfore take the usuall speach of the Court, and that of London and the shires lying about London within lx myles, and not much above. I say not this but that in every shyre of England there be gentlemen and others that speake but specially write as good Southerne as we of Middlesex or Surrey do, but not the common people of every shire to whom the gentlemen, and also the learned clarkes, do for the most part condescend.

Puttenham's distinction between written English â which could, he says, be of quality in whatever part of the country â and spoken English outside the charmed spell of Middlesex and Surrey is an early and acute insight.

How does that compare with English today? In terms of newspapers, magazines, essays, books of scholarship, and most poetry, drama, film and fiction, the language has been largely consolidated as “that of London.” Yet the written word in television drama has decisively broken away from that, and often with success:

Coronation Street

is Britain's most popular soap over its forty years even though its writers use a heavily accented northern tongue.

EastEnders

poses an intriguing problem. Though London based, it is not written in the sort of London language George Puttenham was describing in 1589. Yet it also reaches out to millions of understanding English speakers.

There are similar exceptions in poetry, fiction and drama, but fewer. On the whole, Puttenham's world is already recognisably our contemporary literary world and yet our most overwhelmingly popular medium is television, whose writers can claim audiences per episode of twelve to eighteen million compared with, say, the two hundred to three hundred thousand who eventually read a successful literary novel or the fifty to a hundred thousand who will read well-reviewed modern poetry. So whose English has it?

The easy way out is to dismiss television writers as “popular.” It might be relevant to note that the early East End novels of Daniel Defoe were also designated by the status-setters of the time as merely popular. Perhaps because they were poor novels. And

EastEnders,

like other soaps, cannot, I think, compare with the best plays, novels and films being written now. But it has never been a clever bet to disregard the potential energy in what is so very popular. Defoe went on to be one of the founders of English journalism and the English novel with

The Journal of the Plague Year

and

Robinson Crusoe.

Surely that could never happen with soaps? Yet Estuary English creeps in and shows no sign of ebbing.

Until quite recently, the Puttenham thesis would have been wholly unchallenged. Sir Thomas Elyot, of the Inkhorn Controversy on the side of tolerance and inclusiveness, advises in his

Governour

that the nurses who look after the children of noblemen in their infancy should speak an English which he says should be “cleane, polite, perfectly and articulately pronounced, omittinge no lettre or sillable,” rather as medieval commentators had enjoined that the women who looked after the Norman-French children should speak to them only in good French. Everybody knew what the ruling tongue was â and on the whole they knew they had to ape it to succeed. It is not quite as clear-cut today.

The struggle for the “right and proper” ways to speak was and is a continuing debate. Sir Walter Raleigh's Devonshire accent was strongly remarked on. Local accent was a matter of comment for a long time. Wordsworth's Cumbrian accent was noted at the end of the eighteenth century; D. H. Lawrence's Nottinghamshire (and his dialect in poems and short stories) at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries; William Faulkner's southern American in the mid twentieth; Toni Morrison in the late twentieth century. But on the whole these were exceptions: the standard was established in London, in New York, in capitals everywhere.

The Renaissance saw the beginning of the great writing rift, the splitting away of literature from everyday speech. Dialect words and terms often made an appearance in the work of major mainstream writers â Mark Twain, Rudyard Kipling and Thomas Hardy, for instance â but dialect writing was and is still, largely, thought to be below the salt. On the whole, literature still belongs to the high table, as George Puttenham indicated in 1589, and realists of the sixteenth century saw this and identified it. Writing had its own web to spin, its own written rhythms to discover, its own silent world to plumb and most of it was thought and aimed to be above common speech.

In the sixteenth century, dialect began to be considered uncouth, while at the same time it was admitted to contain energy. The story has not changed much since. In the late sixteenth century the dialect in southern Kent was possibly considered the most clumsy. It was used to indicate ignorance and foolishness on stage. Some of the early comedies like

Ralph Roister Doister

(about 1550) have characters using “ich” for “I,” “chill” for “I will” and “cham” for “I am.” It was considered positively rustic â and therefore funny and to be condescended to â to say “zorte” for “sort” and “zedge” for “say.”

But the juice in the dialects and local tongues did not dry up because of the laughter of London. They were to dig in for an astonishing number of years, over four centuries in some cases, and a few, even today, are going strong. Scotland provides the most vivid examples.

For centuries the streets of London had developed their own street slang. Crown and finance were centralised in London: so were rogues, thieves, prostitutes and criminals. There was so much interest in the language of vagabonds and thieves that a number of glossaries were published, such as John Awdely's

The Fraternyte of Vacabondes

(1575). So we know that “cove” meant man, “fambles” meant hands, “gan” was mouth, “pannam” was bread and “skipper” was barn.

Shakespeare was to use courtly English, street slang and his own local dialect. For much of the sixteenth century troupes of actors had been travelling England, performing plays and easily incorporating local dialects to heighten the effect and please the local audiences. These performances could be dangerous events and near riots are recorded at some of them. But it was these men (all men then) who knew that the mix, the spoken mix of high and low, of the beautiful high flow of Sir Philip Sidney, set alongside Ralph Roister Doister and the fast gang slang of Southwark, was combustible on stage.

Eventually these acting troupes settled in open-air theatres in London, the first in 1576. From 1583, the court had its own troupe of players, called The Queen's Men, who also toured the country. Those players were not speaking the new upper-class language of the poets, nor were they concentrating on the language of the streets. They had found a theatrical language, a way to address people across class and educational lines, to reach the majority. For wherever they played they were such a unique event in that town's history that it was the majority who turned up and paid and wanted to be pleased.

They roared into London and set up their theatres in Southwark. It was the principal nest of crime in the capital, it was filthy, crowded and dangerous, but it was cheap and next to the river for the convenience of those afraid to walk. It was also outside the City of London and hence the jurisdiction of the City Fathers who tended to deal with actors under the harsh laws against vagrancy. The Globe was built there in 1599. On these popular communal stages, something extraordinary happened which was to ornament, deepen, mine and charm English into a language capable, it seemed, of taking on anything, any thought, any action, any story, any feeling, any drama.

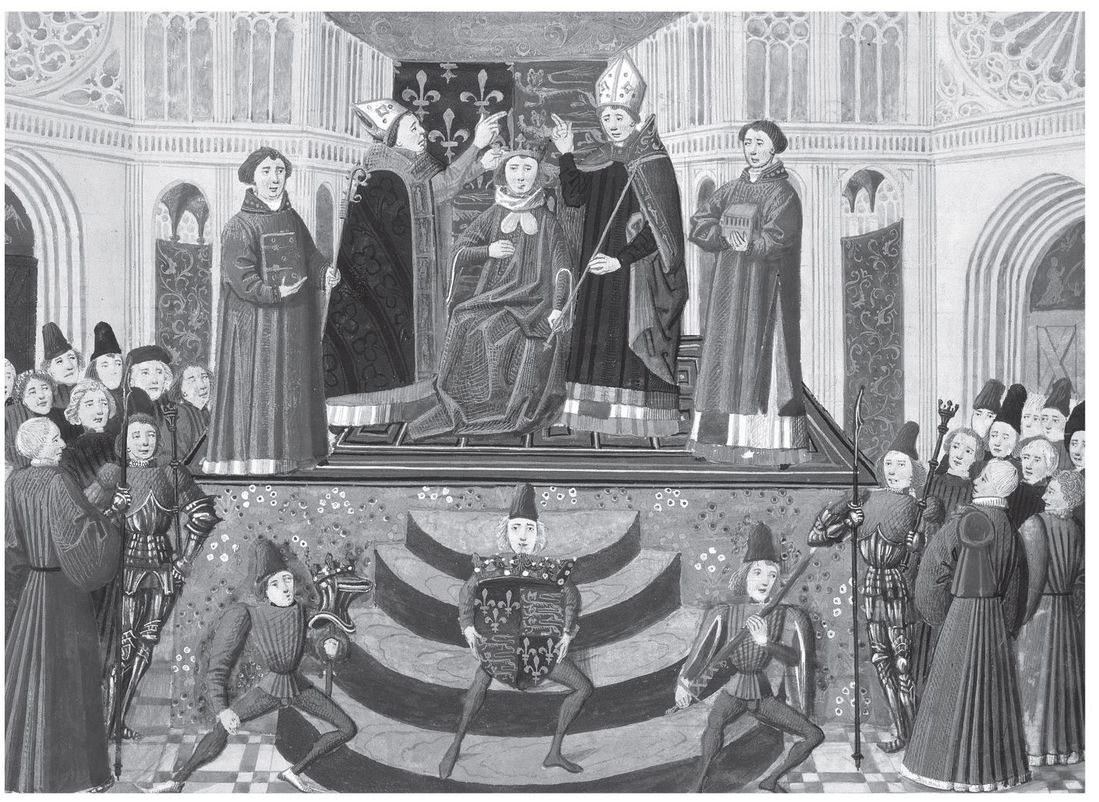

12. The Peasants' Revolt, 1381: Richard II, the boy king, met Wat Tyler at Smithfield and addressed his subjects in English, the language of the people.

13. When Henry IV was crowned in 1399 he made his speech in what the official history calls “His Mother Tongue” â English.

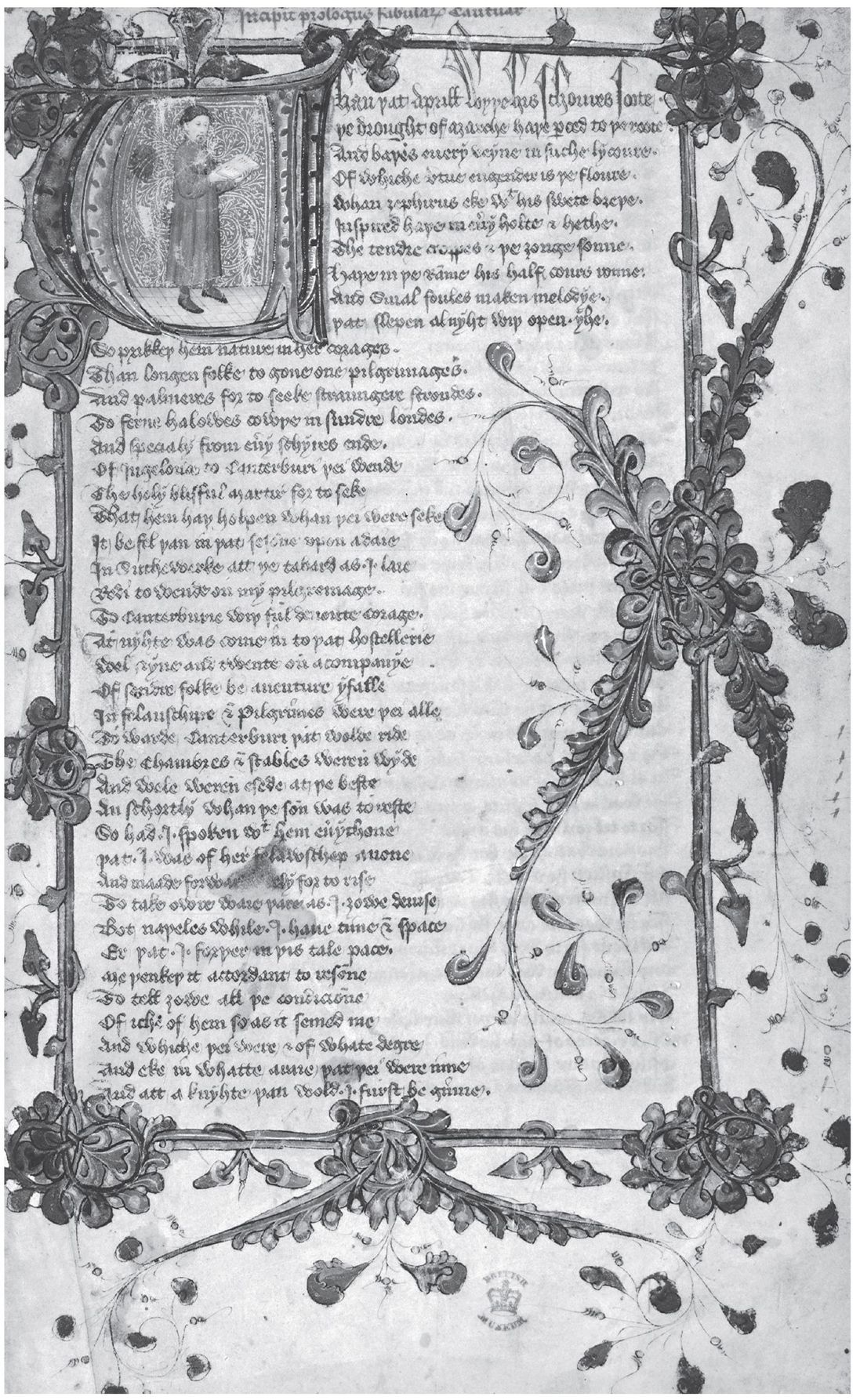

14. Geoffrey Chaucer's

The Canterbury Tales

was written in English. This page of the Prologue, from a manuscript of c. 1420, portrays the author himself (

top left

).

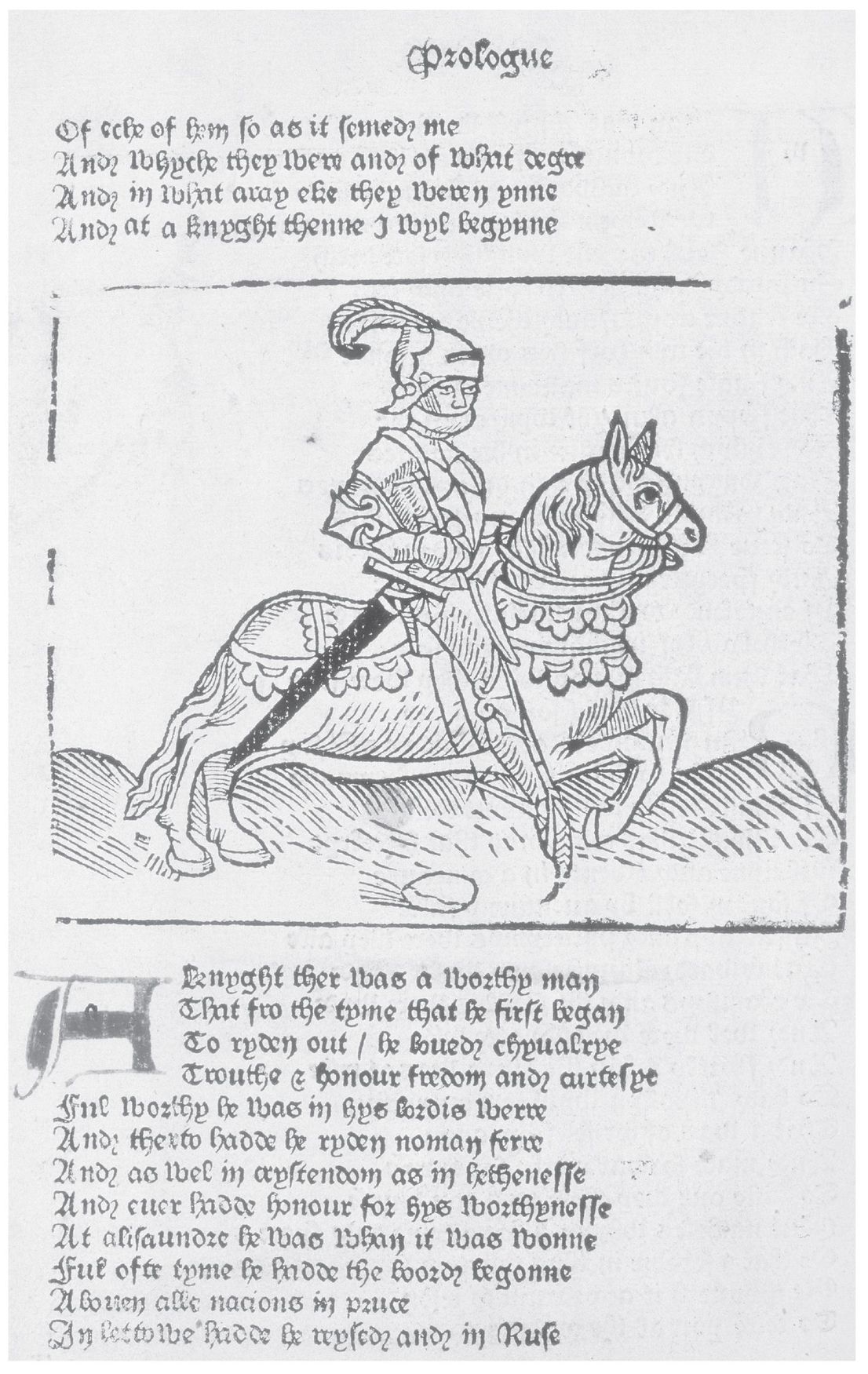

15. Prologue to

The Canterbury Tales,

from the printed version by Caxton c. 1485. Before the end of the fifteenth century Caxton had printed two editions and

The Canterbury Tales

has never been out of print in English since.

16. John Wycliffe inspired two biblical translations that bear his name. His followers, known as Lollards, preached against the Church's wealth and corruption. He was condemned as a heretic, his body exhumed and burned and the ashes thrown into the River Swift, a tributary of the Avon.