The Adventure of English (11 page)

Read The Adventure of English Online

Authors: Melvyn Bragg

Here are the opening lines, first in Wycliffe's English and then in modern speech:

In the bigynnyng God made of nouyt heuene and erthe. Forsothe the erthe was idel and voide, and derknessis weren on the face of depthe; and the Spiryt of the Lord was borun on the watris. And God seide, Liyt be maad, and liyt was maad. And God seiy the liyt, that it was good, and he departide the liyt fro derknessis; and he clepide the liyt, dai, and the derknessis, nyyt. And the euentid and morwetid was maad, o daie.

In the beginning, God made of naught heaven and earth. Forsooth, the earth was idle and void, and darkness were on the face of depth, and the spirit of God was borne on the waters. And God said “Light be made!” â and light was made. And God saw the light that it was good and He departed the light from the darkness. And he klept the light day and the darkness night. And the eventide and morrowtide was made, one day.

That passage is straightforward. But in many places it is not an easy translation. Yet many familiar phrases do have their English origin in this translation: “woe is me,” “an eye for an eye” are both in Wycliffe, as are words such as “birthday,” “canopy,” “child-bearing,” “cock-crowing,” “communication,” “crime,” “to dishonour,” “envy,” “frying-pan,” “godly,” “graven,” “humanity,” “injury,” “jubilee,” “lecher,” “madness,” “menstruate,” “middleman,” “mountainous,” “novelty,” “Philistine,” “pollute” â “puberty,” “schism,” “to tramp,” “unfaithful” and “zeal” â all these and many more were read first in Wycliffe's Bible. Once again we see not only additions to the English word-hoard but new ideas being introduced or current ideas being given a name â “humanity,” “pollute” â which then, as words often do, took on a larger and more complex life. New words are new worlds. You call them up and if they are strong enough, they keep in step with change and along the way describe more and more, provide new insights, evolve on the tongue and on the page. How many nuances and therefore meanings attach to the multiple uses of the world “humanity”? In the cause of bringing his greatly revered faith to the English, Wycliffe not only widened the ecclesiastical vocabulary â “graven,” “Philistine,” “schism” â he also let loose words which over the next four centuries would net meanings far removed from the perilously translated texts of medieval Oxford.

The criticism of Wycliffe's Bible is that it is too Latinate. So in awe were they of the authority of the Latin version that they translated word for word, even keeping the Latin word order, as in “Lord, go from me for I am a man sinner” and “I forsoothe am the Lord thy God full jealous.” Another result was that the text itself is shot through with Latinate words, some directly imported, some of which came through the French, such as “mandement,” “descrive,” “cratch.” There are over one thousand Latin words that turn up for the first time in English whose use in England is first recorded in Wycliffe's Bible, words such as “profession,” “multitude” and “glory” â a good word for this Bible.

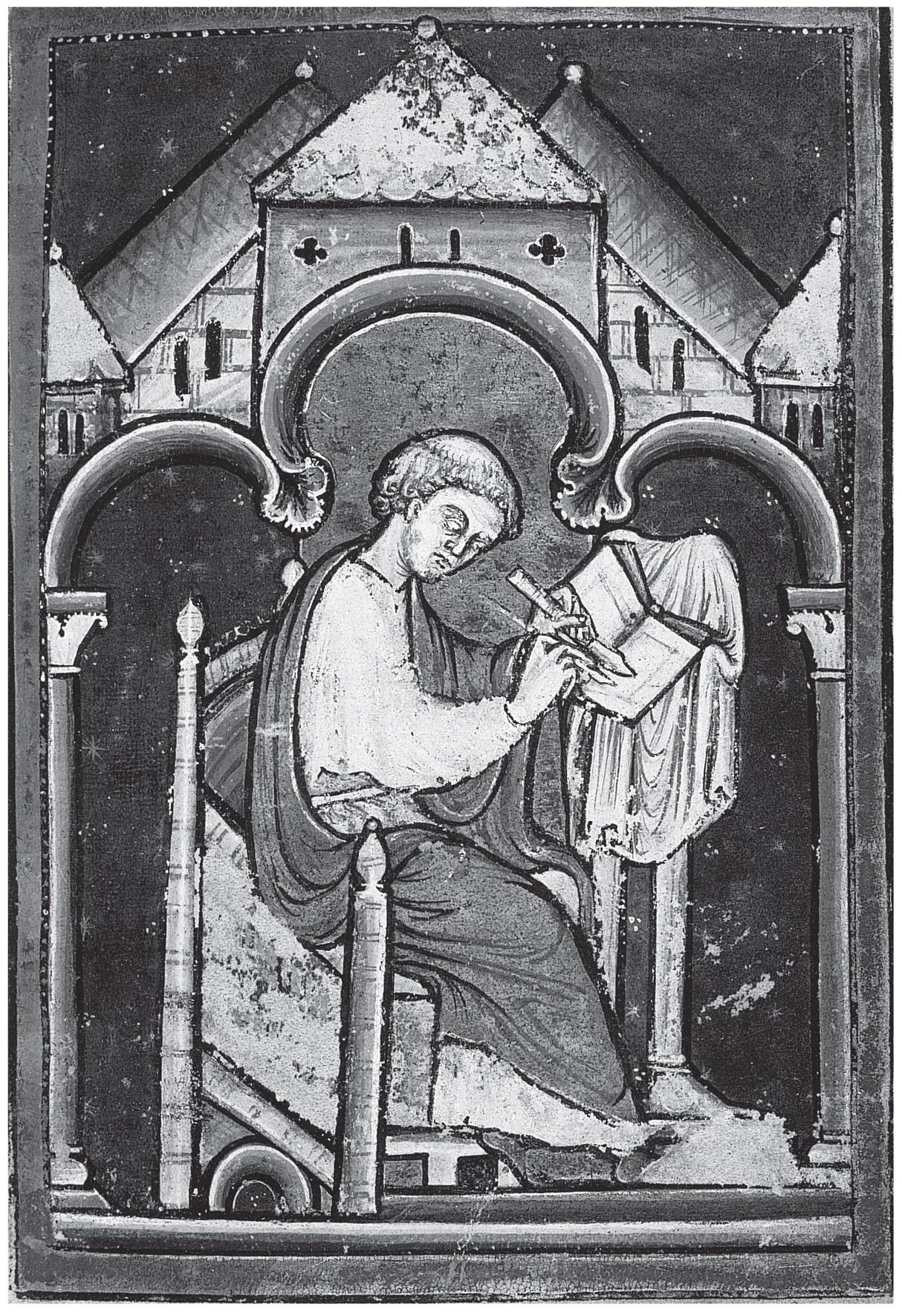

1. Bede, English monk and scholar, wrote the first ever history of the English-speaking people in Latin, completed in 731. He proposed that the English language should also be used in books.

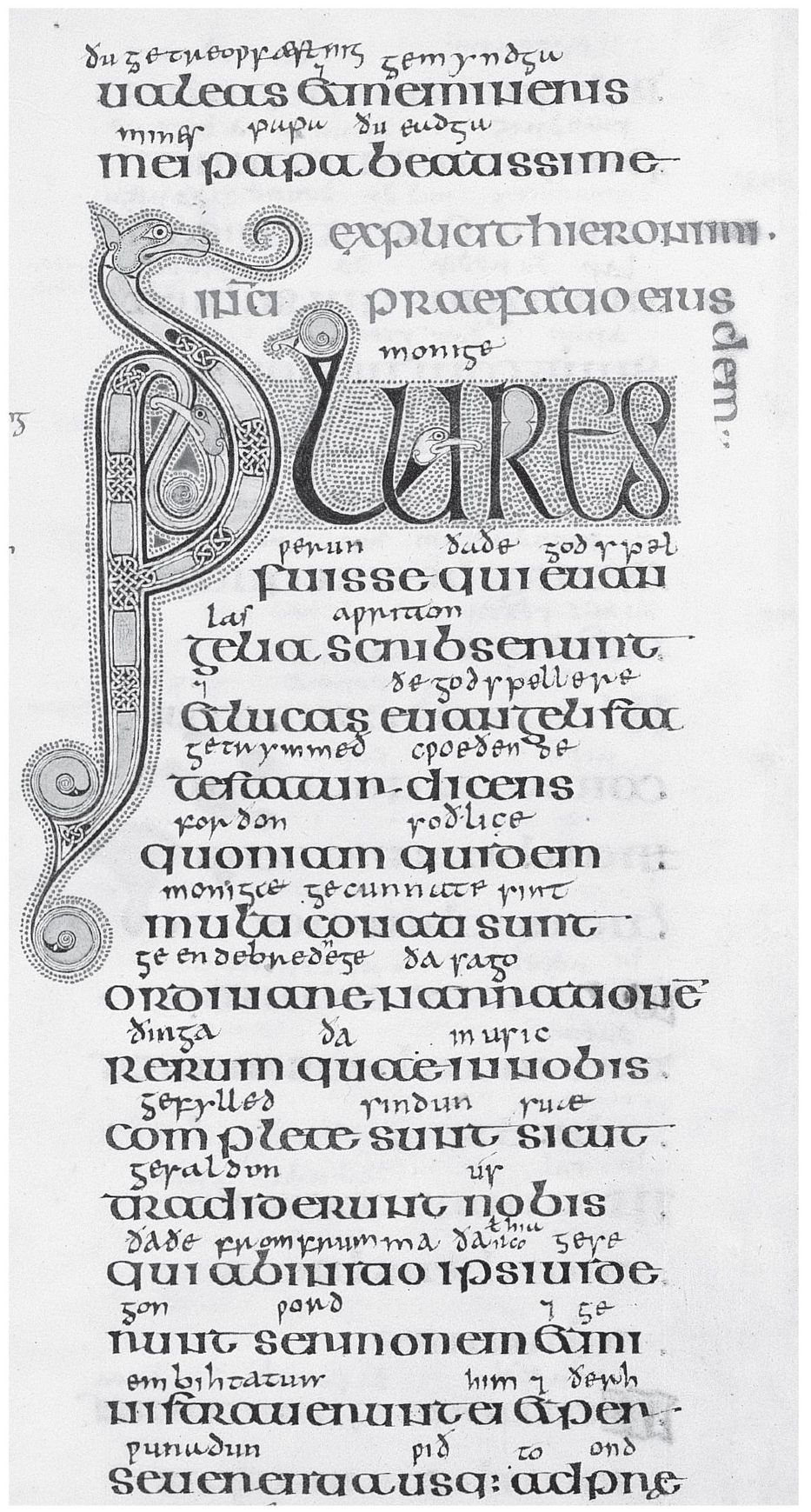

2. St. Jerome's Preface from the Lindisfarne Gospels, late seventh century. Aldred's tenth-century “gloss” is a word-for-word English translation of the Latin.

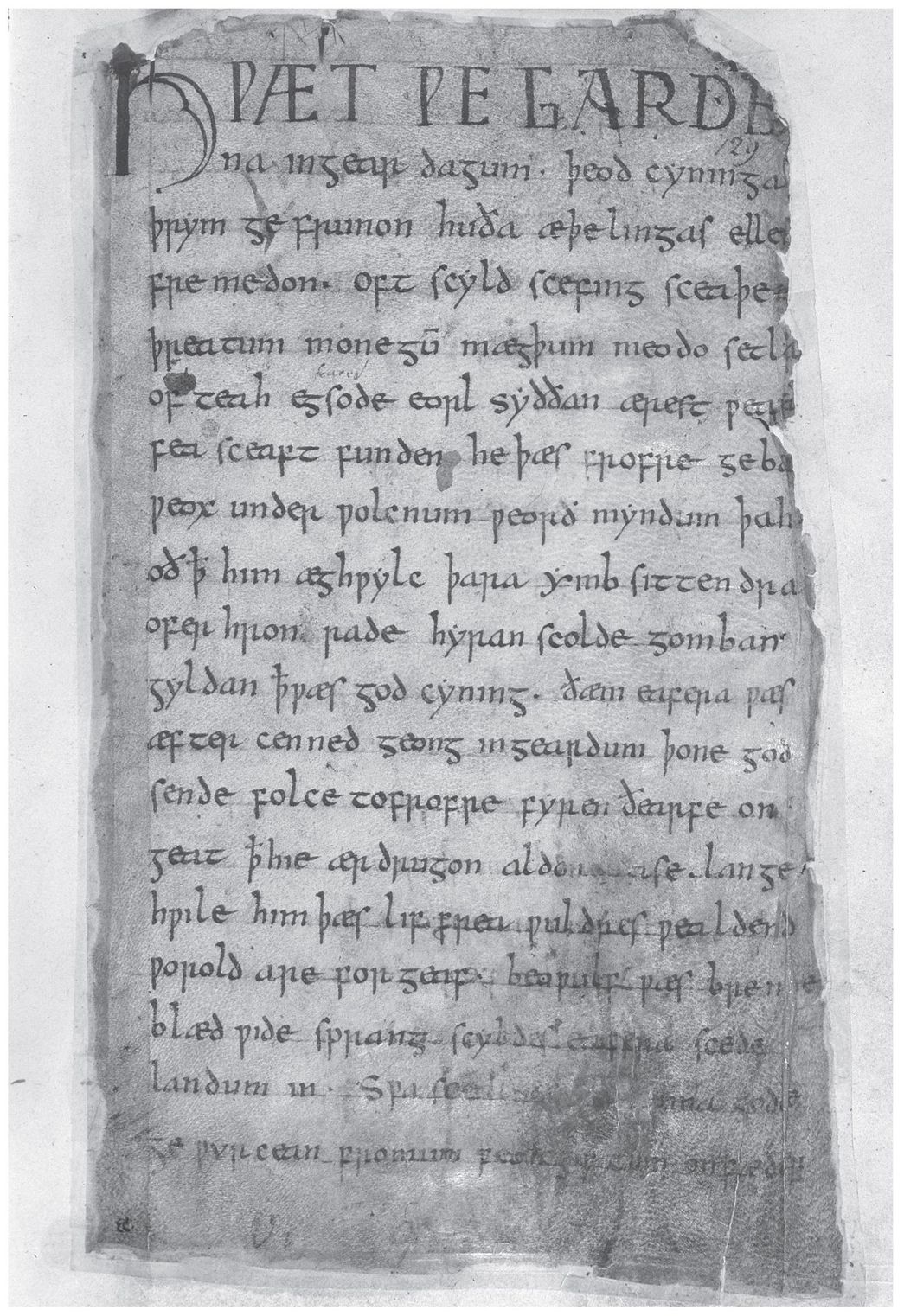

3. The only surviving manuscript of

Beowulf,

dating from the tenth century, the first great poem in the English language, begins, “So: the Spear Danes in days gone by / And the Kings who ruled their clan were a legend . . .”

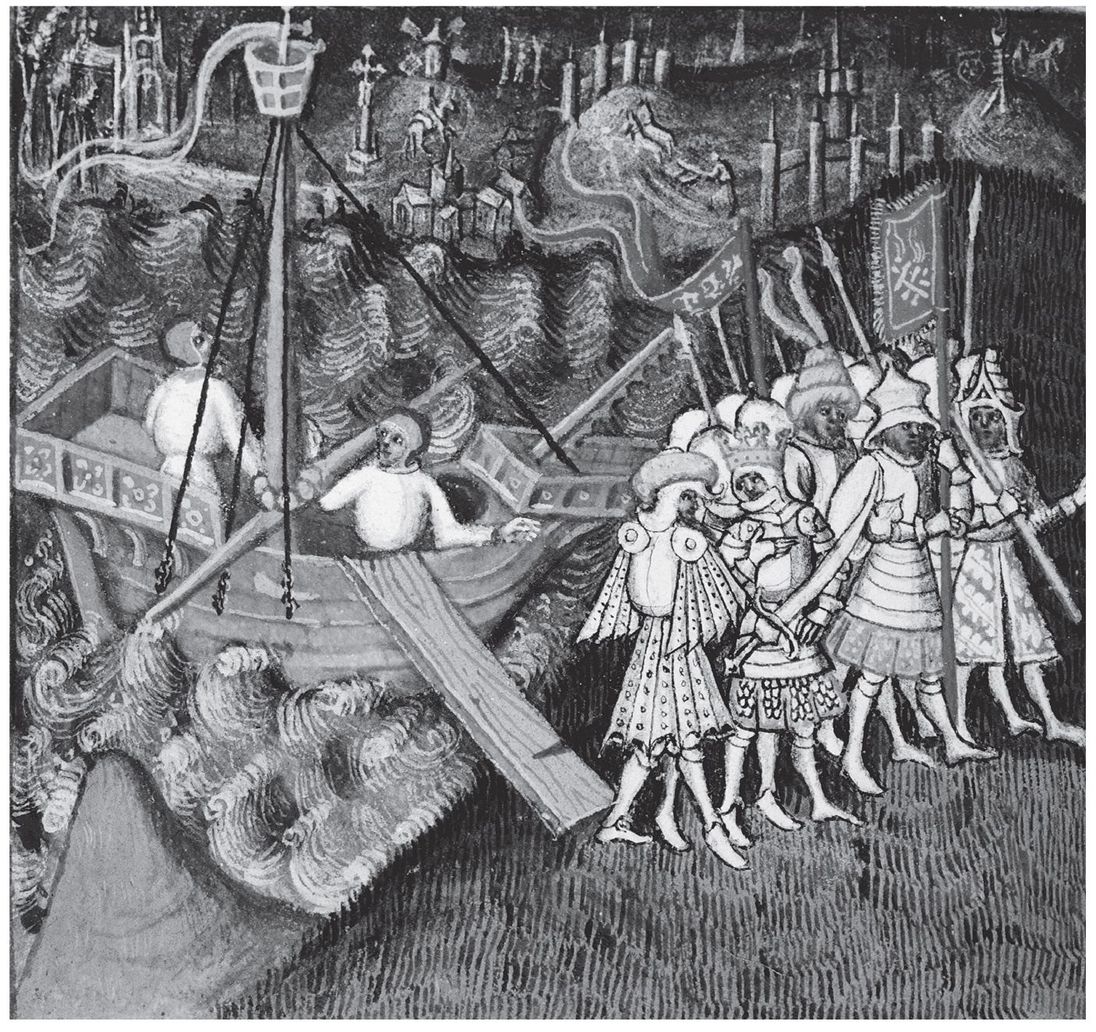

4. By the mid-ninth century the marauding Danes threatened to take over the English language.

5. The Alfred jewel bears the inscription â in English â “Alfred had me made.” By defeating the Danes, Alfred had saved the English language.

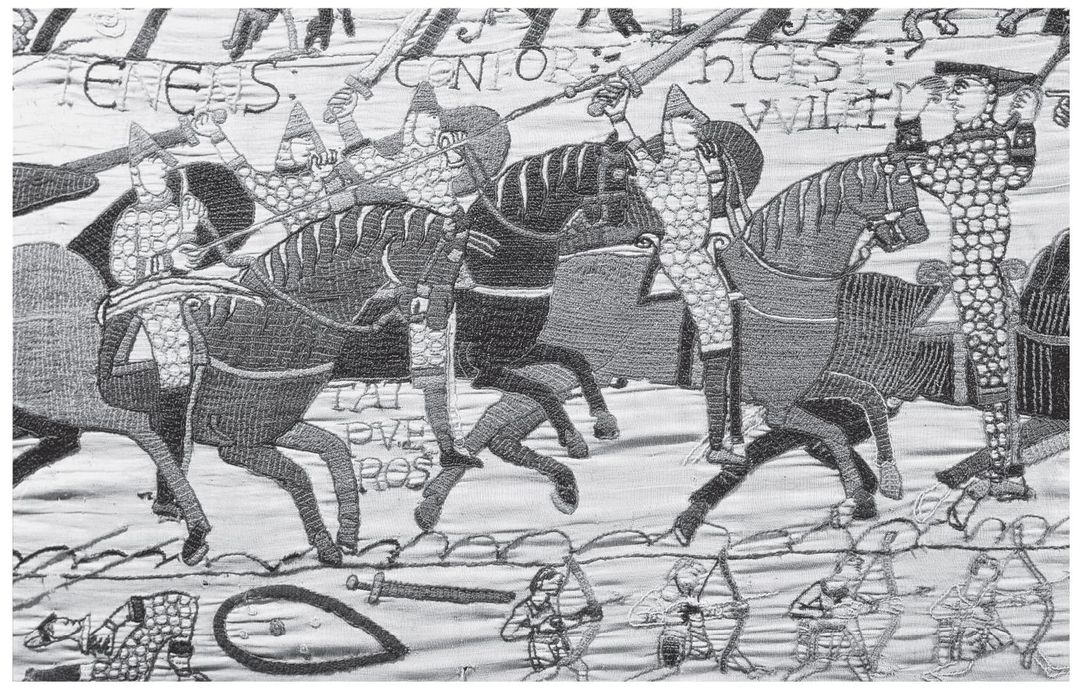

6. After William's victory at Hastings in 1066, depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, the French language of power and authority ruled the land.

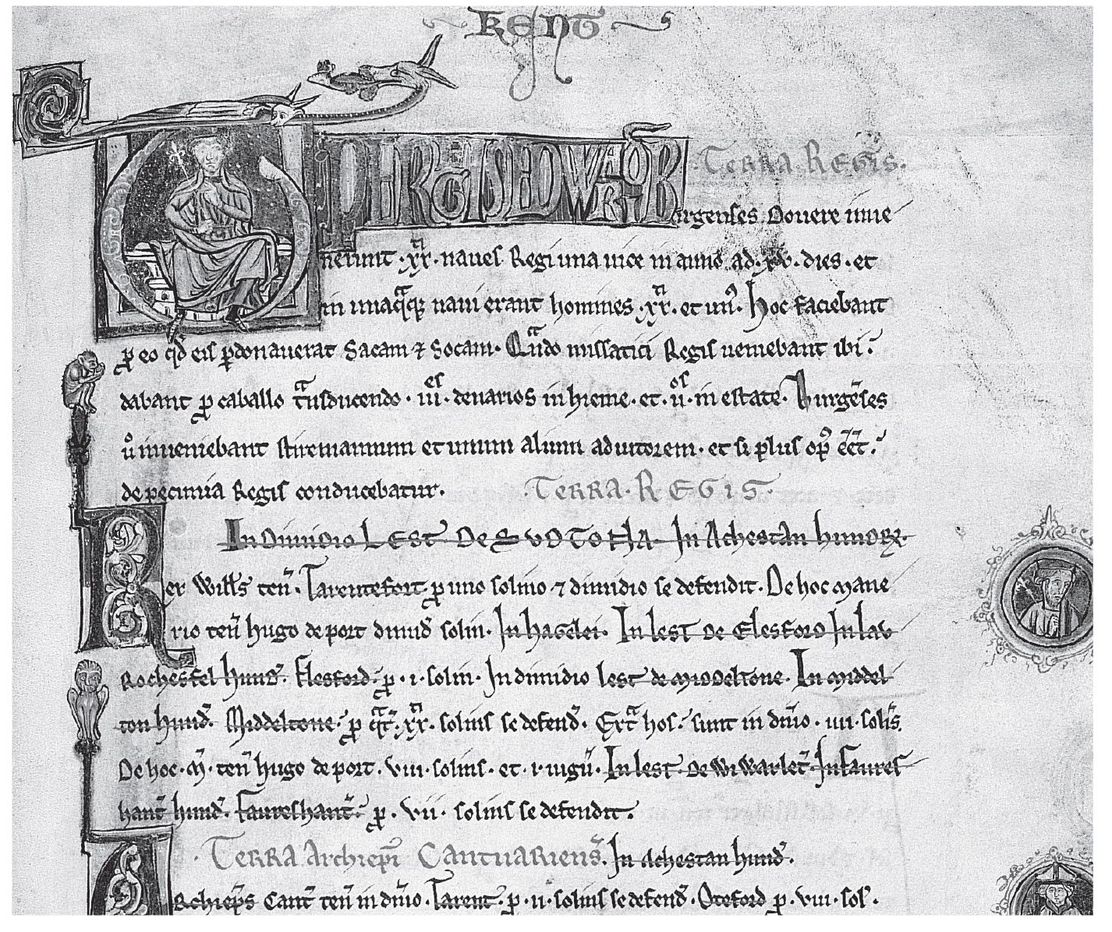

7. Twenty years later, William sent out his officers to take stock of his kingdom. The result, the Domesday Book, was written in Latin. Detail from the shorter illustrated version.

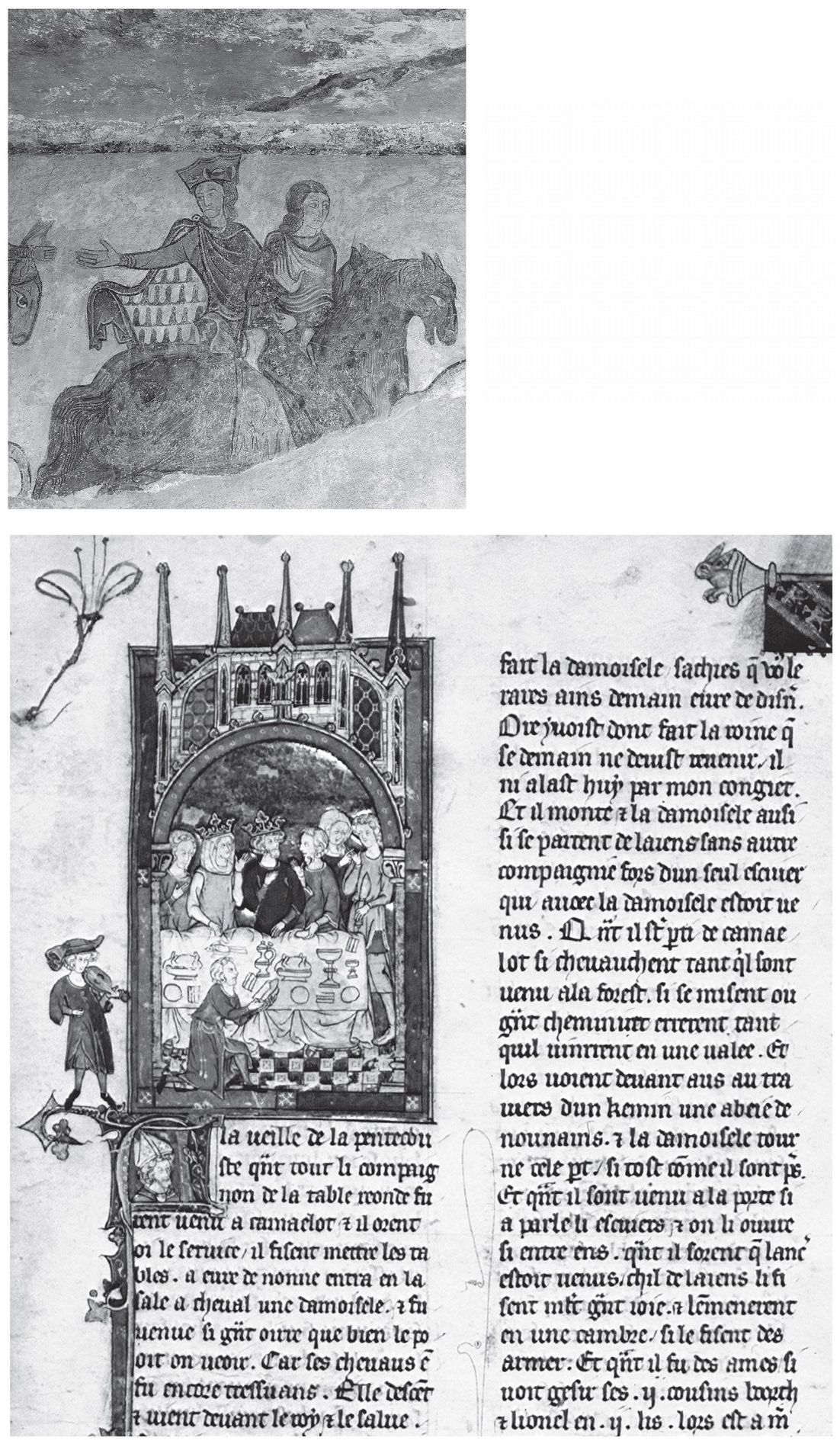

8 and 9. Henry II with his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine â their reign saw a growing poetic tradition, embodied in Arthurian romance. This French manuscript (

below

) shows King Arthur and Guinevere with Lancelot kneeling before them.

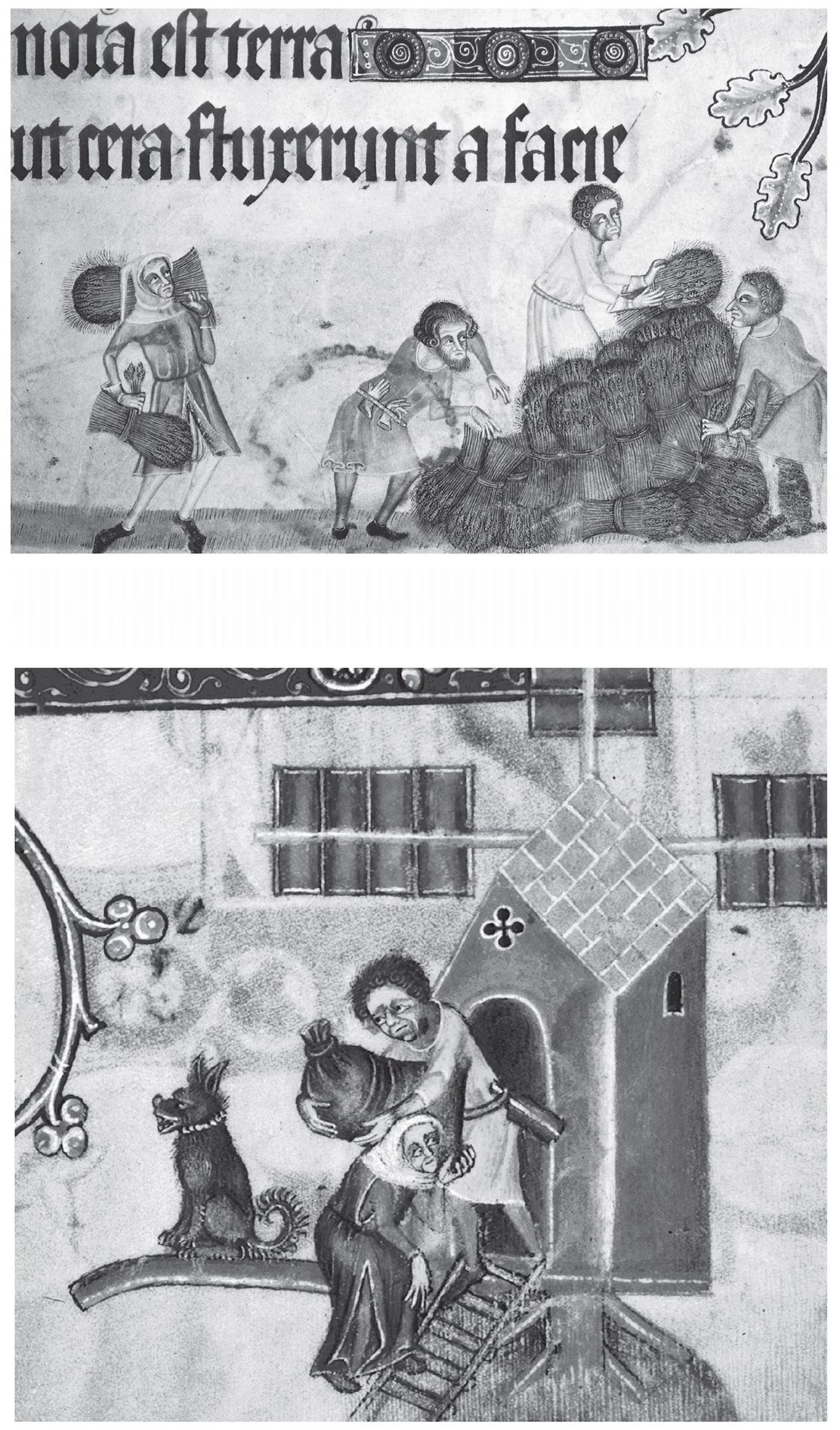

10. Scenes from the early fourteenth-century Luttrell Psalter: while the French-speaking court feasted, the English-speaking labourers tended the land.

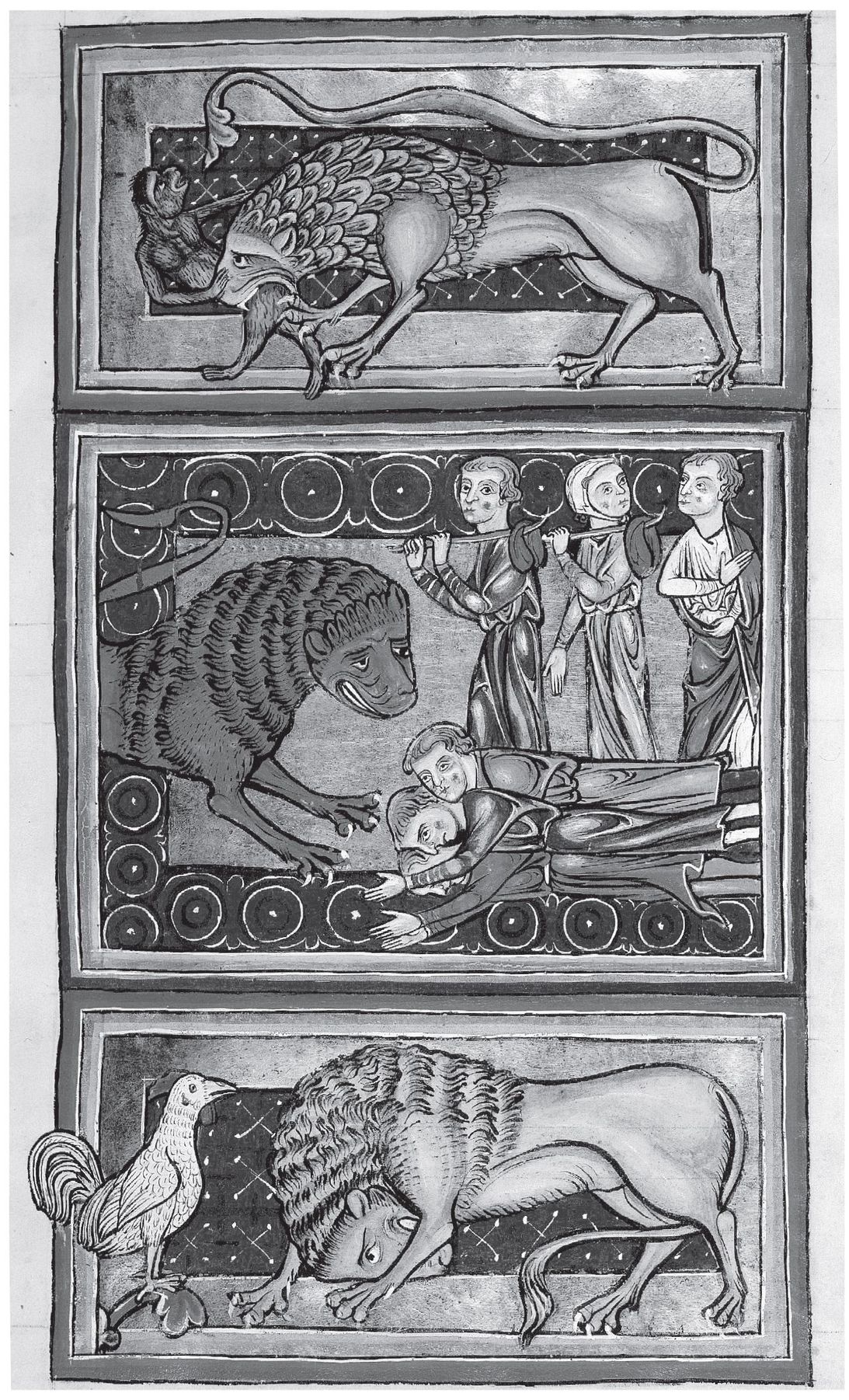

11. Bestiaries were usually written in Latin but by the late thirteenth century a few were being elaborated and translated into English.