The 30 Day MBA (25 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

The birth of viral marketing, using the power of Metcalf's Law to the full, has been attributed to the founder of Hotmail, who insisted that every e-mail sent by a Hotmail user should incorporate the message âGet your free web-based e-mail at Hotmail'. By clicking on this line of text, the recipient would be transported to the Hotmail home page. While this e-mail sent by the company itself would not have had much effect, at the foot of an e-mail sent by a business colleague or friend it made a powerful impact. The very act of sending a Hotmail message constituted an endorsement of the product and so the current customer was selling to future customers on the company's behalf just by communicating with them.

- Structural options

- Line and staff relationships

- Building and leading teams

- Understanding motivation

- Managing people effectively

- Directors' roles

- Handling change

O

rganizational behaviour, usually shortened to OB, is the whole rather amorphous area that deals with people, why they behave the way they do and how to create and manage an organization that can achieve the goals set for the business. As one cynical CEO summarized the task: âto get people to do what I want them to do because they want to do it'.

The single most prevalent reason for a strategy failing lies in its implementation; the analysis and planning behind a proposed course of action are rarely the root of the problem. That is more likely to lie in the selection of the people to implement strategy, their management, motivation, rewards and the way in which they are organized and led. Stated like that, it sounds a fairly simple task. Just work your way through those headings and any MBA worth their salt should be able to get the desired results. Unfortunately, people both individually and collectively are rarely malleable and infinitely variable in their likely responses to situations. The famous German military strategist Moltke's statement that âNo campaign plan survives first contact with the enemy' applies here if the word enemy is replaced by organization.

However, by understanding and applying a number of principles and concepts on the typical MBA syllabus you can improve an organization's chances of achieving its objectives.

Strategy vs structure, people and systems

This is the âwhich came first' question akin to that of the chicken and the egg. Unless you are starting up an organization on a greenfield site with no people other than yourself and only a pile of cash, every business situation involves some compromise between the ideal and the possible when it comes to people and structures.

The theory is clear. An organization's strategy, itself a product of its business environment, determines the shape of the organization's structure, the sort of people it will employ and how they will be managed, controlled and rewarded. But in the real world the business environment is constantly changing as the economy fluctuates, competitors come and go, and consumer needs, desires and aspirations alter. In any event a business is limited in its freedom of action. However violent and essential a change in strategy, a business will rarely be free to hire and fire staff at will simply to change direction. The exception is in the case of a complete closure or withdrawal from an activity such as that of Marks & Spencer's controversial closure of its French outlets in 2001. This move was considered vital to the survival of the whole business and despite May Day protests in France the company's shares rose 7 per cent on the announcement.

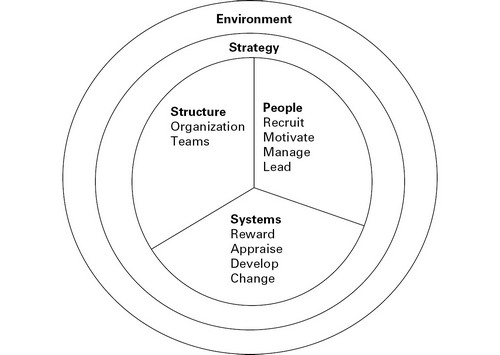

Figure 4.1

is a useful aid to understanding how to approach OB. The concentric circles are a metaphor to remind us of the circular nature of subject. You can't just tackle one area without having an impact on others.

FIGURE 4.1

Â

A framework for understanding organizational behaviour

Just as the skeleton is the structure that holds a body together, a business too has its framework. The goal of any framework is to provide some boundaries while at the same time allowing the whole âbody' flexibility to respond in order to go about its business. While human bodies keep a very similar skeleton to the one they start out with, a business has a number of very different organizational structures to choose from. Also, it is unlikely that any one structure will be appropriate throughout an organization's life.

For an organization a structure has to perform the following functions:

- show who is responsible for what and to whom;

- define roles and responsibilities;

- establish communication and control mechanisms;

- lay out the ground rules for cooperation between all parts of the organization;

- set out the hierarchy of authority, power and decision making.

There are two major building blocks used in shaping an organization's structure beyond the level of the individual: the organizational chart and team composition.

Pictorial methods of describing how organizations work have been around for centuries. Both the Roman and Prussian armies had descriptions of their hierarchical structures and the latter incorporated line and staff relationships. There is also some evidence that the ancient Egyptians documented their methods for organizing and dividing workers on major projects such as the pyramids. However, Daniel C McCallum is generally credited with developing the first systematic set of organizational charts in 1855, to organize railroad building on an efficient basis. The trigger for his innovation was the discovery that the building costs per mile of track did not drop with the length of line being built, contrary to logic. The inefficiencies were being caused by poor organization.

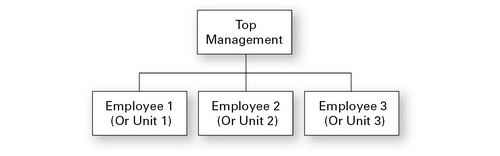

Basic hierarchical organization

This simple structure has every member or part of the organization reporting in to one person (

Figure 4.2

). It works well when the organization is small, decisions are simple or routine and communications are easy.

FIGURE 4.2

Â

Basic hierarchical organization chart

This basic structure can be based around one of several groupings, including:

- functions such as marketing or manufacturing;

- geography such as country or region;

- product;

- customer or market segment such as trade, consumers, new accounts or key accounts.

Span of control

The number of people a manager can have reporting to them in a hierarchy is governed by the span of control. Few people reporting and the span of control is termed as narrow, and more as wide.

A narrow span of control means that any one manager has fewer people reporting to them, so communications should be better and control easier. However, as the organization grows, that usually means creating more and more layers of management, so negating any earlier efficiency.

A wide span of control, also known as a flat management structure, involves having many people or units reporting to one person. This usually means having fewer layers of management, but it does call for a greater level of skill from those doing the managing. The nature of the tasks being carried out by subordinates will limit the capacity to run a flat organization. For example, a regional manager responsible for identical units such as branches of a supermarket chain, supported by good and well-developed control systems, may be able to have 10 or more direct reports. But if the organization comprises very different types of unit, for example retail outlets, central bakeries, garages, factories, accounts departments and sales teams, the ability of any one manager to handle that diversity will be limited.

A further factor to take into account is the skill level of both managers and managed. A higher-skilled workforce can operate with a wider span of control as they will need less supervision and a higher-skilled manager can control a greater number of staff.

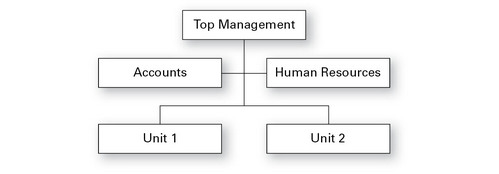

Line and staff organization

One way to keep an organization structure flat as the enterprise gets bigger and more complex is to introduce staff functions that take over some of the common duties of unit managers. For example, a production manager could probably handle their own recruitment, selection and training of staff while they have a dozen or so people in their domain. Once that expands to hundreds, and if growth is also impacting on other management areas such

as sales and marketing, then it may be more efficient to create a specialist HR unit to support the line managers.

Staff positions support line managers by providing knowledge and expertise but the buck ultimately stops with the line manager. Three types of authority are created in a line and staff organization, so alongside some efficiencies lies the possibility for conflict:

- Line authority goes down the chain of command, giving those further up the right and responsibility to instruct those below them to carry out specific tasks.

- Staff authority is the right and responsibility to advise line managers in certain areas. For example, an HR staffer will advise a line manager on redundancy terms, conditions of employment and disciplinary issues.

- Functional authority or limited line authority gives a staff person the ultimate sanction over particular functions such as safety or financial reporting.

There are possibilities for conflict in the relationship between line and staff but these can be minimized in two ways. In the first instance staff report to their own superiors who have line authority over them. Second, line and staff personnel can be organized into teams with shared goals and objectives (

Figure 4.3

).

FIGURE 4.3

Â

Line and staff organization chart

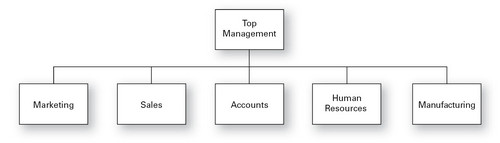

Functional organization

In a functional organization (

Figure 4.4

) the staff and line managers all report to a common senior manager. This places more of a burden on senior management who have a wider span of control and a greater variety of tasks for which to take responsibility. However, this structure concentrates all responsibility in one person and so minimizes the area for conflict. It may also deny an organization the high level of expertise that comes with having a professional staff function. For example, this would leave the onus for being fully conversant with current employment law on a production manager, rather than giving them access to staff advice. They can, of course, read up on the law themselves, but that is not quite as good as having it as a part of an everyday skill and experience base.

FIGURE 4.4

Â

Functional organization chart

Matrix organization

A matrix organization gives two people line authority for interlocking areas of responsibility. In

Figure 4.5

you can see that a manager is responsible for sales of product group 1 in both Europe and Asia. However, a manager is also responsible for the sales of all product groups within their continent.