The 12th Planet (55 page)

Authors: Zecharia Sitchin

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Gnostic Dementia, #Fringe Science, #Retail, #Archaeology, #Ancient Aliens, #History

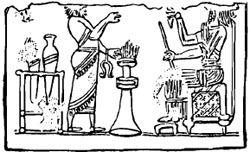

Fig. 150

Sumerian texts, too, speak of deformed humans created by Enki and the Mother Goddess (Nin

h

ursag) in the course of their efforts to fashion a perfect Primitive Worker. One text reports that Nin

h

ursag, whose task it was to "bind upon the mixture the mold of the gods," got drunk and "called over to Enki,"

"How good or how bad is Man's body?

As my heart prompts me,

I can make its fate good or bad."

Mischievously, then, according to this text—but probably unavoidably, as part of a trial-and-error process—Nin

h

ursag produced a Man who could not hold back his urine, a woman who could not bear children, a being who had neither male nor female organs. All in all, six deformed or deficient humans were brought forth by Nin

h

ursag. Enki was held responsible for the imperfect creation of a man with diseased eyes, trembling hands, a sick liver, a failing heart; a second one with sicknesses attendant upon old age; and so on.

But finally the perfect Man was achieved—the one Enki named Adapa; the Bible, Adam; our scholars,

Homo sapiens.

This being was so much akin to the gods that one text even went so far as to point out that the Mother Goddess gave to her creature, Man, "a skin as the skin of a god"—a smooth, hairless body, quite different from that of the shaggy ape-man.

With this final product, the Nefilim were genetically compatible with the daughters of Man and able to marry them and have children by them. But such compatibility could exist only if Man had developed from the same "seed of life" as the Nefilim. This, indeed, is what the ancient texts attest to.

Man, in the Mesopotamian concept, as in the biblical one, was made of a mixture of a godly element—a god's blood or its "essence"—and the "clay" of Earth. Indeed, the very term

lulu

for "Man," while conveying the sense of "primitive," literally meant "one who has been mixed." Called upon to fashion a man, the Mother Goddess "Washed her hands, pinched off clay, mixed it in the steppe." (It is fascinating to note here the sanitary precautions taken by the goddess. She "washed her hands." We encounter such clinical measures and procedures in other creation texts as well.)

The use of earthly "clay" mixed with divine "blood" to create the prototype of Man is firmly established by the Mesopotamian texts. One, relating how Enki was called upon to "bring to pass some great work of Wisdom"—of scientific know-how—states that Enki saw no great problem in fulfilling the task of "fashioning servants for the gods." "It can be done!" he announced. He then gave these instructions to the Mother Goddess:

"Mix to a core the clay

from the Basement of Earth,

just above the Abzu—

and shape it into the form of a core.

I shall provide good, knowing young gods

who will bring that clay to the right condition."

The second chapter of Genesis offers this technical version:

And Yahweh, Elohim, fashioned the Adam

of the clay of the soil;

and He blew in his nostrils the breath of life,

and the Adam turned into a living Soul.

The Hebrew term commonly translated as "soul" is

nephesh,

that elusive "spirit" that animates a living creature and seemingly abandons it when it dies. By no coincidence, the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Old Testament) repeatedly exhorted against the shedding of human blood and the eating of animal blood "because the blood is the

nephesh."

The biblical versions of the creation of Man thus equate

nephesh

("spirit," "soul") and blood.

The Old Testament offers another clue to the role of blood in Man's creation. The term

adama

(after which the name Adam was coined) originally meant not just any earth or soil, but specifically dark-red soil. Like the parallel Akkadian word

adamatu

("dark-red earth"), the Hebrew term

adama

and the Hebrew name for the color red

(adom)

stem from the words for blood:

adamu, dam.

When the Book of Genesis termed the being created by God "the Adam," it employed a favorite Sumerian linguistic play of double meanings. "The Adam" could mean "the one of the earth" (Earthling), "the one made of the dark-red soil," and "the one made of blood."

The same relationship between the essential element of living creatures and blood exists in Mesopotamian accounts of Man's creation. The hospital-like house where Ea and the Mother Goddess went to bring Man forth was called the House of Shimti; most scholars translate this as "the house where fates are determined." But the term

Shimti

clearly stems from the Sumerian SHI.IM.TI, which, taken syllable by syllable, means "breath-wind-life."

Bit Shimti

meant, literally, "the house where the wind of life is breathed in." This is virtually identical to the biblical statement.

Indeed, the Akkadian word employed in Mesopotamia to translate the Sumerian SHI.IM.TI was

napishtu

—

the

exact parallel of the biblical term

nephesh.

And the

nephesh

or

napishtu

was an elusive "something" in the blood.

While the Old Testament offered only meager clues, Mesopotamian texts were quite explicit on the subject. Not only do they state that blood was required for the mixture of which Man was fashioned; they specified that it had to be the blood of a god, divine blood.

When the gods decided to create Man, their leader announced: "Blood will I amass, bring bones into being." Suggesting that the blood be taken from a specific god, "Let primitives be fashioned after his pattern," Ea said. Selecting the god,

Out of his blood they fashioned Mankind;

imposed on it the service, let free the gods....

It was a work beyond comprehension.

According to the epic tale "When gods as men," the gods then called the Birth Goddess (the Mother Goddess, Nin

h

ursag) and asked her to perform the task:

While the Birth Goddess is present,

Let the Birth Goddess fashion offspring.

While the Mother of the Gods is present,

Let the Birth Goddess fashion a

Lulu;

Let the worker carry the toil of the gods.

Let her create a

Lulu Amelu,

Let him bear the yoke.

In a parallel Old Babylonian text named "Creation of Man by the Mother Goddess," the gods call upon "The Midwife of the gods, the Knowing Mami" and tell her:

Thou art the mother-womb,

The one who Mankind can create.

Create then

Lulu,

let him bear the yoke!

At this point, the text "When gods as men" and parallel texts turn to a detailed description of the actual creation of Man. Accepting the "job," the goddess (here named NIN.TI—"lady who gives life") spelled out some requirements, including some chemicals ("bitumens of the Abzu"), to be used for "purification," and "the clay of the Abzu."

Whatever these materials were, Ea had no problem understanding the requirements; accepting, he said:

"I will prepare a purifying bath.

Let one god be bled....

From his flesh and blood,

let Ninti mix the clay."

To shape a man from the mixed clay, some feminine assistance, some pregnancy or childbearing aspects were also needed. Enki offered the services of his own spouse:

Ninki, my goddess-spouse,

will be the one for labor.

Seven goddesses-of-birth

will be near, to assist.

Following the mixing of the "blood" and "clay," the childbearing phase would complete the bestowal of a divine "imprint" on the creature.

The new-born's fate thou shalt pronounce;

Ninki would fix upon it the image of the gods;

And what it will be is "Man."

Depictions on Assyrian seals may well have been intended as illustrations for these texts—showing how the Mother Goddess (her symbol was the cutter of the umbilical cord) and Ea (whose original symbol was the crescent) were preparing the mixtures, reciting the incantations, urging each other to proceed. (Figs. 151, 152)

the cutter of the umbilical cord) and Ea (whose original symbol was the crescent) were preparing the mixtures, reciting the incantations, urging each other to proceed. (Figs. 151, 152)

The involvement of Enki's spouse, Ninki in the creation of the first successful specimen of Man reminds us of the tale of Adapa, which we discussed in an earlier chapter:

In those days, in those years,

The Wise One of Eridu, Ea,

created him as a model of men.

Scholars have surmised that references to Adapa as a "son" of Ea implied that the god loved this human so much that he adopted him. But in the same text Anu refers to Adapa as "the human offspring of Enki." It appears that the involvement of Enki's spouse in the process of creating Adapa, the "model Adam," did create some genealogical relationship between the new Man and his god: It was Ninki who was pregnant with Adapa!

Fig. 151