Teutonic Knights (6 page)

Authors: William Urban

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Medieval, #Germany, #Baltic States

The Transylvanian Experiment

As happens often in human affairs, it was chance that led the Teutonic Knights to consider making a change in their life’s mission. A common acquaintance introduced Hermann von Salza to the king of Hungary, and within a short time the grand master committed his order to its first great venture in Eastern Europe. The central figure in this affair was Count Hermann of Thuringia, the overlord of the Salza family. The Salzas had been loyal vassals who had probably named Hermann in honour of their powerful patron, who was famous for his brilliant court, where he encouraged poetry and chivalry. The count’s ancestors were noted crusaders – his father had been on the Third Crusade and he himself had been present when the Teutonic Order was transformed from a hospital order into a military one. It is quite possible that Hermann von Salza had accompanied him on that crusade and had joined the Teutonic Knights at that time. Certainly Count Hermann had followed Hermann von Salza’s career with much interest. At the time that the news would have found its way back to the Thuringian court that Hermann von Salza had been elected master of the Teutonic Order, Count Hermann was negotiating with Andrew II of Hungary (1205 – 35) to win the hand of four-year-old Princess Elisabeth for his son Louis. The king had long contemplated a crusade to the Holy Land, a subject that fascinated him and Count Hermann alike, but he could not leave Hungary while it was endangered by the increasingly strong attacks of the pagan Cumans.

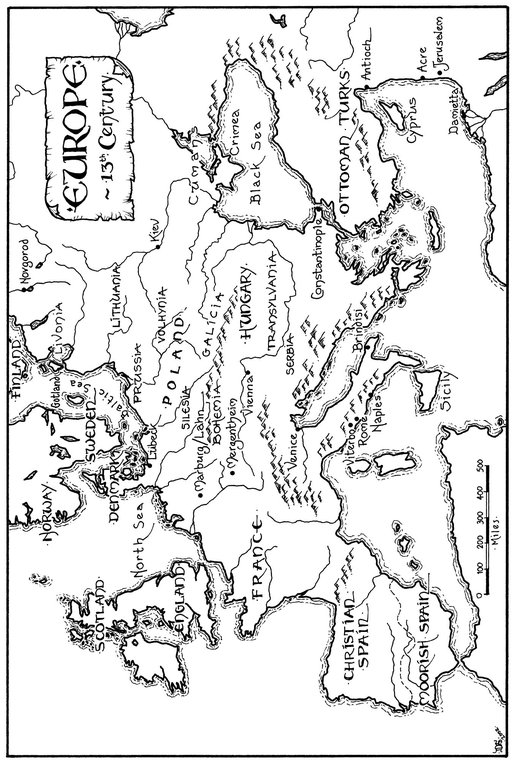

The Hungarian kingdom extended over the vast plain that lay south of the Carpathian mountains and stretched across the Danube River to the hills that bounded the kingdom of Serbia. In its south-eastern part the steep mountain chain became less formidable and dissolved into rolling, forested hill country variously called Transylvania or Siebenbürgen (seven fortresses). This wild region was never fully settled by the Hungarians, who were themselves descendants of nomads and therefore preferred the plain, and it was but sparsely populated by the descendants of the Roman settlers of Dacia. The passes served less for commerce than to lead the Cumans from the coastal plain into Hungary. King Andrew had tried to stem the invasions by planting vassals in the region, but these either lacked a sufficient number of warriors to hold the land securely or preferred a safe and easy life in the interior. When Andrew mentioned this problem to Count Hermann or his emissaries, he was most likely told that a military order such as the Teutonic Knights could protect this endangered frontier, making it possible for the king to go on crusade with a free mind. Although there were other ways that Andrew could have heard of Hermann von Salza and his order – his queen was from the Tyrol, an early base of the order – it seems more than a coincidence that the king invited the Teutonic Knights to come to Transylvania only shortly after signing the marriage contract with Hermann of Thuringia.

The king promised lands in the endangered region and immunities from taxes and duties; this implied that the military order could bring in settlers and maintain itself from their rents and labour without having to share its hard-won early revenues with the monarch. In effect, Andrew was presenting them that part of Transylvania called the Burzenland. He kept the right to coin money and a claim to half of any gold or silver that might be discovered, but he renounced his claims to taxes and tolls, and his authority to establish markets and exercise justice. This appeared to be a generous offer, and because the officers of the military order had little experience in such affairs, Hermann von Salza accepted the invitation on the assumption that the king’s goodwill would continue into the future.

Almost immediately a contingent of knights, accompanied by peasant volunteers from Germany, entered the unsettled region and built a series of wood-and-earth forts; the peasants then established their farms and villages, providing the taxes and labour necessary to support these military outposts. Such settlements by religious orders were very common in this era, and the ethnic origin of the peasants generally meant little to the nobles and clerics who profited from their presence. The peasants soon began to harvest reasonably abundant crops, making it easy to attract yet more immigrant farmers from Germany. Only after these tasks had been accomplished did it become apparent that the king’s offer was terribly vague and unspecific. By that time, however, little could be done to change it, because he was absent on the Fifth Crusade.

Andrew had sailed to the Holy Land in 1217 with a large army, accompanied by Hermann von Salza and a force of Teutonic Knights. Finding the crusaders in Cyprus idle, without much hope of mounting an offensive toward Jerusalem, the king and Hermann von Salza had called all the crusader leaders together and proposed to attack Egypt. If they could capture Cairo, which seemed weakly defended, they could exchange that city for Jerusalem and the surrounding fortresses. First, however, they had to capture Damietta. When that siege did not succeed as quickly as hoped, King Andrew returned home overland, making a truce with the Turks in Asia Minor to permit him safe-passage back to Hungary.

Meanwhile, the contingent of Teutonic Knights in Transylvania had not been content to act the part of quiet vassals, defending the frontier in a static manner. They were ambitious and aggressive, pressing outward against the Cumans, and they found it easy to occupy new territories, because the nomads had no permanent settlements that might provide centres of resistance. By 1220 the Teutonic Knights had built five castles, some in stone, and given them names that were later passed on to castles in Prussia. Marienburg, Schwarzenburg, Rosenau, and Kreuzburg were grouped around Kronstadt at a distance of twenty miles from one another. These became bases for expansion into the practically unpopulated Cuman lands, an expansion that went forward with such surprising speed that the Hungarian nobles and clergy who previously had shown little interest in the region became jealous and suspicious.

If the Teutonic Knights had been given another decade, they would probably have pushed down the Danube River valley to occupy all the territories down to the Black Sea; this would have relieved the pressure that the nomadic Cumans had long exerted on Hungary and the Latin kingdom of Constantinople. Garrisoning castles in the lower Danubian basin, they could have reopened the land route to Constantinople that had been unsafe for crusaders in recent decades. But the Teutonic Knights were too successful too quickly. The Hungarian nobles began to have doubts that the Cumans were still a danger. They could remember that those wild horsemen had beaten the Byzantines and the Latin king of Constantinople, and had even invaded their own country. But that was in the past. Now it seemed that even a handful of foreign knights could drive them away. The Hungarian nobles did not understand the special organisation and dedication that made it possible for a military order to succeed where they had failed. For their part, the Teutonic Knights ignored the rights of the local bishop and refused to share their conquests with important nobles who had previously held claims on the region.

It was only natural that the Teutonic Knights did not wish to surrender what had been won or built by their efforts and with their money, particularly when they would need every parcel of land and every village to provide the resources in food, taxes, and infantry necessary for future campaigns toward the Black Sea. But in addition their leaders may not have possessed the diplomatic skills of Hermann von Salza, who knew how to make friends and allay the suspicions of potential enemies; moreover, being far away in the Holy Land and Egypt, Hermann was not even in a position to offer advice. Consequently the Teutonic Knights in Transylvania operated with considerable autonomy, and they did not make many friends.

The result was a conflict of ambitions and bitter jealousy. As the Hungarian nobles came to see it, King Andrew had unwisely invited in a group of interlopers who were making themselves so secure in their border principality that the king himself would soon not be able to control them. They accused the order of overstepping its duty to defend the border and of planning to become a kingdom within the kingdom.

Even if Hermann von Salza had not been at Damietta, it is unlikely that he could have done much about these developments. If the pope was unable to persuade distant and quarrelsome nobles to support the crusading movement, what chance did a minor noble in charge of a minor military order have?

Andrew returned home to a kingdom bitter about the losses and expenses of his crusade. His reputation had diminished badly, and the country had suffered in the absence of firm government. In 1222 the nobility extorted from him a document called the Golden Bull, which was very similar to the

Magna Carta

that English barons had extorted from their own unlucky king only a few years before. Even so, when the nobility demanded that he take back his grants to the Teutonic Order, he refused. He examined the complaints, concluded that the order had indeed exceeded its mandate, and agreed that changes should be made in the charters; but he ended by issuing a new charter more extensive in its terms than the first. He allowed the Teutonic Knights to build castles in stone; and, although his grant forbade them to recruit Hungarian or Romanian settlers, he implicitly approved their having brought in German peasants. Hermann von Salza had doubtless used his influence with Pope Honorius III (1216 – 27) and Count Louis of Thuringia to strengthen the royal resolve on this issue, but he could not affect the attitude of the Hungarian nobility; nor could he win over the heir apparent, Prince Bela, who had thrown in his lot with them. These continued their complaints against the Teutonic Order and supported the local bishop in his ambition to subordinate the order to his rule.

Hermann von Salza reasoned that his order need not anticipate trouble as long as King Andrew was alive, but that he could expect great difficulties once Prince Bela mounted the throne. This could be avoided, perhaps, if the order could loosen its ties to the crown. When he returned to Italy he spoke to Honorius III about the problem, and subsequently the pope took the order’s lands in Transylvania under papal protection. In effect, the Burzenland became a fief of the Holy See.

This action was a fatal mistake. In place of trouble at some future date, Hermann von Salza had to deal with it at once. Andrew ordered the Teutonic Knights to leave Hungary immediately. Not even he was willing to see a valuable province lost, stolen from his kingdom by legal chicanery. The pope intervened as best he could, and Hermann von Salza tried to explain that the act had been misinterpreted, but it was of no use. The Hungarian nobles had their issue, and now the king stood with them. When the Teutonic Knights unwisely refused to leave without a further hearing, Prince Bela was authorised to lead an armed force against them. The order was driven ignominiously from its lands and expelled from the kingdom. Only the peasantry remained, forming an important German settlement until 1945, when their descendants were expelled by the Rumanian government.

The Hungarians did not replace the Teutonic Order with adequate garrisons or follow up on the attacks on the Cumans, thereby enabling the steppe warriors to recover their self-confidence and their strength. Soon the Cumans were again a danger to the kingdom.

The Hungarian debacle shook the confidence of the Teutonic Order badly. Many men had given their lives, and much money had been collected with great difficulty to build the fortifications and make the new settlements secure. These efforts were all wasted. The order’s reputation was besmirched. In the recent past many gifts had come from the emperor and the princes – estates in Bari, Palermo and Prague. How many potential donors would consider the stories they heard and then make their donations elsewhere? The answer was not at all certain, although the example of the Tyrolean count of Lengmoos was encouraging – in the midst of the controversy he had joined the order and brought all his lands with him as a gift. Such a knight, reared in the art of the Alpine plateau where German chivalry and poetry flourished a short way from rich and vibrant Italian cities, was a living example of the problem the Teutonic Order faced. It could thrive in Germanic regions, winning recruits and donations from idealistic nobles and burghers, but it had no reason to operate in those areas. To have a purpose for existence the Teutonic Knights had to fight infidels or pagans, and those could be found only on the borders of non-German states. Unfortunately, the nobles and people of those states often had little in common with the members of the Teutonic Order; therefore, hostility rather than sympathy was their natural attitude toward the crusaders once the immediate danger had passed.