Teutonic Knights (34 page)

Authors: William Urban

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Medieval, #Germany, #Baltic States

The propagandists of the order worked hard to persuade contemporaries that the disaster was not as bad as it appeared, that it was the work of the devil through his agents, the pagans and schismatics – and most of all, that it was the fault of

the Saracens

. Moreover, they argued that now more than ever crusaders were needed in Prussia to continue God’s work. The Polish propagandists laboured, too, to present their interpretation of events, but they did not have the long-term contacts which had been developed in many crusading

Reisen

. Their praise of Jagiełło and his knights tended to awaken more sympathy for the hard-pressed order than was good for Polish interests. After the first impact of the news was absorbed by the European courts, after the first months of difficulty had passed, interpretations favoured by the order tended to prevail.

The modern reader, looking back on almost six centuries of events that dwarf the battle of Tannenberg without driving it from the public mind, hardly knows how to understand the negative attitudes toward the Teutonic Knights. Comparisons to Wilhelmine Germany of 1914 and to Hitler are unworthy of comment, though Germans of those generations thought of their acts as deeds of national revenge for the battle in 1410. In the context of twentieth-century events one is tempted to say that contemporaries of Tannenberg were right, that there is a divine justice operating in the world. In concluding that the Teutonic Knights had paid the price for having lived by the sword and swaggered in a world of pride, contemporaries found that Biblical admonitions came easily to mind: Tannenberg was God’s punishment for the Teutonic Order’s outrageous conduct. Pride had risen too high – Jungingen personified his order’s universally acknowledged tendency to arrogance and anger – and a fall had to follow.

The deficiencies of this method of justifying past events (

Weltgeschichte als Weltgericht

) should be obvious: if victory in battle reflects God’s will, then the Tatar domination of the steppe and the harassment of Polish and Lithuanian borderlands is also a reflection of divine justice; God punishes kings by sacrificing many thousands of innocent lives. Good Old Testament theology, but hard to fit into a New Testament framework. It is best that we do not tarry long in either the shadowy realm of pop psychology or dark religious nationalism, but move back into the somewhat better-lit world of chronicles and correspondence.

Conflicting views of modern historians about the battle of Tannenberg and its aftermath make for interesting if confused reading. One could summarise them roughly by saying that until the 1960s each interpretation reflected national interests more than fact. Since then, historians have become both more polite and less certain of their inability to err. Archaeology is beginning to shed light on the battlefield, giving promise that problems left by the literary sources may be more fully resolved. Political issues in Germany and Poland that seemed to depend on every imaginable historical justification have disappeared with the political parties that sponsored them, so that at last a quiet discussion about the past is possible. Most importantly, since the fall of Communism German and Polish historians have come to respect each other sufficiently to give real attention to one another’s ideas. There is, indeed, reason to hope that some day we may come to a better and more general agreement as to what really happened at Tannenberg and what it really signified.

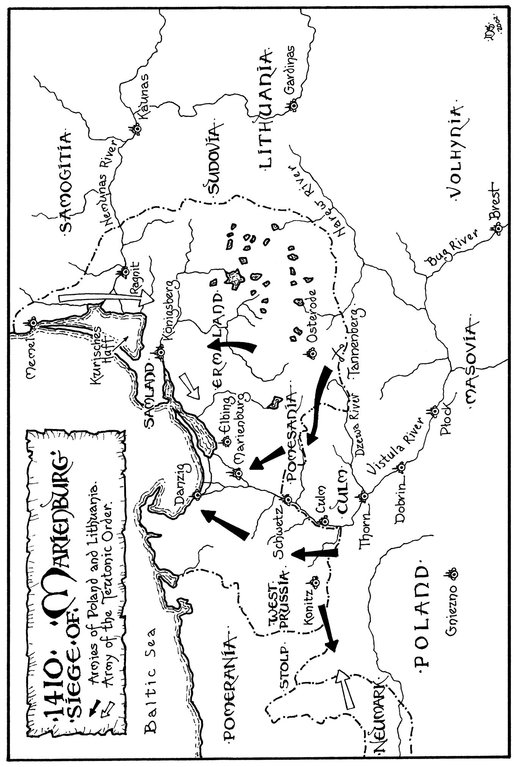

The Long Decline and the End in the Baltic

When Jagiełło’s forces had rested three days from the exhaustion of battle and the pursuit, he ordered them to move north. There was no hurry. The king was never one to rush. Still, he did not allow himself to be diverted by opportunities to occupy towns and castles that could be easily taken, but headed straight for Marienburg at a deliberate pace. If Jagiełło could make himself master of that great fortress, he would be well placed to occupy the rest of Prussia. Already secular knights and burghers were coming to him, declaring their willingness to live as Polish subjects if their former rights and privileges were guaranteed. Garrisons of castles, often not having orders to fight or sufficient men to defend the walls, were surrendering; castellans who urged resistance, as at Osterode, Christburg, Elbing, Thorn, and Culm, were expelled by burghers who then surrendered the cities. There seemed no point in resisting the inevitable. Even the bishops of Ermland, Culm, Pomesania, and Samland hurried to Jagiełło to acknowledge him as their lord. Lesser men, overcome by the depressing spirit of defeatism, followed their example. Jagiełło’s chancery was hard-pressed to issue documents defining each new vassal’s rights and obligations.

The king sent his men out to find the body of Ulrich von Jungingen and take it to Osterode for burial; later the fallen grand master’s corpse was brought to Marienburg to lie with his predecessors in St Anne’s Chapel.

Jagiełło and Vytautas were enjoying a triumph of which they had hardly dared dream. Their grandfather had once claimed the Alle River – which more or less marked the boundary between the settled lands along the coast and the wilderness to the south-east – as the Lithuanian frontier. Vytautas now seemed to be in a position to claim all the lands east of the Vistula. Jagiełło was ready to make good the ancient Polish claims to Culm and West Prussia. However, even as they were celebrating their brief moment of joy there appeared among the Teutonic Knights the only member of this generation whose leadership and tenacity could be compared to theirs: Heinrich von Plauen. Nothing in his past had indicated that Plauen would ever be more than a simple castellan, but he was one of those men who rise suddenly above themselves in moments of crisis. Born forty years earlier in the Vogtland, a small territory between Thuringia and Saxony, he had first come to Prussia as a crusader. Impressed by the warrior-monks, he had taken the vows of poverty, chastity, obedience, and war against the enemies of the Church. His noble birth had guaranteed him a position of rank, and long service had earned him promotion to command at the castle of Schwetz, a well-manned observation post on the west bank of the Vistula north of Culm for the defence of the West Prussian frontier against raiders.

When Plauen learned of the magnitude of the order’s defeat, he alone of all the surviving castellans assumed responsibility beyond what had been assigned to him: he ordered his 3,000 troops to Marienburg, to garrison the fortress there before the Polish army could arrive. Nothing else mattered. If Jagiełło wished to divert his efforts to Schwetz and capture it, so be it. Plauen’s duty, as he saw it, was to save Prussia. That meant defending Marienburg, not worrying about minor castles.

All Plauen’s training and experience ran against this assumption of authority. The Teutonic Knights prided themselves in their unconditional obedience, and it was not immediately clear whether or not a more prominent officer had escaped the battlefield. However, in this situation obedience was a principle that cut with the flat side of the sword: it had turned out officers who did not exceed instructions without long reflection; no one made independent decisions. In the Teutonic Order one rarely had to hurry; there was time to discuss matters fully, to consult a council or an assembly of commanders, and to come to a common understanding. Even the most self-assured grand masters consulted the membership about military decisions. Now there was no time for that, and the traditions of the military order paralysed all the surviving officers save one; the rest were awaiting orders or seeking an opportunity to talk with others about formulating a plan of action.

Heinrich von Plauen began to give orders: to commanders of threatened castles, ‘Resist!’; to Danzig sailors, ‘Come to Marienburg!’; to the Livonian master, ‘Send troops as quickly as possible!’; to the German master, ‘Raise mercenary troops and send them east!’ Such was the Prussian tradition of obedience that his orders were carried out. A miracle that should not have occurred did. Resistance stiffened everywhere; when the first Polish scouts arrived at Marienburg, they found defenders lining the walls, ready to fight.

Plauen gathered men from every possible place. He had the small garrison of Marienburg, his own men from Schwetz, the ‘ships’ children’ from Danzig, some secular knights, and the militia of Marienburg. That the last was ready to assist is witness to Plauen’s personality: among his first commands was one to burn the city and suburbs to the ground. This act of destruction prevented the Poles and Lithuanians from finding shelter and stores, eliminated demands that Plauen attempt to defend the city walls, and cleared the ground in front of the castle. It was perhaps more important morally in indicating how far the commander was ready to go to save the castle.

The surviving knights, their secular brethren, and the burghers began to stir out of their shock. After the first Polish scouts withdrew, Plauen’s men stocked the castle’s larders with bread, cheese, and beer, drove pigs and cattle inside the walls, and hauled fodder from the storehouses and fields. They brought guns into position, removed remaining obstructions to a clear field of fire, and discussed plans for defending the fortress against all possible attacks. When the main units of the royal army arrived on 25 July, the garrison had already gathered in supplies for a siege of eight to ten weeks. That was food and fodder the Poles and Lithuanians themselves needed.

Vital to the defence of the fortress was Heinrich von Plauen’s spirit. His genius for improvisation, his desire for victory, together with an insatiable lust for revenge, spread to the garrison. Those character traits had probably prevented his advancement earlier – a volatile temperament and impatience with incompetence are not appreciated in a peacetime army. At this critical moment, however, they were exactly the qualities that were needed.

He wrote to Germany:

To all princes, barons, knights and men-at-arms and all other loyal Christians, whomever this letter reaches. We brother Heinrich von Plauen, castellan of Schwetz, acting in the place of the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order in Prussia, notify you that the King of Poland and Duke Vytautas with a great force and with Saracen infidels have besieged Marienburg. In this siege truly all the Order’s forces and power are being engaged. Therefore, we ask you illustrious and noble lords, to allow your subjects who wish to assist and defend us for the love of Christ and all of Christendom either for salvation or money, to come to our aid as quickly as possible so that we can drive them away.

Plauen’s call for help against the ‘Saracens’ may have been hyperbolic (though some Tatars were Moslems), but it touched a nerve of anti-Polish sentiment and stirred the German master into action. Knights began moving toward the Neumark, where the former advocate of Samogitia, Michael Küchmeister, still had a considerable force intact, and officers hurriedly sent out notices that the Teutonic Order was willing to hire any mercenary who would report for duty immediately.

Jagiełło had hoped that Marienburg would capitulate quickly. Demoralised troops elsewhere were surrendering at the least threat. Those at Marienburg, he persuaded himself, would surely do the same. However, when the garrison, unexpectedly, did not capitulate, the king had only unsatisfactory alternatives to choose from. He was unwilling to attempt an assault on the high walls, and retreat would be an admission of defeat. So he ordered his army to begin siege operations in the hope that the defenders would lose hope; the combination of fear of death and hope of surviving was a powerful inducement to surrender on terms. However, Jagiełło quickly learned that he did not have sufficient troops to press an attack on a fortress as large and well designed as Marienburg and simultaneously send troops to other cities to demand their surrender; nor had he ordered his own siege guns sent down the Vistula in time to use them now. The longer his forces remained before Marienburg, the more time the Teutonic Knights had to organise their defences elsewhere. The royal victor cannot be blamed greatly for his miscalculation (what would historians have said if he had not tried for the jugular vein?), but his siege tactics failed. Polish troops hammered away at the walls for eight weeks with catapults and cannon taken from nearby castles. Lithuanian foragers burned and ravaged the countryside, sparing only those regions where the burghers and nobles hastened to provide them with cannons and powder, food and drink. Tatar raiders struck throughout Prussia, proving to everyone’s satisfaction that their reputation for savagery was well deserved. Polish forces moved into West Prussia, capturing many small castles which had been left without garrisons: Schwetz, Mewe, Dirschau, Tuchel, Bütow, and Konitz. But the vital centres of Prussia, Königsberg and Marienburg, remained untouched. Dysentery broke out among the Lithuanian forces (too much delicate food), and finally Vytautas announced that he was taking his men home. However, Jagiełło was determined to remain until he had taken the castle and captured its commander. He refused offers of a truce, demanding the prior surrender of Marienburg. He was sure that just a little more perseverance would be sufficient for total victory.

Meanwhile, help had started on its way to Prussia. The Livonian army came to Königsberg, relieving troops there for use elsewhere. This helped counter accusations about ‘the Livonian treason’, for having honoured the truce with Vytautas rather than having harassed his lands and forced him to divert troops to frontier defence. From the west, Hungarian and German mercenaries hurried to the Neumark, where they were formed into an army by Michael Küchmeister. This officer had been inactive till now, too concerned about the loyalty of the nobility to risk an engagement against Polish forces, but in August he ordered his small army against an equal number of Poles, routed them, and captured the opposing commander. Then he marched east, recapturing city after city. By the end of September Küchmeister had cleared West Prussia of hostile forces.

At that point Jagiełło was unable to maintain the siege any longer. Marienburg was impregnable if the garrison did not lose its nerve; and Plauen saw to it that the hastily assembled troops retained their will to fight. Moreover, the garrison was encouraged by the withdrawal of the Lithuanian forces and the news of victories elsewhere. Therefore, even though supplies were dwindling, they took heart in the good news and in the knowledge that the order’s Hanseatic allies controlled the rivers. In the meantime, Jagiełło’s knights were pressing him to go home – the time that they were required to render military service had long since expired. He was running out of supplies, and disease had broken out among his troops. In the end, Jagiełło had no choice but to acknowledge that the defence still had a great advantage over the offence; a brick fortress surrounded by water defences could be taken only after a lengthy siege, and perhaps even then only when luck or treason tipped the odds. Jagiełło did not have the time or the resources for a longer siege at this juncture, and he would not have them in the future.

After eight weeks, on 19 September the king gave the command to withdraw. He had built a stronghold at Stuhm, just south of Marienburg, fortifying it strongly, garrisoning it with his best men, and then filling it with all the food and fodder that could be collected from the countryside. Afterward he ordered his men to burn all the fields and barns in the vicinity to make it more difficult for the Teutonic Knights to collect food for a siege. By holding a fortress in the heart of Prussia, he hoped to keep the pressure on his enemies and to give encouragement and protection to the nobles and burghers who had surrendered to him. On his way home he stopped at the shrine of St Dorothea in Marienwerder to pray. Jagiełło was now at all times a devout Christian. In addition to personal piety, which he wanted no one to doubt because of his pagan and Orthodox past, he had to demonstrate that surrounding himself with Orthodox and Moslem troops was purely business.

As the Polish forces retreated, history repeated itself. Almost two centuries before, as Prussia was conquered by armies of crusaders from Poland and Germany, it was the Poles who did much of the fighting, but the Teutonic Knights who eventually came into possession of the lands because, then as now, there were too few Polish knights willing to stay in Prussia and defend it for the king. The Teutonic Knights had the greater endurance. In the same manner they now survived the disaster at Tannenberg.

Plauen gave orders to pursue the retreating army. The Livonian forces moved first, besieging Elbing and compelling the citizens to surrender, then moving south into Culm and regaining most of the cities there. The castellan of Ragnit, whose troops had been watching Samogitia during the battle of Tannenberg, moved through central Prussia to Osterode, capturing the castles one by one and expelling the last of the Poles from the order’s territories. By the end of October Plauen had recovered every town except Thorn, Nessau, Rehden, and Strasburg – all located right on the border. Even Stuhm had surrendered after three weeks, the garrison abandoning their castle in return for free passage to Poland with all their possessions. The worst was over. Plauen had saved his order in its most desperate moment. His courage and determination had sparked a similar commitment from others, and he had turned the broken survivors of a military disaster from beaten men into warriors. He did not believe that one battle would be decisive for the history of his organisation, and he inspired many to share his vision of ultimate victory.

Aid from the West came surprisingly quickly as well. Sigismund declared war on Jagiełło and sent more troops to the border of southern Poland to pin down knights who might join Jagiełło’s army. Sigismund wanted the Teutonic Knights to remain a threat to Poland’s northern provinces and be able to aid him in the future; it was in this spirit that he had earlier agreed with Ulrich von Jungingen that neither would make peace without consulting the other. Ambitious to become emperor, he wanted to present himself to German princes as a firm defender of German institutions and German lands. Therefore, exceeding any legitimate authority – as was appropriate for a true leader in crisis situations – he called the electors together in Frankfurt am Main and urged them to send help to Prussia immediately. Most of this was show, however. Sigismund’s real interest was in being elected German king, the first step to becoming emperor.