Teutonic Knights (32 page)

Authors: William Urban

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Medieval, #Germany, #Baltic States

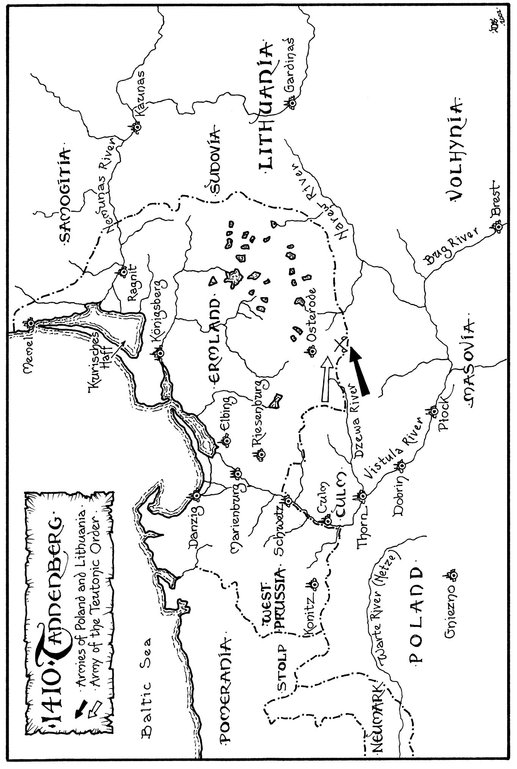

The armies began to gather. When ready, Jagiełło summoned Vytautas to join him in Masovia. Until recently that had required a journey through a dense, swampy wilderness. However, thanks to the opening of the trade route along the Narew River it was now possible for Vytautas to bring his men to the desired location near Płock without undue difficulties. The bulk of the royal forces remained on the western bank of the Vistula, but Jagiełło sent Polish knights to the other bank to hold the fords for Vytautas, and more troops were coming in daily. By mid-June the king had at his disposal a force of more than 30,000 cavalry and infantry (18,000 Polish knights and squires, with a few thousand foot soldiers; some Bohemian and Moravian mercenaries; 11,000 Lithuanian, Rus’ian, and Tatar cavalry, a formidable contingent from Moldavia led by its prince, Alexander the Good, and some Samogitians).

Grand Master Ulrich had raised a huge force too, perhaps 20,000 strong. Since Jungingen had allowed the Livonian master to conclude a truce with Vytautas, however, none of those excellent knights were able to join him; in any case, the northern knights were not enthusiastic about the war, and although the Livonian master sent word to Vytautas immediately that the truce would expire at the end of the grace period, he would not send troops to Prussia or attack Lithuania’s vulnerable northern lands until that time had passed. Moreover, since Jungingen could raise only about 10,000 cavalry in Prussia the rest of his warriors were ‘pilgrims’ and mercenaries. Sigismund had sent two prominent nobles with 200 knights, and Wenceslas had allowed the grand master to hire a large number of his famed Bohemian warriors.

The numbers for both armies are very inexact, with estimates varying from half the totals given above to almost astronomical figures. In all cases, however, the proportion of troops in the armies remained about the same: three to two in favour of the Polish king and the Lithuanian grand prince. But the grand master had a compensating advantage in equipment and organisation, and especially in having nearby fortresses for supplies and refuge; and since, as far as he knew, the enemy forces had not yet joined, he believed that he could fight them one at a time. A few of Jagiełło’s and Vytautas’ commanders had served together in earlier campaigns, some against the Tatars, some against the crusaders; nevertheless, their army was composed of troops so diverse that maintaining cohesion would be difficult. Jungingen had a larger number of disciplined knights who were accustomed to fighting as units, but he also had levies of secular knights and crusaders who were prey to fits of enthusiasm and panic; he was also fighting on the defensive, better able to fall back on prepared positions and more informed about roads, tracks, and what obstacles were passable. The odds were fairly nearly equal.

An order chronicler, an anonymous contemporary continuing the earlier work by Johann von Posilge, described the preliminaries of the battle in vivid detail, thereby giving useful insights into the attitude the crusaders held toward their opponents:

[King Jagiełło] gathered the Tatars, Russians, Lithuanians, and Samogitians against Christendom . . . So the king met with the non-Christians and with Vytautas, who came through Masovia to aid him, and with the duchess . . . [T]here was so large an army that it is impossible to describe, and it crossed from Płock toward the land of Prussia. At Thorn were the important counts of Gora and Stiborzie, whom the king of Hungary had sent especially to Prussia to negotiate the issues and controversies between the order and Poland; but they could do nothing about the matter and finally departed from the king, who followed his evil and divisive will to injure Christendom. He was not satisfied with the evil men of the pagans and Poles, but he had hired many mercenaries from Bohemia, Moravia, and all kinds of knights and men-at-arms, who against all honour and goodness and honesty went with heathendom against the Christians to ravage the lands of Prussia.

One hardly expects a balanced judgement from chroniclers, but the accusations of hiring mercenaries certainly strikes the modern reader as odd, since the Teutonic Knights were doing the same thing. Men of the Middle Ages, like many today, hated passionately, often acted impulsively, and reasoned irrationally. Yet they were capable of behaving very logically too. The leaders of the armies soon gave proof that they were men of their era, acting as they did alternately with cool reason and hot temper. Reason predominated at the outset of the campaign.

The Hungarian count palatine and the voivode of Transylvania mentioned in the passage above returned south hurriedly to collect troops on the southern border of Poland. Their threat was unconvincing, however; consequently they had no effect on the campaign at all. Sigismund, as was his wont, had promised more than he was willing to deliver; he did nothing beyond allowing the grand master to hire mercenaries, though he was in northern Hungary at the time and could have raised a large force quickly.

The strategies of the two commanders contrasted greatly. The grand master divided his forces in the traditional manner between East and West Prussia, awaiting invasions at widely scattered points and relying on his scouts to determine the greatest threats, his intention being to concentrate his forces quickly wherever necessary to drive back the invaders. Jagiełło, however, planned to concentrate the Lithuanian and Polish armies into one huge body, an unusual tactic. Although adopted from time to time in the Hundred Years’ War, it was more common among the Mongols and Turks – enemies the Poles and Lithuanians had fought often. The Teutonic Knights did the same during their

Reisen

into Samogitia, but those had been much smaller armies.

In this phase of the campaign Jagiełło’s generalship was exemplary. As soon as he heard that Vytautas had crossed the Narew River he ordered his men to build a 450-metre pontoon bridge over the Vistula River. Within three days he had brought the main royal host to the east bank, then dismantled the bridge for future use. By 30 June his men had joined Vytautas. On 2 July the entire force began to move north. The king had thus far cleverly avoided the grand master’s efforts to block his way north and even kept his crossing of the Vistula a secret until the imperial peace envoys informed Jungingen. Even then the grand master failed to credit the report, so sure was he that the main attack would come on the west bank of the Vistula and be conducted by only the Polish forces.

When Jungingen obtained confirmation of the envoys’ story he hurriedly crossed the great river with his army and sought a place where he could intercept the enemy in the southern forest and lake region, before Lithuanian and Polish foragers could fan out among the rich villages of the settled areas in the river valleys. His plan was still purely defensive – to use his enemies’ numbers against them, anticipating that they would exhaust their food and fodder more swiftly than his own well-supplied forces. The foe had not yet trod Prussian ground.

The grand master had left 3,000 men under Heinrich von Plauen at Schwetz (Swiecie) on the Vistula, to protect West Prussia from a surprise invasion in case the Poles managed to elude him again and then strike downriver into the richest parts of Prussia before he could cross the river again. Plauen was a respected but minor officer, suitable for a responsible defensive post but not seen as a battlefield leader. Jungingen wanted to have his most valuable officers with him, to offer sound advice and provide examples of wisdom, courage, and chivalry. Jungingen was relatively young, and a bit hot-headed, but all his training advised him to err on the side of caution until battle was joined. Daring was a virtue in the face of the enemy, but not before.

Jagiełło, too, was a careful general. Throughout his entire career he had avoided risks. No story exists of his ever having put his life in danger or led horsemen in a wild charge against a formidable enemy. Yet neither was there the slightest hint of cowardice. Societal norms were changing. Everyone acknowledged the responsibility of the commander to remain alive; everyone accepted the fact that the commander should guide the fortunes of his army rather than seek fame in personal combat.

Consequently it was no surprise that the king’s advance toward enemy territory was slow. His caution was understandable. After all, he could not be certain that his ruse had worked; and he had great respect for Jungingen’s military skills. Without doubt, he worried that he would stumble into an ambush and give the crossbearers their greatest victory ever. He must have been half-relieved when his scouts reported that the crusaders had taken up a defensive position at a crossing of the Dzewa (Drewenz, Drweça) River. At least he knew where Jungingen was, waiting at the Masovian border. On the other hand, the news that the grand master’s position was very strong could not have been welcome.

So far each commander had moved cautiously toward the other. Jagiełło and Jungingen alike feared simple tactical errors, such as being caught by nightfall far from a suitable camping place, or having to pass through areas suitable for ambush or blockade; in addition, they had to provide protection for their transport, reserve horses, and herds of cattle. Although each commander was experienced in directing men in war, these armies were larger than either had brought into battle previously, and the larger the forces, the more danger there was of error, of misunderstanding orders, and of panic.

Judged by those criteria, both commanders deserve high marks for bringing their armies into striking distance of each other without having made serious blunders. Both armies were well-supplied, ready to fight, and confident of a good chance for victory; the officers all knew their opponents well, were familiar with the countryside and the weather, and in full command of the available technology. The resemblance of some formations to armed mobs was offset by martial traditions, individual unit drill, and widespread experience in local wars. Neither army was handicapped by dissensions in command, quarrels among units, unusual prevalence of illness, or excessive anxiety about the impending combat – these problems existed, but they were probably shared equally and were not serious enough to merit mention in contemporary accounts. In short, there were no excuses for failure.

For the Teutonic Knights, each commander, each officer, each knight was as ready for combat as could reasonably be expected. All that remained uncertain was how the battle would begin, how individuals would react, and how the affair would unfold – for those are unknowns always present in warfare. Though many individuals had participated in raids and sieges, few had personal experience in a pitched battle between large armies. Some crusaders may have gained sad experience at Nicopolis in 1396,

33

and some of their opponents may have survived Vytautas’ 1399 disaster on the Vorskla in the Ukraine against the Tatars, but those would be the only ones who knew what to expect when tens of thousands of combatants came together for a few minutes of intense struggle. Only they knew first-hand that warfare on this scale was chaos beyond imagination, with commanders unable to contact more than a few units, with movement limited by the sheer numbers of men and animals on the field, with the senses overwhelmed by noise, smoke from fires and cannon, and dust stirred up by the horses, the body’s natural dehydration worsened by excitement-induced thirst, and exhaustion from stress and exertion. This led to an irrational eagerness for any escape from the tension – either flight or immersion in combat. Aside from that small number of experienced knights there was only the practice field and small-scale warfare in Samogitia, the campaign in Gotland,

34

and the 1409 invasion of Poland. Those provided good military experience, but there had not been a set-piece combat between the Teutonic Knights and the Lithuanians for forty years, or between the Teutonic Knights and the Poles for almost eighty. Throughout all of Europe, in fact, there had been many campaigns, but few battles. For both veterans and neophytes there was consolation in storytelling, boasting, prayer, and drinking.

The Lithuanians were more experienced, but only in the more open warfare on the steppes and in the forests of Rus’. Riding small horses and wearing light Rus’ian armour, they were not well equipped for close combat with Western knights on large chargers, but they were equal to their enemy in pride and their confidence in their commander. Memory of Vytautas’ disaster on the Vorskla had been dimmed by subsequent victorious campaigns against Smolensk, Pskov, Novgorod, and Moscow. Between 1406 and 1408 Vytautas had led armies against his son-in-law, Basil of Moscow, three times, once reaching the Kremlin and at last forcing him to accept a peace treaty that restored the 1399 frontiers. Vytautas’ strength was in his cavalry’s ability to go across country that defensive forces might consider impassable; his weakness was that lightly-equipped horsemen could not survive a charge by heavy warhorses bearing well-armoured knights – he counted on his Tatar scouts to prevent such an event happening by surprise.

The mounted Polish forces were more numerous and better equipped for a pitched battle with the Germans, but they lacked confidence in their ability to stand up to the Teutonic Knights. The contemporary Polish historian Długosz complained about their unreliability, their lust for booty, and their tendency to panic. Most Polish knights – at least 75% – sacrificed armour for speed and endurance, but they were not as ‘oriental’ as the Lithuanians. In this they hardly differed from the majority of the order’s forces, light cavalry suitable to local conditions. Of the rest, many Polish knights wore plate armour and preferred the crossbow to the spear, just as did many of the Teutonic Knights’ heavy cavalry. The weakness lay in training and experience: many Polish knights were weekend warriors, landlords and young men; they were non-professionals who knew that they were up against the best trained and equipped troops in Christendom. Although some of them had served under the king previously, he seems to have drawn more troops from the north for this campaign than from the south; and it was the southern knights who had served with him in Galicia and Sandomir. Jagiełło could have called up more knights, but he could not have found room for them at the campsites, much less fed them. The masses of almost untrained peasant militia were much easier to manage; their noble lords could assume they would feed themselves and they could sleep outside no matter what the weather was. While the peasants’ usefulness in battle was small – at best they could divert the enemy for a short while, allowing the cavalry time to regroup or to retreat – they were good at pillaging the countryside, thereby helping feed the army, and the smoke of villages they set afire might confuse the enemy as to where the main strength of the royal host lay.

The size of Jagiełło’s and Vytautas’ armies must have created serious problems for the rear columns. By the time thousands of horses had ridden along the roads, the mud in low-lying places must have been positively liquid, making marching difficult and pulling carts almost impossible; moreover, the larger any body of men and the more exhausted they became the more likely they were to give in to inexplicable panic. Scouting reports were unreliable; there were too many woods, streams, and enemy patrols. Nevertheless, the king, no matter how exhausted, nervous, or unsure he and his military advisors might be, had to avoid giving any impression of indecisiveness or fear; he had to appear calm at all times. Jagiełło’s dour personality lent itself to this role. A non-drinker, he was sober at all times, and his demeanour was that of total self-control. His love of hunting had prepared him well for the hours on horseback and feeling at home in the deepest woods; he would have regarded the lightly inhabited forests of Dobrin and Płock as tame stuff indeed. Vytautas was the perfect foil; he was the energetic and inspirational leader who was everywhere at once, at home among warriors and disdainful of supposed hardships. No common soldier could complain that their commanders did not understand the warrior’s life or the dangers of the forest, or that they did not share the tribulations of life on the march.

This need to appear to be in command was itself a danger – any army on the march can be held up at a ford or a narrow place between lakes and swamps, even if no enemy is present. The commander has to give some order, any order, even if it’s only ‘sit down’, rather than seem to be unable to make a decision. Such circumstances, compounded by exhaustion, thirst, or anxiety, often resulted in hurriedly issued orders to attack or retreat that the men are unable to carry out effectively. In short, circumstances might limit the royal options to bad ones, and the perceived need for haste might cause the king to select the worst of those available. Jagiełło was certainly aware of all this, for he was an experienced campaigner. However, for many years his strength had lain in persuading his foes to retreat ahead of overwhelming numbers, or in besieging strongholds; his goal had always been to prepare the way for diplomacy. Now he was leading a gigantic army to a confrontation with a hitherto invincible foe, to fight, if the enemy commander so chose, a pitched battle in hostile territory.

Jagiełło seemed to have been checked at the Dzewa River before he could cross into Prussia. He was unwilling to attempt to force a crossing at the only nearby ford in the face of a strongly-entrenched enemy; he would not find it easy to move eastward and upstream – while the headwaters of the Dzewa presented no significant obstacle to his advance, the countryside there had once been thickly forested, and important remnants of the ancient wilderness still remained. Most importantly, although the Teutonic Knights had used the century of peace to establish many settlements in the rolling countryside, the roads connecting the villages were narrow and winding. There were too many hills and swamps for roads to proceed from point to point, and strangers could easily lose their sense of direction in the dense woods. The villagers were fleeing into fortified refuges or the forest. Although many of the inhabitants spoke Polish (immigrants not being subject to linguistic tests in those days), they were loyal to the Teutonic Order, and none wanted to fall into the hands of Vytautas’ flying squadrons – especially not the terrifying Tatars – which were trying to locate the defensive forces and find a way around them. Making peasants give information or serve as guides was part of warfare. Burning villages marked the progress of the scouting units. Though this could hardly have been seen easily by the two armies confronting one another at the ford, they might well have been aware of the rising columns of smoke.