Tete-a-Tete (30 page)

Authors: Hazel Rowley

Algren at the railroad yards in Chicago on a rainy day, 1950.

Art Shay

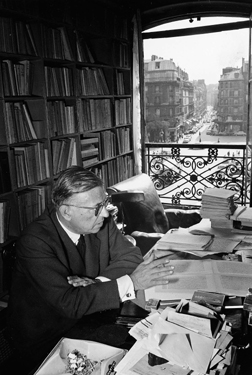

Sartre at his desk, 42 Rue Bonaparte, overlooking the Place Saint-Germain, around 1950.

Gérard Géry, Scoop, Paris Match

Beauvoir and Claude Lanzmann, Paris, winter 1952-53.

Collection Particulière/Jazz Editions

Sartre, Evelyne Rey, and Serge Reggiani at the Théatre de la Renaissance, after a performance of

The Condemned of Altona,

May 1960.

Agence Bernand

Sartre and Arlette Elkaïm outside the Coupole in Montparnasse, on March 20, 1965, two days after her legal adoption by Sartre.

France Soir

Sartre, Beauvoir, and Lena Zonina, arriving at Vilnius Airport, Lithuania, summer 1965.

Antanas Sutkus

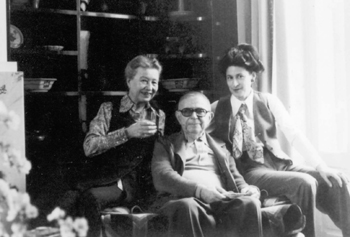

Celebrating Sartre's seventieth birthday at Sylvie Le Bon's, June 1975.

Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir

Beauvoir, Sartre, and Sylvie Le Bon, at Tomiko Asabuki's house in Versailles, 1977.

Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir

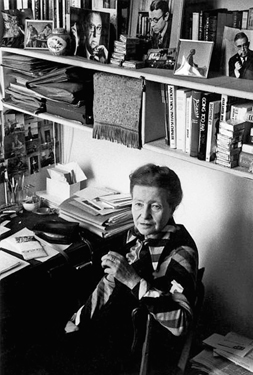

Beauvoir at her tiny worktable in the Rue Schoelcher, 1978.

Janine Niepce/Rapho

She found it unbearable to think that her love life had ended. Sartre was ensconced with Michelle. Bost (unbeknownst to Olga) was having a sizzling affair with the writer Marguerite Duras. And all Beauvoir had to dream about, as she lay in her “virgin bed,” was her “nice shining car.”

10

At forty-four, she was convinced that she had been “relegated to the land of shades.”

11

It felt like an amputation. How could she accept the idea that she would never again lie in a man's arms? She told herself she had to, for the sake of dignity. “I hate the idea of aging women with aged bodies clinging to love.”

12

In

The Second Sex,

she had already described the plight of aging women, in strong language. The tragedy, as she saw it, was that women lost their sexual desirability long before they lost their sexual desire. No sooner had they attained their full erotic development than they were observing the first signs of aging in the mirror. “Long before the eventual mutilation, woman is haunted by the horror of growing old.”

13

In January 1952, Beauvoir's typist, a woman her own age, died of breast cancer. Soon afterward, Beauvoir noticed a lump in one of her own breasts. She panicked. Her doctor said he thought it was nothing, but she should come back in six weeks. By then, in mid-March, the lump was bigger, and she was getting stabs of pain in her right breast. The doctor rolled the lump between his fingers and said she needed to have a biopsy. If it turned out to be a malignant tumor, did she agree to have her breast removed?

I repeated to Sartre, in a strangled voice, what the doctor said. His way of consoling me shows what clouds were lowering on our horizon: if the worst came to the worst, I could count on twelve or so more years of life; twelve years from then the atomic bomb would have disposed of us all.

On the evening before the operation, a nurse shaved her armpit. “In case they have to take everything off,” she said. When Beauvoir came to, after surgery, a voice was telling her that all was well. She floated off again, this time “rocked by angels.”

14

Â

The cold-war conflict had intensified. The Americans were bombing North Korea and pressuring the French government to continue its war in Indochina. Sartre was convinced that the world's main aggressors were the Americans, and that the Soviets genuinely wanted peace. Moreover, he had come to the conclusion that in France the Communist Party was the only group that truly cared about the workers. In Rome, in May 1952, he heard the news that the French government had brutally repressed a communist demonstration in Paris, and arrested the communist leader Jacques Duclos, on trumped-up charges. Sartre was beside himself with fury. He would refer to this episode as his “conversion” to communism. “When I came back hurriedly to Paris, I had to write or I would suffocate,” he said later.

15

Beauvoir had never seen Sartre sit down at his desk in such a mood of urgency. “In two weeks, he's spent five nights without sleep, and the other nights he only sleeps four or five hours,” she wrote to Poupette.

16

At the very time when most Western intellectuals were distancing themselves from Stalinism, Sartre was writing

The Communists and Peace,

a spirited defense of the Communist Party. For the next four years, he became what was known as a “fellow traveler”âsomeone who sympathized with the Communist Party without being an actual member. As he saw it, workers should join the party to defend their interests, but intellectuals needed to retain their independence.

Â

In the spring of 1952, Beauvoir found herself looking forward more than usual to Sunday afternoons, when the

Temps modernes

people crowded into Sartre's study in the Rue Bonaparte. Eager to make the journal more political, Sartre had invited some young Marxists onto the editorial boardâmen who, like him, were close to the party but not in it. His secretary, Jean Cau, had suggested his friend Claude Lanzmann. Beauvoir liked Lanzmann immediately, and enjoyed his input at the meetings. “He would say the most extreme things in a completely offhand tone,” she writes, “and the way his mind worked reminded me of Sartre. His mock-simple humor greatly enlivened these sessions.”

17

It was not his mind alone that Beauvoir found appealing.

Lanzmann was a handsome twenty-seven-year-old (the same age as Cau), with dark hair and crystal blue eyes. Beauvoir was feeling wistful. When Cau confided in her that Lanzmann thought her beautiful, she thought Cau was joking. After that, she noticed Lanzmann looking at her during meetings.

At the end of July, Bost and Olga gave a party in their apartment, on the floor below Beauvoir's, on the Rue de la Bûcherie. The group was splitting up for the summer. Bost and Jean Cau had been commissioned to co-write a travel guide on Brazil, and were about to fly to Rio. Sartre and Beauvoir were setting off for two months in Italy. Claude Lanzmann was making his first visit to Israel.

They drank a lot of whiskey that evening. Lanzmann gazed drunkenly at Beauvoir. For the first time, she made a point of talking to him. The next morning the phone rang in her apartment. “Can I take you to a movie?” Beauvoir felt a pang of excitement. “Which one?” she asked. Lanzmann's voice was soft: “Whichever one you like.”

18

Beauvoir stalled nervously. She had a lot to do before leaving Paris. Lanzmann pressed her, and she agreed to a drink the following afternoon. To her astonishment, when she put the receiver down, she burst into tears.

They talked the whole afternoon, into the evening, and arranged to meet for dinner the next day. Lanzmann was flirtatious. Beauvoir protested that she was seventeen years older than he. Lanzmann said he did not think of her as old. On the second night he stayed in her apartment on the Rue de la Bûcherie. And the next night as well. When Beauvoir set off for Milan in her little Simca Aronde, Lanzmann waved to her from the footpath. Beauvoir, who was famous in the family for her navigating skills, got lost in the suburbs trying to find the Route Nationale 7. She was glad to have a long drive ahead of her, “to remember and dream.”

Two days later, her head was still in the clouds when she picked up two English girls who were hitchhiking. It was raining and the road was slippery, and she had only just commented to them that she must be very careful when the car skidded off the road, tearing a milestone out of its socket. The milestone saved their lives. After Beauvoir dropped the girls at their destination, she stopped at a station for gas, then drove off with her bag on the roof of the car. When she realized

that the bag was not on the seat beside her, she stopped the car and ran back along the road in a panic. A cyclist came racing up, holding her bag at arm's length. “I'm losing my head,” Beauvoir thought to herself.

Sartre had taken the train to Milan, and they met at the Café della Scala, on the famous square. Sartre had never been in a car alone with her before, and Beauvoir worried that he would be impatient with her clumsiness. He was the other extreme. On the open roads he urged her on recklessly: “Pass him, go on, pass him.”

19

It was an unusually hot summer. Beauvoir wanted to visit museums, art galleries, and churches. All Sartre wanted to do was work. They compromised. In the mornings they went sightseeing, and after lunch they returned to their rooms, which were by then suffocatingly hot. While everyone else was taking a siesta, they threw themselves into their work. Sartre was working with feverish intensity on

The Communists and Peace.

Beauvoir was grappling with

The Mandarins.

Â

Sartre's closeness to the communists worried Beauvoir at first. Wouldn't it involve major concessions? She and Sartre firmly believed that intellectuals had a responsibility to tell the truth, and that this meant remaining independent. Lanzmann and the other new members of the

Temps modernes

took a different view: they were pleased when Sartre spoke out in favor of the party. Beauvoir writes: “I was put in the position of having to challenge my most spontaneous reactions, in other words, my oldest prejudices.”

20

If Beauvoir was finally persuaded by Sartre's rapprochement with the French Communist Party (the most Stalinist of all the communist parties in Western Europe), other friends were not. Merleau-Ponty, who had once been to the left of Sartre, now accused him of “ultra Bolshevism.” They had a row, and Merleau-Ponty, who had given his soul to the journal for years, resigned from

Les Temps modernes.

Beauvoir defended Sartre in an essay called “Merleau-Ponty and Pseudo-Sartrianism.”

The talk of Paris that summer was the public altercation between Sartre and Camus. In his book

The Rebel,

Camus denounced Stalinist totalitarianism and covertly attacked Sartre for sympathizing with it.

As Camus saw it, the “rebel” had an independent mind, whereas the “revolutionary” was an authoritarian character who invariably rationalized killing. Camus argued that violence is always unjustifiable, even as a means to an end.

At meetings of

Les Temps modernes

there had been heated discussions over Camus's book. Nobody liked it; which of them would review it? Finally, Francis Jeanson, one of the young Marxists who had recently joined the team, wrote a review that was a great deal more savage than Sartre would have liked. But he ran it without changes.

Camus felt betrayed. He replied with a seventeen-page open letter, addressed not to Jeanson but to “Monsieur le Directeur.” Camus was weary of being told by armchair intellectuals how he should think, he said. In his view, by embracing Stalinism, Sartre had signed up for servitude and submission.

Sartre responded with a twenty-page diatribe. “My dear Camus,” he began, “our friendship was not easy, but I will miss it”:

Your combination of dreary conceit and vulnerability always discouraged people from telling you unvarnished truths. The result is that you have become the victim of a dismal self-importance, which hides your inner problemsâ¦. Sooner or later, someone would have told you this. It might just as well be me.

21

Camus's letter had been restrained; Sartre's was brutal. For Camus, Robert Gallimard recalls, the rupture with Sartre was like the end of a love story.

22

Beauvoir rallied behind Sartre. “Personally, this break in their relations did not affect me,” she would write in her memoirs. “The Camus who had been dear to me had ceased to exist a long while before.”

23

Neither Sartre nor Beauvoir ever spoke to Camus again.

Â

Claude Lanzmann received five passionate letters from Beauvoir in Italy, before he sat down, in mid-August, to write a lengthy reply. If he had not already been in love with her, he wrote her, then her letters would have made him fall in love. He had been working ridiculously hard for

France Dimanche.

Then he had been about to write to her

when his father turned up and insisted they go fishing, to some place just outside Paris. It had been rather boring, and he had not caught anything.

He was relieved that Beauvoir was not scared by the thought of loving a madman. In the autumn, when they met again, he would explain his “madness” to her. He had booked his boat passage and was leaving for Israel at the end of August. Once there, he would try to write to her every evening. When he said he wanted to reread all her books, she had answered that she wanted to please him just as she was. He wanted her to know that he loved her just as she was. He would always love her, even if from now on she wrote only execrable books. But the fact was, he loved her books, too. In one of her letters, she had promised she would love him until her return. That was not very generous of her. He would do everything in his power to extend the season.

24

Â

Beauvoir writes that when Lanzmann returned to Paris, two weeks after she did, “our bodies met each other again with joy.”

25

Lanzmann was broke after his travels, and Beauvoir soon suggested that he move in with her. They would live together for the next seven years.

At first, the excitement of this “new boy” under her roof made Beauvoir lose her famous concentration. “I was a little dizzy the whole month,” she told Algren.

26

In the mornings they worked side by side at the Rue de la Bûcherie; in the afternoons Beauvoir worked at Sartre's. Lanzmann took longer than a month to adjust to his new situation. “For a long time I played at working,” he says.

27

He had been fascinated by Israel, and Beauvoir and Sartre encouraged him to write a book that combined reportage with personal memoir. What had it meant to him to grow up as a Jew in a country that was occupied by the Nazis? What were his feelings and observations as he traveled around a struggling new Israel? Lanzmann was excited by the idea.

The Rue de la Bûcherie apartment was small, and with Lanzmann working there as well, there were soon piles of books all over the floor. The only way they could manage was to eat all their meals out, often at La Bûcherie, the café in the square.

Â

Lanzmann insisted on using

tu

with Beauvoir. He could not possibly be her lover and address her with the formal

vous,

he said. Years later, Beauvoir told an interviewer:

I've always found it very difficult to address people in the familiar. I don't know why. I did so with my parents and that should have enabled me to do so with other people too. My best friend Zaza always addressed her girlfriends in the familiar, but she used the polite form with me because I did so with herâ¦. I address nearly everybody in the polite form, apart from one or two people who have forced the familiar on me.

28