Tending to Grace (7 page)

52

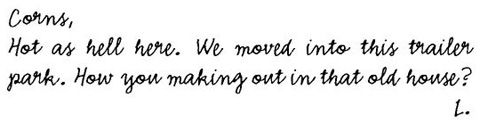

Another postcard waits for me on the table. This one has a picture of a desert sun beating down on a house trailer:

53

“I guess I be needin' some glasses right away,” Agatha says, looking up at me from her place at the table. “Who's this one from?”

I open the envelope for her. “S-s-s-senior Citizen Center. They want you to b-b-buy a cookbook.”

“Don't they know I hate cookin'?”

I smile and let her fix me a cup of sassafras. I'm starting to like the way it fills me.

54

I'm measuring whole wheat flour into the bread bowl, trying not to put in seven scoops of flour rather than six, when the screen door slams with a bang.

“Corney.” Bo hurries into the kitchen, her pants soaked, mud up her arms and across her cheeks. “I need another frog. The race is tomorrow.”

“Wh-wh-what happened to the other one?”

“My brother let it go. I been down the creek for an hour, but I can't catch anything. I need you to help me get one.” She drops her canvas sack on the floor.

I look up at the clock. If I want this heavy whole wheat flour to rise, I have to knead it for a full ten minutes. I plunge my arms deep into the dough, pushing it down into a pancake, folding it back on itself, and punching it down.

“I n-n-n-never caught a fr-fr-frog before, Bo.”

“But with two of us, maybe we could trap one. You promised you'd go to the race with me.”

I put the dough into a bowl, spread a towel across the top, and set it on the counter in the sun.

“I know,” I say, wiping my hands on a towel.“But I didn't promise I'd c-c-c-catch a frog.”

55

Over and over, I run through the water toward Bo and watch a frog jump almost close enough for her to catch in her outstretched arms.

The water is cold. My waterlogged overalls weigh me down, my body a heavy barrel I pull through the water. A frog jumps close to Bo and this time she dives for it. When she stands, black mud from the bottom of the pond covers her face and plasters her hair.

“B-b-b-bo, this isn't working at all.” Mosquitoes bite my neck. Each time I swat at them, I leave a muddy handprint behind.

“Maybe not. Let's go around the other side. Come on.”

We scramble along the edge of the pond and across the brook where the water enters. Blueberries hang so low at the edge they bob like marbles on the water.

I see a frog close to me this time and I spring, grabbing the air and landing facedown in the mud. When I stand up, Bo laughs.

“Is that the way you do it in the city?” she asks. “Leapfrog? You're not supposed to eat the mud.” She laughs so hard I'm sure she's going to pee her pants. I try to wipe my face with my wet sleeve.

A car slows and stops. Bo splashes around the blueberry bushes and doesn't hear. A man walks up to the crest of the hill and looks down at us. I can tell the moment he sees her.

“Bo!”

She looks up at him, her hair hanging in wet strings. “Pa!”

“I never said you could come here,” he says, rushing down the bank and wading toward us. “You expect us to do all your work?”

I don't know why he hasn't seen me. I am standing in a shadow; maybe I am a shadow. But when I take a step forward, he jumps. “Who the hell are you?”

I recognize him as soon as he speaks. He's the man from the bank.

“We were just catching frogs, Pa. That's all. I finished all my chores before I came.”

He hasn't taken his eyes off me. “Who's this?”

I take a deep breath. “C-c-c-c ...” Then I stop, unable to go on. I might be standing knee-deep in water, but my face sparks. He reaches for Bo's arm, misses, and wades closer. He looks at me without blinking.

“Who are you?”

“Cor-cor-cor . . .” I stop and start again. “C-c-c-cornelia.”

He recognizes me; I can see it in his eyes. Then he looks away.

“Dimwit,” he says, half under his breath. He drags Bo out of the water, up the hill, and into the car. I sink to a rock and reach up to wipe the mud from my face.

56

I carry a frog into Agatha's kitchen a couple of hours later. It squirms so much I keep tightening my fingers around its slender body. It is half the size of the one Bo caught a few days ago. But it is alive and green. I can attest to the fact that it hops as high as my face.

Agatha looks up from the cucumbers she is slicing.

“What happened to you?”

I tell her the story and drip on the floor.

“Maybe you should race it for her,” Agatha says.

57

“Name, please.”

A boy wearing a sign on his chest that says FROG JUMPING COMMISSIONER looks up at me. Behind him, someone has taped a set of rules, written on poster board in thick black paint:

OFFICIAL RULES

No toads.

Any frog jockey who is rough will be asked to

leave the race.

A jump is measured by running a string from

the start line to the frog's front feet after it

has hopped three times.

DO NOT ARGUE WITH THE FROG COMMISSIONER.

ALL JUDGMENTS ARE FINAL â¢

58

The frog commissioner looks up at me when I don't answer.

“I said, Name, please.”

“Ummmmm.” I try to ride the vibrating wave of the

m

sound, hoping I can break into

Cornelia

without blocking on empty air. I look for Bo in the crowd, even though I don't expect to see her. A boy with a frog twice the size of mine edges forward. “What's going on?”

“If you want to race, I need your name,” the commissioner says again. “Are you going to race or not?”

I take a deep breath and push my foot into the ground. “C-c-c-c ...” I stop.

“What?”

More of the kids behind me move closer now. “C-c-c-c-c ...” I want to sink into the ground.

The commissioner looks at me unbelieving, then laughs. “What's the matter, forget your own name?”

I take another breath and laugh right along with him. Then I spell my name. The easy way out is as simple as J-e-l-l-O.

59

“Jockey, on your mark.” A couple dozen kids kneel down around the circumference of the starting circle while I hold my frog in front of me. They're all supposed to keep their frogs under control while I jump mine. This is a one-frog-at-a-time race.

The boy on my left holds a frog with massive legs the size of my entire frog. My frog's legs look like knitting needles.

One kid loses control of his frog and watches it jump crazily out of the circle and across the pavement and the boy screams out, “Stop, stop!” but of course it doesn't listen. I tighten my grip.

“Get ready!” screams the frog commissioner. “Go!”

60

Two chained German shepherds growl and bark as I round the corner and walk up Bo's driveway. A woman walks out of the house and wipes her hands on a dish towel and watches me from the porch. Two toddlers grab at her legs, peeking from behind her floured apron. Her stomach sticks out so far with a baby on the way it looks as if she's tucked a laundry basket under her dress.

I glance around quickly for the father. There's no car in the driveway. Several chickens peck at the ground, which is worn thin and bare and hard as an old carpet. A cracked bathtub tilts on the grass, filled with muck.

“Is B-b-b-bo here?”

The mother looks me over. “You Lenore's girl?” Her voice softens. She makes my mother's name sound welcoming, promising, kind.

I nod.

“Bo told me you're at Agatha's. You look just like your mother. Like Agatha, too. Come on in. I've got something for you.

“Bo's out in the back with the boys. I baked this morning.” We walk into the kitchen and she pulls a chocolate cake out from beneath a checked towel that sits on the stove and wraps it in tinfoil and hands it to me.

“There's no frosting on it so it won't get all over everything. Would you like a piece? I've got another. Have a seat.” She points to a table in the middle of the kitchen that sits on an orange and brown braided rug.

The toddlers peek at me from behind her skirt and she drags them along behind her as she pulls a jelly glass from a cupboard and fills it with milk.

Faded curtains cover the window over the sink. An old white sink sits near the stove with a built-in drainboard on the end. The room smells like chocolate.

“All those potatoes. Agatha really helped us over the winter. My husband found a job, so things are better now. You can tell Agatha. And tell her I appreciate the vegetables Bo brings home, I surely do.” She smiles and cuts me a slice from the other cake and lays it in front of me.

“How's your mother?”

I shrug.

“She still the same?”

I nod, although I'm not sure if we're talking about the same thing.

“She'll come around. Sometimes it takes a while.” She smiles at me again.

I'm not so sure I should have to wait at all. I'm pretty sick of waiting, actually. But instead of saying anything, I take another piece of cake. Bo is lucky to have a mother like this, I think. They both have the same kindness. I feel the warmth coming up through me as I take another bite of cake.

61

Bo covers her eyes and counts and three little boys dash away from her as I walk around back. A rusted swing set with one swing missing stands near the house.

“I got you a r-r-ribbon,” I say, walking up to her. “A yellow one.”

“How'd you do that?” She pushes the bangs out of her eyes and turns to the boys. “Don't go too far!”

“I caught a frog in the pond. I won a yellow ribbon.”

“Wow, that's so great, Corney. Let me see.”

I pull the ribbon out of my overalls pocket and give it to her.

“Wow, I wish I could've seen it. How'd you catch the frog?”

“Took me the rest of the morning.” I laugh. “You don't get m-m-m-money for third place, though.”

She strokes the ribbon. “That's okay. Was it fun?”

I smile. “Yeah. I n-n-n-never raced a frog before.”

We both laugh.

“Want to play with us?”

I shake my head. “I have to go. But if you w-w-want to come over, I can show you some stuff. About r-r-r-r-reading, I mean.”

“You mean it? You really do?” When I nod, she jumps up and hugs me and it feels pretty good as I hug her back.

62

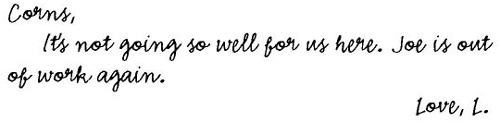

The next day I receive a postcard that sends a storm rushing across the desert.

Good, I think. She'll be back for my birthday. A mother doesn't forget her daughter's birthday.

63

I bring Bo to the library. I scan the shelves, looking for the right book. Finally, I put

Teach Your Child to Read

on the counter. Warm Milk looks up at me and smiles. I look at Bo. “I'd like a library card,” she says.

Warm Milk types the card for Bo and hands it to her. “Would you like one, too?”

I shake my head and plant myself facedown again.

64

“I'll shut the door if you think your p-p-p-pa will come.”

Bo slumps at the kitchen table. The heat hangs heavy inside the house and out. The black-eyed Susans droop after an afternoon at the back step. We watch them through the screen door, newly fixed by me, that barricades us against the flies and mosquitoes that followed another bout of humidity.

“Oh, don't worry about him none.” Bo laughs and slurps the lemonade I put in front of her. “He's workin' till midnight. He hates it, but our nights are nice and quiet now.”

I pull out the phonics book and sit down beside her. “All right, then. If you're sure.” I open the book. “We're going to do short v-v-vowel sounds first.” I point to a letter a. “This makes a sound like the

a

in

apple

or the

a

in

ant

.”

Then I show her an

e

. “This m-m-makes a sound like the

e

in

echo

or

egg

.”

I point to the

a

again.

“Aa, aa, aa,”

I say. “Now you try.”

“Aa, aa, aa.”

Bo looks at the page intently. Her bangs flop in front of her eyes and she pushes them away. “How come it doesn't sound like the

a

in

plate

?”

“That's for l-l-l-later.” I glance out the door. “Now come on. You have to learn this.”

“I just don't get itâwhy doesn't it sound right?”

There's a bang at the door; we both jump before we realize it's Agatha.

“I got all these tomatoes here,” Agatha yells in to us. She dumps the tomatoes into the sink and covers them with water.

“Okay,” I say, turning back to Bo,“it just doesn't make s-s-s-sense to ask all these questions. Everyone asks these questions and it gets them nowhere. Now just say after meâaa, aa, aa.”

Bo rolls her eyes.

“Aa, aa, aa

.

”

She turns her face into a sour ball. “I don't want to do

aa, aa, aa,

Corney, I want to read. This is for babies.”

“Bo,” I say, raising my voice just the tiniest bit, “you have to start at the beginning if you don't want to

be

a baby.”

Bo squinches her face and tries again.

“Aa, aa, aa,”

she says softly.

“That's b-b-better. Now for

i,

you make the s-s-sound like in

itch

or

igloo

. Say itâ

ih, ih, ih.

”

Bo crosses her eyes at Agatha, who laughs.

“This is so dumb,” Bo complains.

“Ih, ih, ih.”

I ignore them.

“Now why don't we p-p-play a game,” I say. I tear a piece of paper into four squares and on one square I write the letter

a,

on another an

e,

and on a third an

i

. Then on the fourth square I draw a goose.

“I told you this is for babies,” Bo says.

“No, it's going to be fun. Now look. We'll f-f-f-flip these cards over and if you get one of the vowels, you make the sound, but if you get the goose, I make a honking sound and flap my arms like this.”

Agatha pulls a tomato out of the sink and begins chopping.

“Okay, pick a card.”

Bo picks the goose.

“Honk, honk, honk, honk,”

I scream. I stand up and run around the table, flapping my arms.

“Honk, honk.”

“Why ain't you teachin' her the words, silly goose?” Agatha says from the counter, chuckling to herself.

“It m-m-makes sense to go slow and make it fun so she can learn it this time,” I say, slightly miffed. “I b-b-bet if they made it fun in school, Bo would have learned it the f-f-f-first time around.”

Agatha pulls out a knife and starts quartering the tomatoes. “At least she's not too scared to go to school.”

I ignore Agatha and turn the page. “We say

o

like

ostrich

.”

Bo interrupts me. “Yeah, Corney, I never knew anyone who reads as good as you. You could go to college.”

College? Me? Do you have to talk in college?

Agatha interrupts my thoughts. “How long you goin' to hide, Cornelia?”