Tending to Grace (4 page)

27

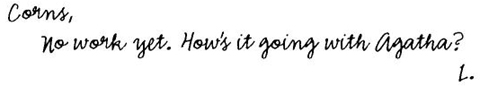

The next day Agatha slaps a postcard on the table with a picture of a seagull in flight.

I flip it over, afraid to breathe.

I notice right off there's no

Dear Cornelia,

no

Love, Mother,

and no return address. I wonder if my mother saw her reflection in the glossy front of the card. I throw it in the trash. Then I pull it out and put it in my pocket and walk out to the garden. My carrot seedlings that I replanted lie withered on the ground. I try to stand them up again by mounding their feet in little hills of dirt.

“Don't you know you can't be replantin' carrots?” Agatha says as she walks up from behind. “Their roots ain't strong enough to go down deep.”

28

My fingers scratch themselves raw on a Brillo pad as I bear down harder on the kitchen table. Agatha forgot to wash her molasses spoon, to the delight of the flies. She is so irritating I could spit on her. I push harder and turn the table into a field of steel-blue suds.

Bertha chugs up the driveway and as Agatha slams the door of the truck, she screeches, “Cornelia! Look!”

She rushes into the kitchen and grabs my wet arm, pulling me out the door and into the yard. White fluff swirls all around me.

“I bet you never saw anything like this!” she says. “I'll give you three guesses what it is, and it's

not

snow!” She holds up her fingers and catches the cotton wisps that drift past. I walk out into the middle of the lawn and look straight into the white softness. The fluff looks like large airy snowflakes. I reach for one and hold it in the palm of my hand. “M-m-milkweed?” We raised monarch butterflies in science once.

“No,” she says, laughing and spinning around and around. Her braid unropes itself from its pins and flies behind her. “They're dandelions. They're sending off their seed, becomin' something new. This is a lucky day, Cornelia.”

She leaps into the air, reaching high for the fluff sailing past, catches some, and tosses it out again. The flour white softens everything and begins to smudge the wrinkles on her face. She springs higher and higher as the wind picks up and sends the wisps heavenward. Even I can't help but smile.

I walk deeper into the gentle flurry. Very slowly, I begin to twirl around, first one way and then the other. I raise my arms, reaching up and pulling pieces of fluff into my hands. I breathe deeply and twirl faster, faster, and as I'm twirling, I'm laughing.

For just a moment, I want to rush into the house and fling on my black Salvation Army dress and dance back through the white softness. And I wouldn't give a hoot about the meanness of anything.

29

“You can eat them, you know,” my aunt says that night as she peels a potato at the kitchen table. “Dandelions, I mean.”

“The fluff?”

“No,” she says, laughing so hard she has to put the potato down. “You really aren't from around here, are you? You eat the leaves. Sauté them up with garlic, toss them in a salad. Either way, they're out of this world.”

“Y-y-you'd eat anything, wouldn't you?”

She picks up her potato again and starts peeling.

“You get hungry enough, you eat just about anything. Except for coffee. Rot your stomach out, that will.”

30

The temperature soars and my aunt and I begin fighting over the chores, the food, the mess, my reading, the lack of coffee in the house. We slam doors and storm outside. She snaps at my cleaning; I yell at her mess. We fume at each other like two chickens in the same sweltering roost.

I wipe the sweat off my forehead and sweep the cobwebs off the beams overhead. I wash down the walls, and while I'm at it, I try to make sense of my life. There is no music in this house, other than the birds outside; no radio, no television. I have nothing to distract me. What now, what now, what now? I ask over and over as I wash the refrigerator, sweep the floor, scrub the stairs, wash the windows.

I slam the cupboard door and run outside when I find little brown pellets at the back of the cupboard.

Agatha kneels beside her squash plants, checking for bugs.

“There's m-m-m-mouse poop in there,” I say when I reach her.

She looks up at me. “Set some traps.”

“I c-c-can't believe you live in such a m-m-m-mess,” I yell, kicking the pumpkin plant in the row next to her, tearing half of it out of the ground. I run up to the fields above the house, sinking into the grass that now reaches to my thighs, screaming until my head aches. All I want is a life that is tidy, where the edges are hemmed and straight and the corners are tucked and tight as new cotton sheets.

31

Agatha whacks her moccasins against the side of the fireplace when I walk back into the house. Caked mud flies off the old leather and onto the floor. She ignores the dirt and walks into her room and tosses the moccasins on her bed.

She hasn't touched the mouse droppings, so I take everything out of the cupboards, including old tins of spices with chipped paint hanging off their faces. I sweep out the cupboards, and then I sprinkle an entire can of tub cleaner inside and scrub the wood until it bleaches to a soft buff.

I find mousetraps in the only closet in the houseâa little sliver of a thing beside the back doorâand I load them with peanut butter and set them behind the plates.

“What you doin' with that there rat trap?” Agatha asks, walking out of her room. “You'll have guts all over the place if you use that. It'll take a mouse head off faster than an ax whacks a chicken. That's for the rats that get into the grain in the barn. What you doin' in that closet, anyway?”

“I was cleaning it s-s-s-so I could p-p-p-put the big soup pot in there. I f-found these.”

“Well, top of the stove works just as well for the soup pot. I don't put nothing in that closet 'cept for traps and tools. That crack that's in the back of it goes clear to the outdoors. You can see the stars at night from in there if you look up. It's kind of fun. You should try it sometime.”

She pulls a sugar cube from her pocket and munches it slowly. She no longer offers them to me.

“You gotta get used to livin' in a house like this, Cornelia. Why don't you stop wastin' your time and come help me in the garden?”

“If I'm going to l-l-l-live here, I've got to clean it up. How can you live like this?”

She chuckles.“Don't look at it. That works pretty good,” she says, walking back outside.

I kick a chair when she leaves. Then I make my way down to the basement. Dozens of jars of home-canned food cover one sloping shelf, but I can't tell what's inside until I wipe the dust with my shirt. Old stringy pickles float in some of the jars, carrots or something orange fills others, and some are stuffed with something that could be beets. Green goo fills a couple dozen jars on the shelf above. I toss them all into old bushel baskets and carry them out to the barn.

32

Bertha is loaded with a fifty-pound bag of oatmeal, a twenty-five-pound bag of whole wheat flour, and another of brown rice. We tuck tofu between us on the front seat, lentils on the floor, and dry milk powder in the crawl space behind our seats. Agatha fit right in at the health-food store; I was the only one not wearing moccasins.

“Don't you eat any meat at all?”

“Not for a long while,” she says, loading a bag of carob chips. “Doesn't make much sense to me, stuffing myself with dead animals.”

The store is in Dover, two towns away, and as we drive back to Agatha's, we pass a bank, a bookstore, a whole string of little shops selling ice cream and antiques and doughnuts.

“C-c-c-can you get me a c-c-coffee?”

“Nah,” Agatha says, pulling a thermos from under the seat. “I brought the sassafras.”

33

We drive in the slow lane, like we do everything else. As we head off the highway and into Harrisville, Agatha pulls Bertha over to the side of the road. Two wicker chairs sit near a mailbox with a FREE sign hooked to their backs.

“Well, I can see those out by the barn, can't you?”

No, I can't, I think as she stops. They are the same tomato green as the truck and are covered with mud. “They don't even stand up right.”

Agatha doesn't listen. She climbs onto the back of the truck and pushes the oatmeal out of the way. “Are you going to help me or not?”

As we get the second chair onto the truck, a pickup rumbles to a stop. “Agatha!” A man jumps out and hurries toward us. My aunt plants her feet into the gravel.

“You ladies need a hand?”

“You stop just to give me help, Moss?” Agatha says.

The man laughs. “Sure.”

“Well, the job's already done. Two chairs for my garden.”

“I did want to talk to you about that woodlot, Agatha. You gonna sell it to me this year?”

She snorts. “I knew there was more. I got the same answer I gave you last year, Moss. No.”

“You can make a good pocket of cash off itâI keep telling you that, Agatha.”

“And I keep telling you, I'm not lettin' no one buy my land.”

He takes off his cap and wipes his forehead with his arm. “Your house, Agatha, it could surely use a little money put into it. Be a shame to let an old place like that go.”

“My business, not yours,” she says.

He winks at me. “I'm Moss, Moss Jackson.” He reaches his hand out to shake mine. “I own the land right up to Agatha's. Isn't that right, Agatha?” He looks back at me. “And you're?”

Think about

anything

else, I tell myself as I reach out my hand. I turn to Agatha, hoping she'll tell him who I am. Instead, she looks back at me. I begin turning myself to stone.

Think about all the fish heads and old bologna sandwiches and half-eaten Pop-Tarts that rot inside all the garbage bags at the dump, I tell myself. Think about tuna in a lunch box, six days old.

“Ummm,” I say finally. I breathe deeply through my nose. I loop my thumbs in my belt loops and pull until they are as red as cherries. “C-c-c-c ...”

A grin moves across his face. He chuckles. “Cat got your tongue?” I turn miserably to Agatha. She is not chuckling. She is looking straight at me.

Why doesn't she do anything? She could just say my name, make this all go away, but she stands there, still as pond water.

I am a stone, sinking. “C-c-c-c-c ...”

He looks down, away. He turns to Agatha. “You change your mind on that woodlot, you give me a call now, you hear?” He hurries to his truck and climbs in, starts it, and drives off.

Agatha looks at me a long time. She puts her arm on my shoulders and then we walk to the truck and ride home in silence. I want to slip into the quiet and never talk again.

34

“You c-c-c-could have helped me,” I say later, after we push the chairs off the truck and shove them against the barn, where they sit in the shade of the maple tree. Agatha flips a cucumber basket upside down and sprawls in one of the chairs and puts her feet up. She raises an eyebrow. “How?”

“You c-could have said my name. S-s-something.”

“Seems like no one should be doin' that but you.”

I turn away and storm into the house.

35

Agatha sleeps under a heap of sheets and blankets, with her feet sticking out the bottom of her bed. The whole thing drives me crazy and one day I tackle her room. I strip the bed and wash the sheets and blankets and hang them on the line. I wash her overalls and T-shirts that are strewn over chairs and across the bedposts and are stuffed behind the door. The dust chokes me as I yank things out from under her bed. It's an archaeological dig: I pull out a stuffed owl with one eye missing, yellowed newspapers from 1961, a purple hat with a long sweeping feather, and a small wooden box with a hinged cover.

I brush off her bed with my hand and sit down and open the cover of the box and find the tiniest sweater I've ever seen, a pair of booties, mittens the size of strawberries, and a hat that could fit an orange. A thin thread of lace edges the sweater and when I rub it against my cheek, the yarn feels as soft as the dandelion fluff in the yard.

“What are you doing?” Agatha's voice claws at me; her eyes are nickels on fire. In one leap she hovers over me, pulling the sweater out of my hand. “I ain't never told you to clean in here. Now get out.”

I run out to a tree in the backyard where the branches start low enough to climb. From up high, I can look across the backyard to the fields. A bird struggles to put branches into a tiny hole in the bird-house by the garden. The branches stretch longer than the bird, but she keeps trying to push the sticks through the hole, first one way, then the other, trying to make a home in a place that doesn't fit.

36

Not one car passes by Agatha's house in half a morning. My mother must have known what she was doing, leaving me at a house three miles from the center of town, a place with no train tracks, no buses, no taxis, and no easy way out. I look up at the mountain in the distance.

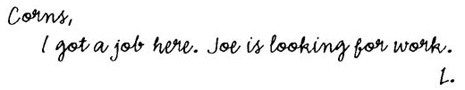

A picture of fried eggs and sausages covers the front of my mother's next postcard. A bright neon light spells out the words

Lou's

Diner

.

Her handwriting is quick and sloping. I can tell she has other things to do.