Sudden Sea (18 page)

The Hurricane of 1938 had reached the capital of Rhode Island. Trees were falling and pedestrians were having trouble keeping their footing. In a matter of minutes, water was washing over the running boards of the cars in front of the Outlet and filling the store’s cellar. Refrigerators and stoves floated up from the basement.

A few blocks away in the newsroom of the

Providence Journal,

the editors were laying out a sports extra when a warning clattered over the Teletype machine:

Serious storm headed for southern New England. Tropical disturbance will cross LI Sound and reach the Conn-RI border early tonight.

The time was about 3:40

P.M.

The

Journal

editors were debating whether to insert a weather story in the sports extra when the presses stopped, ending the discussion. The city turned black, as if a municipal plug had been pulled. In the murky light, everything not cemented down was flying or floating. Hundreds of plate-glass store windows popped and their contents spilled into the street. Streetlights shattered, raining splinters of glass that jabbed like daggers on the wind, bloodying many trying to flee the storm.

A rave review in the morning

New York Herald Tribune

had described

Old Haven

(Houghton Mifflin, $2.50, a new novel by David Cornel de Jong, as “a well-wrought story set in a landscape borrowed from Breughel.” The author wasn’t reading his glowing notice, though. He was marooned in the Providence Arcade. The first indoor shopping mall, the Arcade runs the width of a city block and opens on two busy downtown streets, Weybosset and Westminster. It was designed in 1825 in the style of a Greek Revival temple with six massive granite pillars at either entrance. Three floors of shops connected by long, open iron balconies overlook the ground-floor atrium, and above the atrium is a long glass skylight.

When the hurricane roared in, the Arcade became a wind tunnel. Shoppers clutching their bags, salesgirls tottering on spike heels, and bootblacks, their polishing boxes slung over their shoulders, tried to dash across Weybosset Street. The wind stopped them. It was “an invisible wall in front of us, holding us impotently suspended,” de Jong remembered. A store window crashed inches away. A shard of glass slashed the throat of a woman just ahead of him. Her blood splattered his face. When he reached her, the wind pushed them into a revolving door with the crowd of shoppers, two and three in a single compartment, and spun them repeatedly. De Jong took refuge in the third-floor office of a lawyer friend. From there he watched as the hurricane drove up Narragansett Bay.

The wind came first, brining sporadic showers, spraying spin-drift miles inland, filling the air with brine. If you licked your lips in Providence, thirty miles from the nearest beach, you tasted salt. The ocean was a step behind. The narrow head of the bay compressed the storm surge into an ever higher dome of water. Spilling into the downtown district, the rushing water tore down wharves and hurled a couple of coal barges across Water Street. It swept into the heart of the city, swishing through the streets, bolting around corners, gurgling into stores and offices, and surrounding City Hall.

Solomon Brandt, a printer, was working in his shop on the second floor of a city office building. “The first time I looked out, I recall distinctly there was no unusual amount of water,” he recounted. “As I returned again from the presses no more than five minutes from the previous time, I saw the most unusual sight I had ever seen in all my life. The water was rushing through the streets. It rose almost as fast as if you held a glass in front of a spigot.”

The bay washed over Providence — six feet, ten, twelve — over the roofs of cars, over the tops of trolleys — fifteen, seventeen feet — inundating three miles of industrial waterfront and the mile-square business district. In thirty minutes the service station where Lally Dwyer stopped for gas in the morning on the way to her job at the telephone company, the newsstand where she bought the morning

Journal,

the soda fountain counter where she ate lunch, were submerged.

Workers trying to leave their offices at five o’clock plunged into a whitecapped lake, 17.6 feet at its deepest point. Pedestrians wrapped themselves around lampposts and clung to fire escapes. Drivers who managed to get free of their cars swam into stores. Trapped passengers dove through the windows of trolley cars. In the gray, engulfing water, cars and trolleys disappeared, their batteries shorted, and a muffled din echoed from the submerged vehicles. Car horns blared and trolley bells clanged like the bells of hell, and their lights glowed eerily through the water.

Almost fifteen hundred moviegoers, marooned in the city’s five downtown theaters, crowded into the highest balcony seats as the water rushed in. At the RKO Albee, the manager swam over the orchestra seats to reach the balcony stairs. Pierce’s shoe store on the corner of Dorrance Street, where the walls were stacked floor to ceiling with shoe boxes, filled with water so fast that the clerk and a customer were sent scooting up to the top of the sliding ladder. They hung there watching black-and-white saddle shoes, cordovan wing tips, and patent leather high-heeled pumps with open toes and ankle straps step out on their own. Down the street, the H. L. Wood Boat Co. launched rowboats through the windows to rescue the stranded.

From the third-floor office de Jong watched the city flood and later wrote a vivid account for

Yankee

magazine:

A gray light seemed pressed between the high buildings and weighed on murky, churning water in the street. People floundered in all directions, at once abetted or opposed every inch of the way by the awful winds. Directly below us, an old man, neck deep in water, lifted his hands and sank. We craned our necks but never saw him again. He was drowned. “Must have been drunk, the crazy fool,” three men said simultaneously. But their eyes said he could not have been drowned, not there, our eyes are crazy. The men turned away from the window, all three, and lighted cigarettes.

As de Jong continued watching the bizarre floating parade below, a blond mannequin from a dress shop swam into the street: “Holding her head high, her visage vacant, never sinking, she pirouetted on the flood like a well-mannered debutante.” Next came a desk with a pencil sharpener clamped on one corner, its arm revolving in the wind; red balls went flying by “like puffed exotic fish”; then a chain of people chindeep in water. The last link was a woman. Her grasp slipped, and the rushing tide pulled the others away. They struggled back and linked arms with her again. She slipped loose a second and a third time, too frightened and hysterical to hold fast, and each time the others battled the current and went back for her.

De Jong was riveted on the human drama until someone in the office shouted, “Look at the blonde!” The mannequin “had tilted her head through a store window. She seemed to be peering haughtily inside” when a heavy beam borne on the rushing water smashed into her, and crushed her. A woman in the office screamed. Then the tension broke, and everyone laughed.

Seven people perished in the streets of downtown Providence, three men and four women, drowned or crushed in their cars. Roaring white water swept one man to his death right in front of the steps of City Hall, as incredulous workers watched from the windows. A couple of blocks away, Leo Carter, the janitor at the

Providence Tribune

building, lowered ropes from the fire escape and, one by one, pulled five people out of the water to safety.

At Union Station, where passengers waited for trains that never came, the wind took off the metal roof and rolled it up like a rug. The station was beyond the reach of the floodwater, and many found refuge there. One man, Joseph Vogel, was dressed to the nines in morning coat and top hat. Vogel was on his way to his wedding at the Narragansett Hotel in the heart of downtown Providence. He nipped into the station to get out of the storm and became marooned there. While his bride and her family waited at the Narragansett, strangers seeking refuge from the storm poured into the reception room, ate all the food, and drank all the champagne. The Vogels were finally married in the evening by candlelight. They waded a few blocks across town to the Biltmore Hotel. Although the first floor was submerged, they were offered a candle along with the wedding suite.

In Rhode Island’s major banks, floodwater inundated the vaults and seeped through the seams of safe-deposit boxes. The next morning, bank managers strung clotheslines the length of the vaults, and moneyed Rhode Islanders trekked down College Hill, poured the foul water out of their boxes, and hung their stock certificates on the line to dry. One loss was irretrievable. The original charter of Brown University, written in 1765 by hand on parchment paper, had been stored in a downtown bank for safekeeping. The salt in the floodwater stiffened the parchment and erased the ink.

All through Narragansett Bay, the hurricane emptied marinas and demolished country clubs, yacht clubs, casinos, and beach pavilions. At Rocky Point, an amusement park on the bay where Rutherford B. Hayes made the first telephone call ever dialed by an American president, the famous roller coaster collapsed. The cavernous restaurant (with seating for a thousand was reduced to the boilers, and the water rose so high that bathing suits dangled from the beechwood trees still standing after the storm.

At Narragansett Pier, across the bay from Jamestown, thirty-foot waves crushed breakwater boulders and gouged out Ocean Road, which meanders south to Point Judith. They pushed Sherry’s Pavilion, operated by the fashionable New York restaurateur Louis Sherry, across the road, beat down Palmer’s Bathhouse just to the south, and left the pricey Dunes Club, a mile or so north, in ruins. All that was left of the Narragansett Pier Casino was the massive Norman tower designed by Stanford White.

In Newport, where the Vanderbilts and Astors entertained in high style and summer getaways were modeled after Versailles, trees cracked, a wing tore away, a roof caved in. Otherwise, the grand mansions were unharmed. Most of them occupied high ground, where only the wind could reach them. In the lower-lying areas of Newport, the damage was much worse. The

Promised Land,

a 135-foot fishing boat, spun across the harbor and was tossed up on the city wharf. Out on Ocean Drive, wash-outs were a hazard, and Bailey’s Beach and the Clambake Club, favorite hangouts of the wealthy and privileged, were demolished. At the more egalitarian Easton Beach, the storm reduced the carnivalstyle carousel and roller coaster to kindling wood. Many were happy to see them go.

Hartley Ward of Newport kept a record of the hurricane day. “The whole summer season had been one of most unusual weather,” he wrote, “nothing like it had been noted in Newport in many years.” At two o’clock Wednesday afternoon, the sun was still shining on Narragansett Bay, but the surf was brushing over the seawalls and the tide was running high. By 3:30

P.M.

, the skies were threatening; by four o’clock, the gale had reached Newport. As Hartley Ward reported:

There was no holding things down and it was all one’s life was worth to walk in the streets. The tide was way up in Thames Street. The wind was coming in terrible gusts, pulling trees up by the roots, and knocking people down. Ambulances were rushing, sirens screeching through the din, signs clanging along the sidewalks, the horns of five hundred submerged automobiles blowing and the rain pelting down in torrents. The steeple of the First Baptist Church tottered and tumbled into the street, its bell clanging a terrible dirge as it landed.

Other parts of the island took a thrashing, too. One of the worst hit was Island Park, Portsmouth, a finger of beachland at the northeastern end. The next day some Island Park residents found their homes in a peach orchard a mile away, and they were the lucky ones. Nineteen died in Island Park.

The colonial village of Bristol, home of the first Fourth of July parade, was pummeled and cut off from the rest of the state for two days. The hurricane smashed the Bristol Lobster Pot, one of the most popular seafood restaurants in Rhode Island, and wrecked the Herreshoff boatyards, where Captain Nathaniel Herreshoff, known as “the Wizard of Bristol,” had designed and built eight consecutive America’s Cup defenders. After 1938 new technologies and demands for sleeker, swifter styles would relegate the classic sloops to history.

The Tempest

I

n towns and villages across Rhode Island, schools were letting out as the hurricane stormed in. Children, dismissed into the fury, were greeted by wind and rain, crashing trees, and crackling live wires.

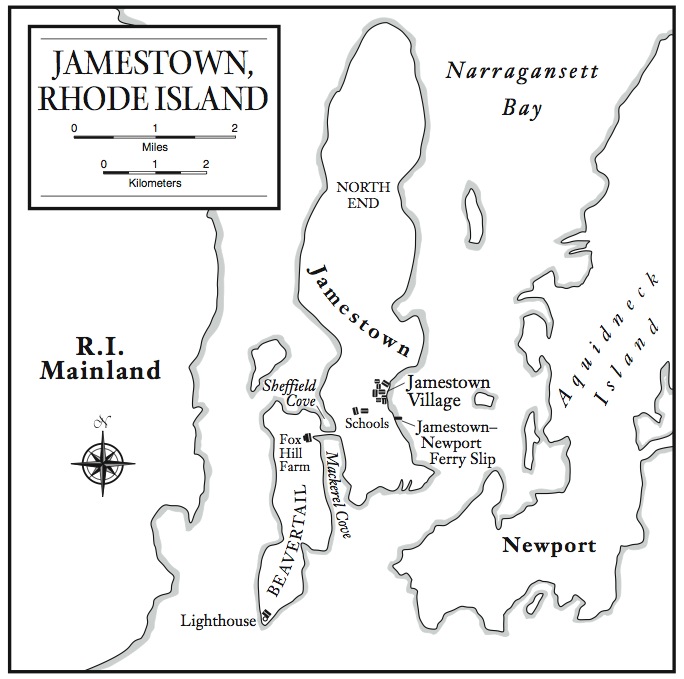

In Jamestown the wind was kicking up as Norm Caswell began his afternoon bus run. The Caswells had lived on the island long enough to know every cove on the coast and every quirk in the weather. Norm and his brothers fished the bay waters every season. They had ridden out squalls, northeasters, and line storms in their thirty-foot skiff. Before the twenty-first, Norm would have told you that nobody knew September gales better than he did.

Caswell usually made two trips on his afternoon run. He took the kids who lived on the north end home first, then looped back to pick up the Beavertail group. This afternoon, though, with a squall coming, the teachers were anxious to close up school and get everyone home. Norm piled all the kids onto the bus and started off for the north end, confident that he could beat the storm.