Sudden Sea (15 page)

In Fenwick, Katharine Hepburn was trapped inside the house with her mother, brother, a family friend, and the cook. The five tied themselves together with a rope and climbed through a dining room window. They dropped into waist-deep water. Like Scarlett escaping Atlanta, Hepburn battled her way to safety. “I slogged and sloshed, crawled through ditches and hung on to keep going somehow — got drenched and bruised and scratched.”

When the Hepburns reached high ground, they looked back. Kate’s Tara, which had endured tide and wind since the 1870s, pirouetted slowly and sailed away. “It went so quietly and in such a dignified manner, it seemed to be taking its afternoon stroll,” Hepburn remembered. “It just sailed away easy as pie and soon there was nothing at all left. Our house — ours for twenty-five years — all our possessions — just gone. My God, it was something devastating and unreal, like the beginning of the world — or the end of it.”

The day after the storm, Hepburn and her brother Dick returned to the beach. Digging in the sand where their home had stood for decades, they uncovered the complete set of their mother’s flatware and her silver tea service.

Hepburn’s affair with Howard Hughes did not fare as well as the family silver. Kate realized their romance was over when Hughes sent a planeload of fresh water instead of flying to Connecticut himself. In her autobiography, she described the end this way: “Love had turned to water. Pure water. But water. I think we really liked each other, but somehow — God sent the Hurricane of 1938.” Eventually, Hepburn returned to Hollywood and lived for several years in a cottage on Hughes’s estate. He orchestrated her movie comeback, insisting on a stellar supporting cast for the film version of

The Philadelphia Story.

After his round-the-world flight, Hughes never attempted to set any other aviation records. His idiosyncrasies gradually came to dominate his life. The Hepburns rebuilt on the exact spot in Fenwick — a larger, grander house, which the actress and her brother have shared ever since.

The Dangerous Right Semicircle

S

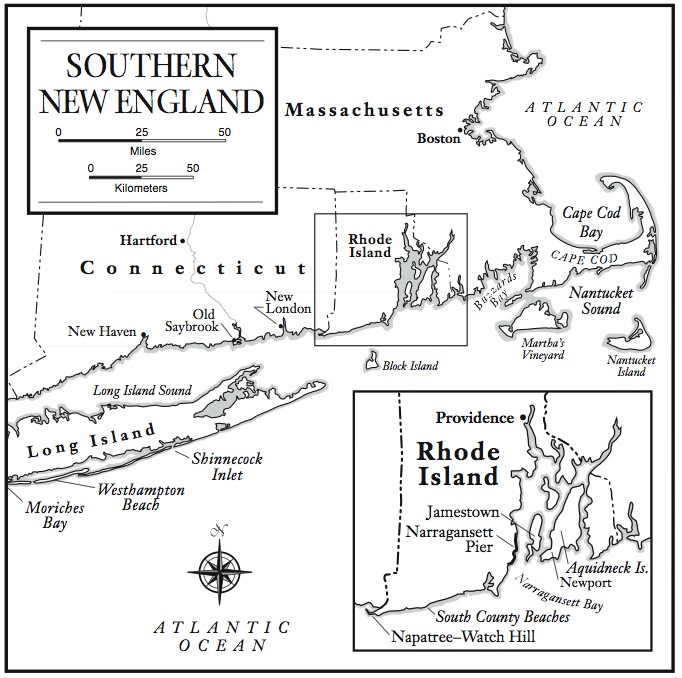

urvivors in eastern Connecticut and Massachusetts could not believe that the storm was holding anything back, but the Hurricane of 1938 saved the worst for the smallest state. Although Rhode Island is just thirty-seven miles east to west and forty-eight miles north to south, its long shoreline and geography of deep bays and low barrier beaches made it uniquely vulnerable. The Ocean State not only lay directly in the path of the hurricane’s dangerous right semicircle, it received the worst of the hurricane at the worst possible time — when the highest tide of the year was peaking.

Since colonial times, Rhode Islanders have marched to their own drummer, proudly, often defiantly. Rhode Island was the first colony to declare its independence and the last to ratify the Constitution. An adamant holdout for three years, it joined the other states only grudgingly. Rhode Islanders insist on their own clam chowder made with quahogs (it is neither creamy nor red, but steeped in its natural broth; their own hot dogs, called Saugy’s; and favorite local concoctions, jonnycakes and clam cakes, that didn’t travel well over the state line. Rhode Islanders dunk french fries in vinegar (not ketchup and drink coffee milk made with home-brewed syrup (Autocrat or Eclipse, now the same company instead of chocolate milk. It goes without saying that if it’s local, it’s the best in the world. Rhode Islanders even have their own vocabulary. They order

cabinets

instead of

frappes

or

milk shakes;

serve

dropped eggs,

not

poached;

and drink from

bubblers,

not

water coolers. Wicked,

a favorite descriptive word way before it became hip, punctuates every second sentence.

Outsiders are apt to cite the state’s size as the reason for so much contrariness, self-assertion as compensation for its smallness — it would take five hundred Little Rhodys to fill Alaska — but Rhode Islanders know better. They come by their orneriness honestly. It is the legacy of Roger Williams, the state’s founding father. “Prudence and principle” was his motto — and he lived by the latter half of it.

A charismatic Welshman, Oxford graduate, and ordained minister in the Church of England, Williams arrived in the New World aboard the frigate

Lyon

in 1631, just in time for the first Thanksgiving. He settled in the Puritan colony of Massachusetts Bay, where he was initially described as “a godly and zealous young minister.” But Williams was a freethinker moving into a tight little theocratic community that prized conformity above all virtues. From the moment he set foot in the colonies, he was out of step.

From all reports, Williams was a popular pastor. His rolling Welsh voice, his total conviction, and his intellectual daring attracted many to his sermons, but his radical notions did not endear him to the Puritan elders. Williams preached absolute freedom of conscience and religion. Thought, word, and action were rigorously controlled in the colonies, and few others dared whisper such radical opinions, let alone shout them from the rooftops.

Within two months of his arrival, the censorious Pilgrim elders had Williams on their blacklist. Although he was a thorn in their side and a cause of considerable alarm, he managed to escape banishment for several years by shuttling between Massachusetts Bay and the slightly more tolerant colony of Plymouth. Whenever a crackdown seemed imminent, he went off and lived with the Indians to learn their language. Besides an open mind, Williams’s greatest gift was a flair for languages. At Oxford, he had learned Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and several modern languages, and he applied his natural gift to mastering the native tongues. Since the Puritans considered the Indians “heathens and enemies of the Lord,” such an eccentric ambition was further cause for scandal.

In 1635 Williams was branded a dangerous heretic and banished from the colonies. The General Court dispatched an un-savory captain named Underhill to seize the young preacher and deliver him to the first ship bound for England. Word of the deportation order spread swiftly, and before Underhill could act, Williams vanished. Except for a fort at Old Saybrook (in present-day Connecticut to the south and an outpost at Portsmouth

(now New Hampshire to the north, Boston and Plymouth stood alone in a “pathless, dangerous wilderness.” The colonies were surrounded on three sides by primeval forests that stretched inland with no apparent end. On the fourth lay the mercurial Atlantic. “I was sorely tossed for fourteen weeks in a bitter winter season, not knowing what bread or bed did mean,” Williams wrote.

At that time, the Narragansett Indians were the most powerful tribe in the area that would become southern New England. They controlled the territory from Narragansett Bay in the east to the Pawcatuck River, now the boundary of Rhode Island and Connecticut, in the west. The Narragansetts rescued the exuberant preacher who spoke their tongue and brought no army. Their revered elder sachem Canonicus gave him land, protection, and grain to plant. By spring, Williams had thumbed his nose at his detractors and formed his own government-in-exile at the head of Narragansett Bay.

Of great personal charm and unquestioned integrity, Williams was liked and admired even by those, such as Massachusetts’ governor John Winthrop, who abhorred his liberal ideas. Word of his democratic anchorage where church and state were separate and even Indians enjoyed freedom of thought, speech, and conscience attracted both disaffected Puritans and new settlers from England. The oldest American synagogue is located in Newport. By 1644, when Williams obtained a royal charter, the colony had four towns, two (Providence and Warwick in the Providence Plantations and two (Portsmouth and Newport on Aquidneck Island, the “isle of peace” at the mouth of the bay.

A large wishbone-shaped estuary scooped out millennia before by a glacier, Narragansett Bay was a prime location for a settlement. The largest bay in New England, it is thirty miles long and anywhere from three to twelve miles wide. Its rocky shores offered magnificent sites for homes, and the fields beyond had rich soil for orchards and crops. In 1664 a royal commission rated Narragansett Bay “the largest and safest port in New England, nearest to the sea and fittest for trade.” Rhode Island soon became known as the “Garden of New England.” It must have been galling for the Puritans to watch a colony built on such ungodly sentiments fatten and prosper.

As the colonial trade grew, the bay’s natural inlets provided harbors for shipping, commerce, and skullduggery. Privateers and smugglers, including the infamous Captain Kidd, hid in its coves to surprise the clipper ships from Newport and Providence. Much of Rhode Island’s old Yankee money was amassed by clipper ship captains who made their fortunes in the China trade, bartering opium for tea and blue Canton, while back home in the safe harbor of Providence, their families sank deep roots into the green hillsides.

By the time Rhode Island had grown to its full, if diminutive, size, it had a 420-mile coastline, anchored at either end by a bay. To the east is Narragansett Bay, with Providence at its head and the islands of Newport and Jamestown protecting its entrance. To the west is slipper-shaped Little Narragansett Bay, with Watch Hill and Napatree. Between the two bays, from Watch Hill to Point Judith, lie a handful of seaside towns, strung along a twenty-mile stretch of coast known as South County. This is barrier beach land — low-lying strands of sand and dunes with a mix of Indian and Anglo names: Matunuck, Green Hill, Charlestown, Quonochontaug, Misquamicut, and Weekapaug. A series of similar beaches extends from southeastern Rhode Island into Buzzards Bay.

Barrier beaches are spits of shifting sands between two bodies of water, the sea on one side, lagoons and salt ponds on the other. The ocean builds the barrier beaches, and like an artist whose creation is never as perfect as the picture in his head, the sea continually sculpts and resculpts them. Pounding surf and ocean winds shape them, filling in the tidal flats with sloping dunes and dramatic bluffs, some as high as twenty feet. If you build on a barrier beach, you are toying with Nature. It is borrowed land on loan from the sea, and eventually, inevitably, the sea will come back to claim it. When a tropical intruder unexpectedly blows in, there is no more vulnerable place. Barrier beaches form a buffer zone of sorts between the ocean and the mainland. In a hurricane, they become killing fields.

The Great New England Hurricane of 1938 struck Rhode Island with a storm surge of unimagined dimensions. Like a barbarous army, it plundered the coast, gouging out beaches, leveling dunes, and rolling over bluffs, and when it had finished destroying its own handiwork, it took on human constructions. The ocean banged on doors and windows and burst through walls. It swirled into first-floor rooms and knocked down walls and stairways. Then it went upstairs into the bedrooms where families sought refuge, and chased them higher yet, into third floors and attics, onto rooftops, until there was no place to go but into the sea.

The density and force of water is a thousand times more powerful than the force of air. Under the double whammy of wind and wave, homes that had sheltered generations and weathered years of September gales folded as if they were built of cards. The sea swallowed some houses whole and smashed others to smithereens. Still others it lifted as carefully as a housewife rearranging the living room furniture and set down at a different place, sometimes a mile or more away, without splashing the milk in the creamer.

The suddenness of the storm surge was startling. Propelled by the furious wind, it came at such a speed that a man sixty feet from his front door and running allout just made it into the house. Beach residents moved fast, but the sea moved faster. What to wear? What to bring? If they took time to pack an overnight bag, grab a toothbrush or a change of underwear, find a child’s rubbers … if they ran back for the family silver or to check the gas burners, they might be wasting their last moment. A minute spent or saved could be the difference between life and death.

Many tried to flee. Families packed into cars and, pressing the accelerator to the floor, tried to outrun it. All the while through the back window, they watched their pursuer gaining on them. Others, thinking they might have to spend the night somewhere without heat, bundled into sweaters and slickers and pulled on boots to slosh through the surging water. They were dressing for certain death, because the burden of heavy clothes would weigh them down in the water.

Timothy Mee owned eight houses on Charlestown Beach and rented seven of them. On Wednesday morning he was working in Woonsocket, a mill town in northern Rhode Island. His wife, Helen, was alone in the eighth bungalow with their children, Timothy Jr. and six-month-old Jean, and their maid, Agnes Dolan. When the weather turned, Mee left work and drove to Charlestown. The Atlantic was turbulent, magnificent, and terrifying, and if Mee had been on his own, he might have stayed at the beach to watch the storm. But he was a worrier by nature, the kind of man who looked in on his children several times before he went to bed and always double-checked that the gas was off and the doors locked.