Straight on Till Morning (39 page)

Read Straight on Till Morning Online

Authors: Mary S. Lovell

Beryl with her own horse, Blue Brook,

circa

1960.

(B.M.E.)

Â

Beryl with winning owner Nairobi, 1977.

(B.M.E.)

Â

Beryl's house at Naivasha

circa

1963.

(B.M.E.)

Â

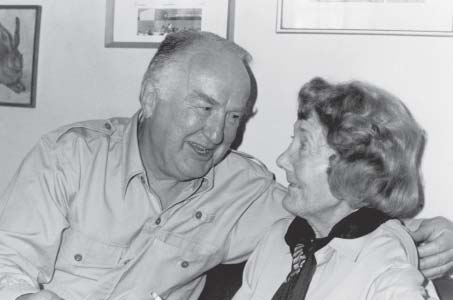

With George Guterkunst during the filming of

World without Walls,

the televised documentary of her life.

(G. Guterkunst)

Â

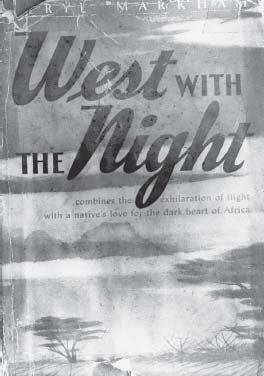

Cover of Beryl's copy of the first edition of

West with the Night

.

Â

As the condition (fibroid tumours in the womb) worsened, Beryl became increasingly perverse and her temper extremely volatile, probably because of a hormonal imbalance accentuated by her approaching menopause. âAt times she seemed almost mentally out of control, banging doors, and breaking things,' Doreen recalled. âSometimes when she sat and talked after dinner her voice would go up a tone and she would rave at us for hours about nothing in particular.' On one occasion after the Bathurst Normans had retired to bed, they heard a noise, and when Charles got up to investigate he found that Beryl had broken the sitting-room window and wrenched it off its hinges in order to get in to see them; she was incredibly strong for a woman despite her illness. On another occasion, after a row over nothing in particular, she struck Charles, but he promptly hit her back, telling her she would have to leave the farm if her behaviour did not improve. She threatened suicide and once ran away without telling the Bathurst Normans where she had gone. She eventually turned up at a neighbour's house where to the astonishment of her hosts she treated them to a tirade lasting several hours. It was all very disruptive and worrying for the Bathurst Normans, who had more or less adopted Beryl and were extremely concerned for her.

Eventually Doreen was able to persuade Beryl to see a doctor who diagnosed probable cancer of the womb, and had her admitted to hospital at once. It wasn't cancer, but the condition (probably worsened by several incompetently performed abortions in earlier years) was serious enough to require a hysterectomy, which in the early 1950s was still regarded as major surgery. âBeryl told us she hated hospitals and wouldn't stay there to recover from the operation, so the next day we brought her home and put her to bed in the cottage,' Doreen recalled. âShe wasn't supposed to be moved and she did, actually, look awful. The next morning there was a fearful racket in the yard and I looked out of the window to see my dog and a strange dog having a fight. Then Beryl's boxer dog Caesar joined in the fray. I was on my way out to put a stop to it when the door of Beryl's cottage burst open and Beryl erupted into the yard in pyjamas. She strode over to the dogs as if there was nothing wrong with her, and taking each by the scruff of the neck she hurled them aside. Then she grimaced at me, wiped her hands together as if to say âThat's that then!' and strode back to bed without a word.'

To the Bathurst Normans' dismay Beryl's behaviour showed little sign of improvement as she gradually recovered from the operation. Eventually, Charles felt he could no longer tolerate the upheavals in his home, and said Beryl would have to leave; but Doreen would not allow it, for Beryl had nowhere to go and no money. Leaving Naro Moru would not resolve Beryl's problems. Charles himself then became ill with what turned out to be an infected bile duct, which eventually required surgery. At times he felt very unwell and found Beryl's tantrums particularly trying but because Beryl had virtually become part of their family they agreed to tolerate her behaviour.

George and Victoria were then taken back to school in England as the Mau-Mau troubles grew in intensity and Charles refused to allow Victoria to stay on the farm. One day Charles and Beryl visited a local farm owned by a white hunter called Eric Rundgren

10

who was in the process of selling up. They had gone there to buy some chickens from the young Dane, Jørgen Thrane, who was in charge of the farm whilst Rundgren and his wife were away on safari.

They stayed talking, Jørgen expounding the profits that could be made from growing wheat in the area and adding sadly that he would be leaving when the farm was sold. Charles asked, âWould you come and grow wheat like that for me?' âYes,' said Jørgen without hesitation. On the drive home Beryl said to Charles, âI suppose you do realize that when that chap said Yes he meant just that?' According to Beryl, Charles looked dumbfounded but immediately made plans to see Thrane again. He wrote about it to Doreen who was in England on the âschool run'. âI'll tell you all about it when you return. I call it “last chance in Africa”â¦' the letter said. Doreen came back to find Jørgen Thrane installed, and was instructed by Charles to get to know him better and let him know what she thought. Asked to describe him at that time Doreen said

How can you describe someone who after thirty years you regard as one of the greatest friends you have ever had? I'll do my best. Jørgen had originally arrived in Kenya with two words of English â âYes' and âNo' â and ten shillings

11

in his pocket. On the recommendation of a friend he had obtained a job in the Trans Nzoia before leaving Denmark. His lack of English and Swahili got him the sack, and he arrived by way of another job at the Rundgrens where he became involved in growing wheat. The district was swarming with Danes, Charles used to call it âthe last of the Norse Sagas'.

Jørgen quickly became a friend and was delighted to be at Naro Moru. He was one of six children, the youngest of whom was Gudrun, who had gone blind at the age of thirteen but this had not prevented her from becoming a famous organist in Denmark. To obtain a farming diploma, Jørgen had worked in a plastics factory to earn the money to pay for the course. His sport was rowing and he had formerly been an inter-Scandinavian competitor. He also loved horses and riding and had owned a beautiful hunter in Denmark.

He was essentially very easy to get on with, âgemütlich' to a degree (there is no English word for this quality). Always full of laughter, we all loved him. Very shortly after he came to the farm, Charles offered him a full partnership. Jørgen had already saved a little money and this he put into the farm, with the remainder of the risk covered by Charles, and the farm was then registered as Norman and Thrane Ltd. He quickly became devoted to Charles whom he treated as a mixture of father and elder brother. He is intuitive and shrewd rather than clever, but he will work very hard to acquire any knowledge necessary to the success of a new project. To look at he is very tall and slim, very fair and with blue eyes crinkled round the edges. Jørgen and Beryl quickly developed a close relationship. Somehow he managed to provide the strength and support that Beryl always needed, and from the time he arrived at the farm, she was able to pick up the threads of her life and go on.

The oddest thing about Beryl was that although she could ride any horse, anywhere, fly the Atlantic, and was unafraid during activities such as game-spotting, over mundane things she was indecisive and needed to have her hand held, metaphorically speaking, all the time.

Doreen Bathurst Norman thought that after Clutterbuck left for Peru in the early 1920s, Ruta had filled this role, followed by Denys Finch Hatton (whom Doreen always regarded as the greatest love in Beryl's life), possibly because his detachment made him somehow unattainable. When Beryl had a âsupporter' â and this person did not have to be a lover, but just someone on whom she could trust and rely, and whom she respected absolutely â then âher insecurity took time off'. Jørgen was following in the footsteps of Clutterbuck, Ruta, Finch Hatton, Campbell Black and Schumacher, who were the major figures in Beryl's life; between them came shorter periods of supportive help from Lord Delamere, and numerous others.

Although Beryl's behaviour improved after Jørgen's arrival at Naro Moru, she was still restive. The secretarial work gave her an interest, but what she really wanted was to get back to horses. During her convalescence a friend gave her a broken-down racehorse to use as a hack. The animal âlooked like a coat hanger when it arrived. It had been overdosed with worm tablets and quite ruined for racing â or for anything else really.' It was the best thing that could possibly have happened. Beryl decided to work on the animal and in time it was not only fit but was able to race. âIt never won, but I think it managed to get itself placed a couple of times,' Doreen recalled. This episode was a turning point in Beryl's life and set her on the track of her next great triumph. She decided to start training again and there was some talk of her training for Tom Delamere whose stable was not doing too well at the time. Beryl went to Soysambu to discuss the proposal but it came to nothing and she eventually decided, with Jørgen's enthusiasm to bolster her resolve, to train publicly.

The problems were immense. Firstly Beryl had no money to buy horses and nowhere to train from. Secondly she had been out of training for thirty years, and had no current reputation or contacts. She was already approaching her mid fifties, an age when most women would not contemplate taking on a new and stressful career particularly after major surgery. Predictably, none of these difficulties occurred to Beryl â or if they did she paid no heed to them. She managed to raise £1500, the most likely sources being Mansfield, who helped her financially on a number of occasions, and Clutterbuck. Probably it was a combination of both.

At the bottom end of the Bathurst Norman property was a small piece of land consisting of a small house and twenty-five acres, which providentially came on to the market. Originally it had been part of Forest Farm but it had been sold separately, some years before the Bathurst Normans arrived. Beryl put up her capital, the Bathurst Normans underwrote a bank loan and the small farm â heavily mortgaged â became Beryl's. Twenty-five acres could never in normal circumstances have provided an adequate basis for the establishment she had in mind, but fortunately the Normans were happy for her to use some of their land, and their farm machinery and labour were at her disposal for gallops and the maintenance of paddocks. Equally important, she had the personal support of Charles, Doreen and Jørgen: