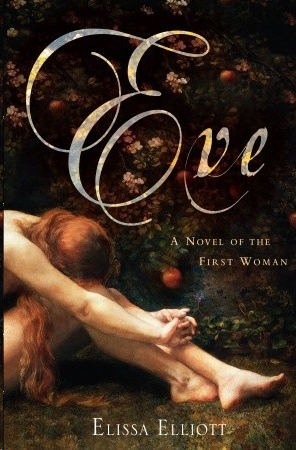

Eve

Authors: Elissa Elliott

Tags: #Romance, #Religion, #Fantasy, #Historical, #Spirituality

Table of Contents

Part 1 - Strangers in the Land

Part 4 - Strangers in the Land

For Daniel—my Adam

The world was all before them, where to choose

Their place of rest, and Providence their guide:

They, hand in hand, with wand’ring steps and slow,

Through Eden took their solitary way.

— from John Milton’s

Paradise Lost

,

Book XII, Lines 646–649

Come, my child. You heard my crying and did not wish to intrude

upon your old mother. I heard your footfalls outside my door and waited, but you did not enter. No doubt you were afraid, since I was the one who sent you away, doomed you to a life of aimless wandering with a cursed husband. My cursed son.

Closer now, let me look at you. Too many moons have passed since I saw you last. So beautiful you are, yet your eyes are restless, your cheeks are loosened like waterskins. Your shoulders curve like a sickle, and when you walk, it’s as though you are mired in a riverbed.

My child, rest, sit awhile, and listen. The day is almost done for us. The oil lamps are lit. The frogs rasp from the desert sands, and the spiders and scorpions have been brushed from the corners. The mice have been lured elsewhere, to forgotten bowls of wheat and barley. The cock will not disturb us until daylight shouts.

Where is Cain? Does he still bear the mark upon his brow?

Do you have many children, a quiver full of arrows?

You make to speak, but your lips are parched. Perhaps you need wine with a little milk? Here, take this cup and drink. I see you have come a great distance, rods upon rods, to be with me, and I am here to greet you and bless you and tell you how your presence gladdens my heart and puts a smile on my lips. A daughter can cure any ill.

I was once as beautiful as you. You would not know it to look at me, but I have lived most of my life as grass beaten down by rain, broken and trampled as you are. It is no way to live; I’ve come to know that.

Adam, your father and my lover and my friend, has returned to the earth. Your siblings are grown and have children of their own. They grew weary of my storytelling long ago, though had one of them listened, really listened, I would not need to tell it again, to you. That is how I see it: A tale needs only to be told as many times as it finds its way home.

Give me your hand. I say to your weary soul, Elohim is near to the brokenhearted, the crushed in spirit. Go ahead, cry, and breathe deep. Incline your ear to me, dear Naava.

I know that to some my name sours on the tongue and twists in the ear, but understand this: Remembrance is holy, blame is not.

Look here, look what I have kept all these years. After your bitter and rapid flight in the night, the three of us, your sisters and I, could only hunch next to the fire and press our emotions, our memories, into clay. Now they are only shards, crumbling in an old jar.

Now they are like me, tired and brittle and full of recollections.

My child, these are our lives. Even as Elohim dug up the red earth and breathed life into it, so we, also, scooped up river mud and breathed life into it.

Each one of these clay fragments tells a story.

Each one represents a season in this grand and cruel world of Elohim’s.

Listen. Can you hear them?

I came upon my son’s body by the river. The morning was no hotter

or drier than usual, but as I crossed the plains between the house and the river, the wind kicked up the dust clouds, and I had to hold my robe over my nose. Dust clung to my wet face and marked the crooked trails of my tears. Behind me, the sky was the color of lettuce. The sand chafed my swollen feet, and my groin ached with the pains of Elazar’s birth—was it just last evening I had borne him?—and my heart, oh, my hearts deep sorrow was for the travesty Cain had committed, then confessed to me like a blubbering child.

The body was not hard to find. The flies and vultures led me to him, fallen under the date palms, alongside the marshy river. His face was unrecognizable; Cain had seen to that. I don’t remember if I was sad or grieving just then. I was more astonished than anything. I had seen animals killed, their throats slashed and their viscera splayed out on the ground, and certainly there were my babies who were lost. But nothing prepared me for the sight of Abel, my precious son, as still as a rock, his head bloodied and his neck arched back, stiff, at an unnatural angle. His eyes—I realize now that it was a miracle they had not yet been pecked out!—once full of his vigor and brooding and planning, were empty. They said nothing to me. Of course, Abel had said little to me ever since he took to the fields to

tend his goats and sheep, but that is no matter. He was still my favorite. Is a mother permitted to say such things about her children?

I fell to my knees and threw my body over his. I lifted his head, cold and broken, to my breast, and cradled him there, as I had done so often when he was a baby. Fresh tears refused to come, which was strange. It was as though I had been thrown out of the Garden once again, rejected and abandoned, and, as only Adam can testify, they flowed like a river then. And where

was

Adam, my husband? Did he not care about our son, the one kissed by Elohim for his magnificent sacrifice? Or had Adam’s deafness prevented him from hearing my anguished cries when Cain told me what he had done?

Softly, I sang the Garden song into my dead sons ear. I knew he would hear it, wherever he had gone off to. He had been the only one to understand its message and allure.

Abel’s flesh was cold and clammy, and all I could remember was the vision of loveliness he was as a child—soft chubby skin folds and eyes only for me. He was the first to bring me gifts—poppies and ranunculus and clover, discarded feathers, and pebbles worn smooth by the river and carried down from the mountains. Cain would not have thought of it. He was too busy traipsing after his father—digging, planting, terracing, and experimenting with anything green.

What sorrow there is in having children! At first, they tickle your heartstrings. They linger for your words, clutch at your skirts, feed on your breath, and then one day they lurch to the edge of the nest and flutter out. They never return, and the empty space yawns impatiently, demanding more. It is a never-ending ache, one that I continued to fill as long as I was able.

The vultures hissed at me and made loud chuffing noises. They spread their mighty wings and danced about.

“Get!” I shouted, half rising and waving my arms.

They did not budge.

Where was my Abel? Where had he gone? Was he wandering somewhere, looking for his mother?

I wondered if he would weep at not finding me. I remembered Elohim’s words to Adam and me, “For you are dust, and to dust you shall return,” but still, I did not believe it, did not

want

to believe it. What good were our lives if, in the end, we simply returned to earthly particles?

To make sense of this tragedy, I shall have to go back to the beginning of that hot summer, preceded by the spring harvest and sheep plucking, when our family’s unraveling began. Unfortunately, it is always in hindsight that we see our mistakes, like a wrong color in the loom or a foreign stalk in our fields, but by doing so, I try to account for my life and change that which I can. It provides a bit of solace.

Imagine then: The sun hung low and orange on the horizon, and Naava, my eldest daughter at fourteen years, was lighting lamps in the courtyard. There was the usual bustle of the men coming in from the fields—Adam, my husband, from the orchards and Cain, our eldest son, from plowing. Adam, his robes caked with dirt and sweat, hung his arms across my shoulders and squeezed. “Wife,” he said, pecking me on the cheek. “How is my woman?” He said this laughing, as though he had said the most humorous thing, and I grinned back, glad of his presence.