Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (22 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

RISH HORSE AND DOG’S BODY

The daily diet of a seaman serving in one of Henry VIII’s ships was virtually unchanged for his descendants serving in Nelson’s navy 300 years later. It consisted largely of ship’s biscuits and salted meat, with some cheese, peas, oatmeal, sugar and butter. Although adequate in terms of calories (up to 5,000 per day) for hard work at sea, the food was often of poor quality and the diet lacking in vitamins and minerals.

From Drake’s day onwards the crew ate in groups of six to eight called messes. Each man would take his turn as mess cook and collect the day’s rations from the purser’s steward in readiness for the noon meal. The prepared food, which varied with the skill and interest of the man on duty, was taken to the galley to be cooked (each mess marked their food with a tag). The mess cook was responsible for washing up the utensils and generally cleaning the eating area after the meal. He was entitled to an extra tot of rum for his trouble.

The mess cook carved and served the meal. To ensure fairness, one of the other men was blindfolded, a portion of the meat was carved, the blindfolded man called out a name and the portion went to that man and so on, until it was served. However, this system was not always followed, and younger mess members were sometimes bullied and deprived of the best victuals by older men.

The ship’s cook was no trained culinary master. Usually a disabled seaman, often having suffered an amputation, his main role was to ensure the galley was run efficiently and that the boiling coppers were cleaned daily.

Sailors had their own names for certain items of their diet:

Cornish duck | pilchards |

Dog’s body | pigs’ trotters with pease |

Crowdy | watery porridge |

German duck | boiled sheep’s head |

Lobscouse | stew made with pounded biscuits |

Irish horse | salt beef |

Canned meat and vegetables was first tried out in the Channel Fleet in 1813. It became known as bully beef because it was adapted from the French recipe for

boeuf bouilli

(boiled beef). In 1866 the Victualling Office itself began to manufacture it. Unfortunately, the very next year a famous prostitute named Fanny Adams was murdered and her body cut up into small pieces. The word went around among seamen that what the authorities were providing was Sweet Fanny Adams.

Ship’s cook by Rowlandson

Ship’s cook by Rowlandson.

LIFELINE – a source of salvation in a crisis.

DERIVATION

: in foul weather, ropes were rigged fore and aft along the deck of a ship to provide a secure handhold for a sailor to grip to prevent him from being washed overboard. If conditions turned extremely nasty a sailor would grab the line and wrap it around his arm for extra security – then hang on for dear life!

R

RUMBUSTION

Since the early days of sailing ships the most readily available liquids to take on voyages were water and beer, both of which could only be stored for a short time before they became unpalatable.

Vice-Admiral William Penn’s fleet conquered Jamaica in 1655, and it was here that rum, or rumbustion, was first issued on board ships of the Royal Navy. Rum was also called rumbullion, kill devil, Barbados waters and redeye.

Rum has the advantage of keeping well, even improving with age. When abroad captains of ships were allowed to replace beer with fortified wine, sometimes brandy, but neither was available in the West Indies. Rum was, however, and it became a popular drink ration in this part of the world, even though the Victualling Board back in England had not officially sanctioned its use.

From 1655 well into the eighteenth century the issue of rum very much depended on individual captains. In 1731 it was officially decreed that if beer was not available then each man was entitled, daily, to a pint of wine or half a pint of rum or other spirits.

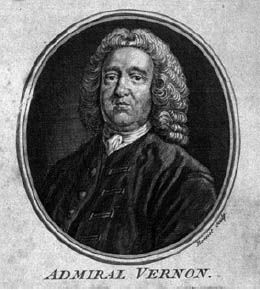

In 1740 Admiral Vernon (nicknamed Old Grogram because of the boat cloak he wore made of that material) ordered that the rum issue be diluted 1:4, and thereafter the drink was called grog. He talked of ‘the swinish vice of drunkenness’.

By 1793 the dilution was usually 1:3. From Vernon’s day until the end of the Napoleonic Wars two issues of grog per day remained the custom whenever beer was unavailable. But the use of rum gradually became more widespread, as did the issuing ritual. The ship’s fiddler played ‘Nancy Dawson’, the signal for the mess cooks to repair to the rum tub to draw rations for their messmates. This was always done in the open air because of the combustible nature of rum.

Rum was a currency aboard ship, with special terms for various amounts of the spirit. Gulpers meant one swallow, but as much as you could drain in one go; sippers, a more genteel amount as suggested by the name; and sandy bottoms, the entire tot.

The American Navy ended the rum ration on 1 September 1862, but the practice continued in the Royal Navy for over a century. Friday 31 July 1970 saw the last issue and became known as Black Tot Day.

The First Sea Lord issued this message to the Royal Navy:

Most farewell messages try

To jerk a tear from the eye

But I say to you lot

Very sad about tot

But thank you, good luck and good-bye.

‘

‘Old Grogram’ gave his name to the sailors’ favourite tipple

.

S

ET UP FOR LIFE

Prize money was a lottery; while the odds of great wealth were very slim, fortunes could be made. The origins of prize money lay in the Cruisers and Convoys Act of 1708, which gave practically all the money gained from the seizure of enemy vessels to the captors ‘for the better and more effectual encouragement of the Sea Service’. In some ways prize money was unfair – all ships within sight when the capture took place were entitled to equal shares. And the admiral under whose orders the ship sailed was entitled to a share even if he was nowhere in the vicinity.

The following distribution scheme was used for much of the Napoleonic Wars, the heyday of prize warfare:

One-eighth went to each of these groups – flag officer; the captains of marines, lieutenants, masters, surgeons; lieutenants of marines, secretary to the flag officer, principal warrant officers, chaplains; midshipmen, inferior warrant officers, principal warrant officers’ mates, marine sergeants. Two-eighths went to each of these groups – captains; the rest. The latter included all the seamen, many hundreds of men.

The taking of prizes could be very lucrative. The record haul came from the capture of the treasure-carrying Spanish vessel

Hermione

in 1762 by two British frigates. When the pay of a seaman was less than a shilling a day, the prize money in this instance to each seaman of £485 (nearly 35 years’ salary for a few hours’ work in the afternoon) promised to set them up for life – if they didn’t spend the proceeds on too many rollicking celebrations ashore. Their share pales into insignificance, however, beside what the two captains responsible were awarded: £65,000 each, or over £8,000,000 in today’s money. The treasure was conveyed from Portsmouth to the Tower of London in 20 wagons and was greeted in the capital by a troop of light dragoons, a band and joyous spectators.

After taking a number of rich prizes Captain Thomas Cochrane in HMS

Pallas

famously sailed into Plymouth with three five-foot-high gold candlesticks at the masthead. Among the other naval officers who amassed enormous sums were Hyde Parker, who realised £200,000 when he was in command in the West Indies, and Peter Rainier and Edward Pellew, who accrued around £300,000 each during their careers.

It was usually only frigates that took prizes. Ships of the line were too ponderous to be able to capture the smaller ships that carried treasure. However, ‘gun money’ and ‘head money’ was paid on larger captures, which went some way to compensate.

Nelson did not fare well with prize money. This was not so much bad luck as the irony that, largely due to his genius, Britain achieved mastery of the sea – and few enemy ships dared to sail.

The distribution of prize money to crews of ships involved persisted in the Royal Navy until 1918.

The magnificent Shugborough Hall in Staffordshire, built with the fortune Admiral Anson amassed from prize money

The magnificent Shugborough Hall in Staffordshire, built with the fortune Admiral Anson amassed from prize money.

T

HE SILENT SERVICE

When Napoleon surrendered to HMS

Bellerophon

shortly after the Battle of Waterloo he remarked, as the ship was getting under weigh, ‘Your method of performing this evolution is quite different to the French. What I admire most in your ship is the extreme silence and orderly conduct of your men. On board a French ship everyone calls and gives orders and they gabble like so many geese.’ Then, before he left

Bellerophon

, he said, ‘There has been less noise in this ship, where there are 600 men, during the whole time I have been in her than there was on board the

Spervier

[a French frigate] with only 100 men in the passage from Isle d’Aix to Basque Roads.’

Later, on the voyage to the South Atlantic, Napoleon was also struck by the way the crew of HMS

Northumberland

, taking him to exile in St Helena, performed their duties in a similar manner. This was not unusual, however. Work in the Royal Navy was generally performed in silence.