Staying True (10 page)

Mark’s friend Senator John McCain, who was quietly beginning his run for president, visited our home the next day, a Sunday. Mark had a group of about thirty men for lunch to meet him. I served sub sandwiches from the deli on paper plates, about all I could handle at that stage in my pregnancy. Mark prompted McCain to tell stories from his time as a POW and gathered our boys to listen. The hubbub of boisterous political talk died down as the whole group leaned in to hear his tales from the Hanoi Hilton.

One story that particularly moved Mark and me was about McCain’s cellmate, Mike Christian. Every day, no matter what horrors he and the other prisoners had endured, they rose to pledge allegiance to the flag. Mike Christian had sewn a replica of the flag onto his shirt for the soldiers to look at when they pledged. When the guards discovered it, they ripped the flag off his shirt and beat him severely. Upon return to his cell, he quietly began sewing on another flag. He was, quite literally, willing to die for his flag and his country.

Mark and I drove to the hospital the next morning and Blake arrived easily, another healthy baby. Mark and I decided to give him the middle name of Christian, in honor of the patriot-soldier in McCain’s story. From the first, Blake seemed calm and steady, something that still serves him well as the youngest of this brood. Mark then caught the mid-morning flight to DC in time to vote in Congress. Having these kids was so easy for Mark, I think he would have been happy with ten sons, but the pregnancy and birthing of them all was clearly less easy on me, and we had decided that these four healthy blessings were just enough. The next day I was scheduled to get my tubes tied.

As I was wheeled in for surgery, the nurse asked me why I didn’t have anyone with me for support. I was surprised at her question. It hadn’t really occurred to me that I would need Mark there for the surgery. What would have been his role? He could wring his hands and worry about my progress from Washington just as well as he might have from the waiting room. In any event, I told her my husband had been with me the day before, but he’d gone back to work. Maybe her question was perfunctory, or maybe she truly was surprised to find me alone. Either way, I can see now that our circumstances were unusual. Somehow, I had become perfectly accustomed to managing alone. My independence gave Mark tacit permission to leave that day, and, I can’t help but wondering, later as well.

Late in the 1990s, Mark was nearing his last term in Congress and his anxiety about what would come next in his life was active on all fronts. Impressed by the dedication and professionalism of the military he saw through his activities on the Hill, he began to regret that he had never served. He lamented the increasing disconnect between the rights that go with being an American and the responsibilities of citizenship. So, during his last term in Congress, he enlisted in the Air Force Reserves. In addition to seeing this as a responsibility of citizenship to participate, he also wanted to set a good example for our boys. By the time the military accepted Mark, he was already running for governor, but he decided to honor his commitment, and I was proud of him for that decision, even as I understood that he would now have even fewer weekends at home for the family.

Perhaps part of Mark’s anxiousness was also because he was approaching forty, and he wasn’t taking it very well. By that point, ten years into our marriage, I was accustomed to his restlessness and list making, but the confluence of passing that age marker and ending his time in an important job made this transition more fraught than others had been.

Mark’s zest for living life to the fullest comes, I think, from his fear of dying, and of dying young in particular. I think this feeling overcame him as a young man when he quite literally put his father in the ground. He often spoke about how short life is and how he needed to fill every minute. Mark is not alone in his point of view, of course, but the worry that stuck most in my mind was his sad feeling that past the age of forty he would have “no more good summers.” As someone who treasures every day, every season, this statement was and is unimaginable to me. On the brevity of life, we both agree. The difference is how we chose to spend our time. I wanted to savor each moment while the boys were young and he clearly wanted not a moment to sit still.

As a result, the small signs that he was starting the inevitable process of slowing down unnerved him. When his back hurt or his sore knees kept him from running ten miles at the same pace he had when he was younger, he took this as evidence of his approaching death. He brushed aside my suggestions that he adjust his exercise pattern to suit his age. He was going to fight this at every turn, never giving in to the inevitable.

He’s not alone in this fruitless struggle. Our culture celebrates the hardness and vigor of youth, the edge that comes with it, and seemingly has no time for its opposite. But I believe in what Marcus Aurelius said: “There is change in all things. You yourself are subject to continual change and some decay, and this is common to the entire universe.” I feel strongly that the best way to age is not to fight it and the change that comes with it. Rather, I try to embrace it and grow through it.

Whatever our differences though, his concerns were genuine and, I have to admit, the inspiration for a great fortieth birthday party.

Naturally, I threw him a surprise party. He thought he was going to give a formal speech at Middleton Plantation but on his way to the building in which he expected to speak, his friends and family emerged from the gardens all dressed in funeral wear. Everyone wore black, the women were handed lace veils, and someone even came dressed as the grim reaper. The special feature of this celebration wasn’t presents. Nearly everyone there had written a eulogy for Mark. His worst nightmare—that he would die at forty—became the inspiration for a memorable celebration that, I hoped, showed him how much he was loved.

Mark was a good sport about the party, though perhaps the rest of us thought it was a lot funnier than he did. In trying to gently—or not so gently as the case may have been—rib him about his worry, I hoped to relieve him of it. I wanted to show him that life was not anywhere near over and that he was not now on the path to decline. I wanted him to see that there was much fun to be had then and ahead.

EIGHT

I

EXPECTED THAT IN 2000, WHEN MARK KEPT HIS CAMPAIGN PROMISE not to run for a fourth congressional term, he would return to a smaller-scale life with me and the boys. I believed Mark would be ready to return to working in real estate and be even more successful for all the knowledge he gained in Congress and all the powerful and important contacts he had made while serving there. All of this, combined with more time with me and the boys, would give him, I hoped, many more ways to quantify his accomplishments, to feel successful and finally appreciate that his life had meaning.

We never really had the time to find out. It wasn’t very long before people from across our state started to urge Mark to consider a run for governor, probably one of the hardest jobs in politics. As with his first run at Congress, Mark’s appetite for a challenge was whet at the prospect of seeking a job where it would be difficult to get elected. He would yet again have to win a tough primary against six other Republicans and after that, he would face a well-funded Democratic incumbent, Jim Hodges. He was also energized by the idea that if elected, it would also be a challenge for him to succeed.

South Carolina state government operates under a truly archaic system. After the Civil War, politicians worried that a heavily black constituency would some day elect a black man as governor. With that in mind, then-governor Ben Tillman led the effort to change the state constitution dramatically, stripping the governor of most of his powers. The legislature, a variety of constitutional officeholders, and various un-elected boards and commissions have largely run the state ever since. The governor is often the first to be blamed when he can’t fulfill his promises, even though the mechanism of state government is arranged in a way to block him at almost every turn.

Mark spoke with advisers and consultants and friends about whether or not to run. The more people he talked to, the more excited he became about the possibility of making real change. Instead of accepting the idea that he would be working within a highly restricted environment, he wanted to run on a pledge to reform the government and to bring fiscal responsibility, common sense, and a businesslike approach to all the affairs of our state. He saw the need for a governor to look out for the interests of the state as a whole, as a chief executive should. Just as important to him was preserving the aesthetic look and feel of the state. He had strong feelings about protecting open space, keeping rivers pristine, and saving forests. He wanted to avoid the kind of overdevelopment seen in South Florida. This was and still is a rather rare stance for a Republican. With these as his issues, we calculated that there was a slim chance he would win.

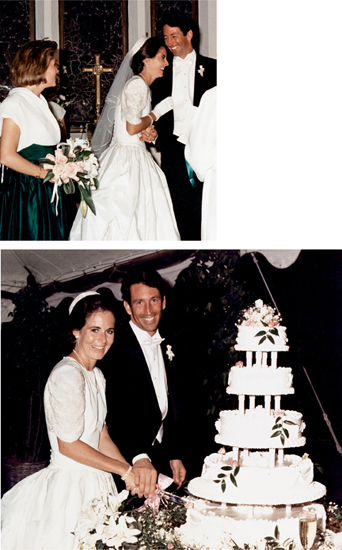

Our wedding day, November 4, 1989

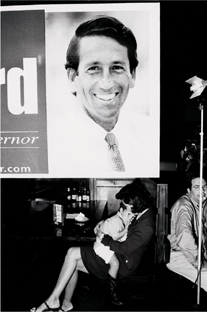

Past bedtime, primary night, 2002

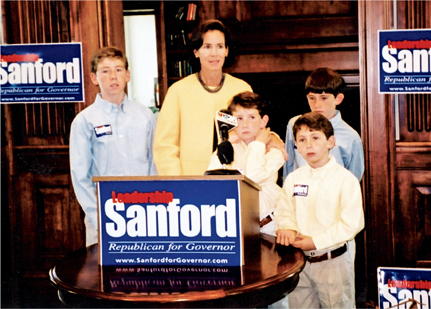

Campaigning was always a family affair

.

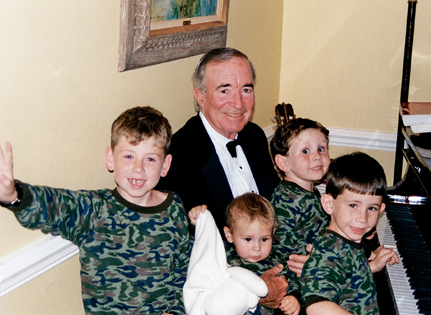

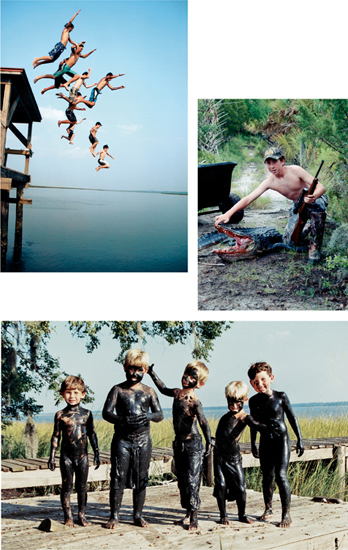

Boyhood fun at Coosaw, the Sanford family farm

Blake meets President George W. Bush

.

Mark’s swearing-in for his second term as a U.S. Congressman, January 1997

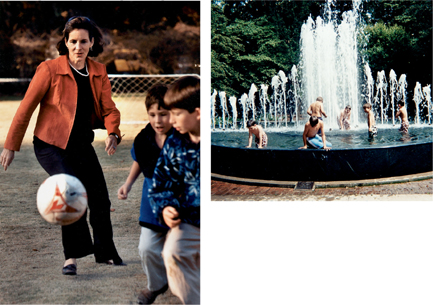

Fun at the Governor’s Mansion

More fun with friends, celebrating my fortieth birthday at the Mansion