Stars of David (20 page)

One could say that, thanks to Carrie Bradshawâher character on

Sex

and the City

âshe created a new archetype. “I don't know that anything's changed,” she disagrees. “I think I've had luck because I've found parts and obviously more recently, specifically

a

part. But Carrie Bradshaw is clearly not a Jew. So that character didn't disprove the bias that beauty is incompatible with ethnicity. I don't know if there's a ripple effect for me professionally or not. And I don't pay too much attention to it because, frankly, there was a period in my career years ago when it stopped mattering to me that a studio executive didn't think I was pretty. Because I couldn't let it. I hadn't started off with a career in which that mattered and I knew that that wasn't what my career was going to be.”

Didn't she have a moment of wishing she was the classic American beauty? “Yes, I did have a moment. I remember pretty vividlyâbecause I actually articulated it at the timeâI said, âThis is really frustrating because I'm always playing the cerebral best friend of the pretty girl.' Now, what I didn't mind about that was those were generally the more interesting parts. But it's frustrating to not be considered attractive by men who make decisions. That's what's hurtful. It's not the quality, necessarily, of the role; it's the personal ego stab that is hurtful. And you just figure out whether you have the constitution to continue. That's why I think my parents were very against me working in television and film. I think they thought that in the theater, beauty has broader parameters. My parents saw that it was when I got involved in movies that my feelings were hurt.”

But did she view those slights as related to her being Jewish? “I saw it as an ethnicity issue,” Parker replies. “I thought if I had straight hair and a perfect nose, my whole career would be different. And I

still

feel like, when I walk on the set of a movie or a television show, and my hair is straight and all the guys say to me, âWow, you look so pretty,' I always jokeâif I know them really wellââYou're an anti-Semite!' Because I just feel it's a little stab at the Jews. I always feel that people think that straight hair is pretty and curly hair is unruly and Jewish. I think it's anti-ethnic.”

I'm talking to Parker before she starts taping the last season of

Sex and

the City

, and I'm curious about the show's explicitly Jewish character, Harry GoldenblattâCharlotte's paramour. (At the time we spoke, Harry had told Charlotte he couldn't marry someone who wasn't Jewish and she was considering conversion.) “We live in a city that's full of Jews,” says Parker, who is also the show's executive producer. “The fact that we haven't dealt with it more and also didn't do better fleshed-out Jewish characters bothered me,” Parker says. “And I still worry that Harry Goldenblatt is too clichéd. That's the problem with being a man on our show. It takes time for dimension to come. We have this great actor, Evan Handler, and he's really sexy and smart and I'm excited about the potential of that. But I think we have to be careful that he doesn't become the false cliché of the loud, boorish Jewish lawyer who's aggressive; that he is dignified and interesting and smart and sexy and witty and flawed and all the things that make any guy interesting. I'm excited about it, but I hope we do it well.”

In other words, if they do it poorly, it could be bad for the Jews. “If I watch a television show about somebody and there's a Jew on thereâI don't mean fiction, I mean realityâand there's a guy on there named Goldfarb and he's a jackass, I'm like, âYou're bad for the Jews.' It's one more excuse for bigots to say, âLook at the Jews.' And I'm very protective that way. I'm very ashamed of stereotyping and one person doing a great disservice to millions.”

A couple pass our table wheeling their newborn in a carriage, and Parker comments on how cute the baby is. She chats easily with these strangersâthey clearly recognize her despite her pulled-back hair and lack of makeupâand it's an unremarkable conversation, like any other between new parents and a mother-to-be from around the neighborhood. It occurs to me that Parker is not just on the cusp of childbirth but of all the child-rearing issues that follow; she realizes it will be up to her to shape this new Broderick's identity, when she's still not quite sure of her own. “If there was a temple I could go to,” Parker says, “to get guidanceâcounsel of some kind, or just a place to sit and contemplate, whatever that means for me . . . If there was a place where you could come in and they say, âThis is what we're going to talk about today and let me put it in context for you and see whether it applies to you or not,' and hear great music and be with people who are like-minded, I think you'd have a much more growing population of people who practice the Jewish faith.”

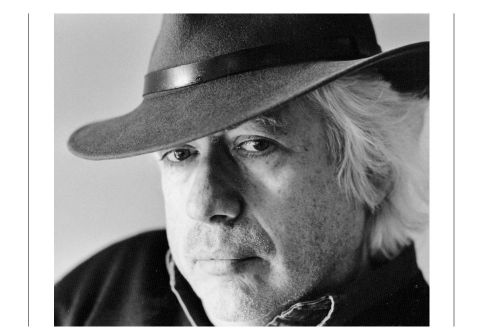

Leon Wieseltier

LEON WIESELTIER PHOTOGRAPHED IN 2005 BY JILL KREMENTZ

ONE OUT OF EVERY FIVE PEOPLE I talked to about this book said, “I assume you're talking to Leon Wieseltier.” One prominent magazine editor referred to him as “The Grand Poobah of Judaism”; others called him simply “Super Jew.”

The literary editor of

The New Republic

for the last twenty-one years, Wieseltier is, in his spare time, a rumpled encyclopedia of Torah commentary, Jewish philosophy, and Talmudic law. He is fluent not just in Hebrew, but in libraries of obscure Jewish texts. His book

Kaddish

was a chronicle of the yearâ1996âthat he spent going to synagogue the required three times daily to say kaddish for his father. He excavated, it seems, every conceivable discussion from every imaginable rabbi who ever had an opinion, all in the effort to make sense of this one prayer for the dead. A fifty-three-year-old graduate of Columbia, Harvard, and Oxford, Wieseltier is also the author of

Nuclear War, Nuclear Peace,

and

Against Identity

, and has written more essays and sat on more panels than it would be possible to enumerate.

I meet him in his Washington office at

The New Republic

âa sterile space which he's managed to make a little scruffier thanks to haphazard stacks of books on the carpet, couch, and bookshelf and careening heaps of papers on his desk. He's wearing jeans and cowboy boots; his trademark Einstein-like thatches of white hair are appropriately unkempt. He turns off his Mahalia Jackson CD so that it's quiet enough for my tape recorder, and he seems genuinely startled that I actually finished

Kaddish

, which even he refers to cheerily as “my turgid tome.”

Some warned me that Wieseltier would be disdainful of my ignorance in Judaic matters, but I didn't find that to be true: rather, he's disdainful of Jewish ignorance in general. Nothing personal. “I think the great historical failing of American Jewry is not its rate of intermarriage but its rate of illiteracy,” he says. “I can go on for many long hours about this. The amount of Judaism and the Jewish tradition that is slipping through the fingers of American Jewry in times of peace and security and prosperity is greater than anything that has ever happened in the modern period anywhere. It is a

scandal

. Now what I'm not saying is that there should be more believing Jews or more belonging Jews; this is a free country. We believe in freedom; people can think and do what they want. The problem is that most American Jews make their decisions about their Jewish identity knowing nothing or next to nothing about the tradition that they are accepting or rejecting. And a lot of American Jews

accept

things out of ignorance, too. The magnitude of American Jewish ignorance is so staggering that they don't even

know

that they're ignorant.”

I tell him he sounds judgmental. “I judge it very harshly,” he agrees. “I loathe it. Because we have no right to allow our passivity to destroy this tradition that miraculously has made it across two thousand years of hardship right into our laps. I think we have no right to do that. Like it or not, we are stewards of something precious; we are custodians, trustees, guarantors. We inherit the language in which we think, we inherit most of the concepts that we use, we inherit all kinds of habits, and one of the things we inherited is this thing called the Jewish tradition.”

He brings to mind two lines in his book,

Kaddish

, which stuck with me:

“Do not overthrow the customs that have made it all the way to you.”

Also,

“Sooner or later you will cherish something so much that you will seek to preserve it.”

But many of the people I've spoken to say they're turned off by the amount of time observance requires, the rigors of ritual. “Come on,” he interrupts me. “That is a miserable excuse. We're talking about people who can make a million dollars in a morning, learn a backhand in a month, learn a foreign language in a summer, and build a summer house in a winter. Time has nothing to do with it. Desire, or the lack of it, has everything to do with it. It's about what's important to people. We're talking about intelligent, energetic individuals who master many things when they wish to.”

That said, he has capacious sympathy for someone who engages the tradition, but then decides to forgo it. “I don't mind when Jews tell me it's not important to them. I feel sad, but they have a right to decide it's not important to them. That is the risk you run in living freely, and we should be happy to run that risk. Who would not prefer the danger of ignorance to the danger of extermination? But I would much rather people say, âI don't care to be Jewish anymore.' The bad faith of the noisily faithful makes me crazy.”

He derides a kind of Jewish identity that might be described as Judaism Liteâan identity tied to ethnicity, not education. In other words, Jews who “feel” Jewish because of a tune they remember, a cheese blintz, or a visit to shul twice a year. “Owing to the ethnic definition of Jewish life, there has occurred a kind of internal relativism among all things Jewish,” he says. “If we're just a tribe, if we're just an ethnic group, then all of our expressions are equally valuable, they all delightfully express what we are. âI like Maimonides, you like knishes, but we're Jews together!' Right? The philosophy, the food, it's all different ways of being Jewish. But if you invoke the old Jewish standard, the traditional standard, all this falls apart.”

And that standard is? “The standard is

competence

,” he answers. “The standards by which Jews should be judged are not

American

standards; they are

Jewish

standards. That is to say, if one is making judgments about the quality of Jewish identity of individuals or groups, that the criterion has to be taken not from the society in which we live but from the tradition that we have inherited. And that's where I think Jews are going to be found to have been criminally negligent.”

But why? How does he explain why so many people essentially dropped the rituals that used to define being Jewish? “Whereas American society does require the thing we call âidentity,' it doesn't require that the identity be religious and it doesn't require that the identity be thoughtful,” Wieseltier answers. “More so than it's ever been before, the ethnic or tribal dimension of Jewishness has been brought to the fore in this country. Especially since the ethnicization of American life since the late 1960s. So it is very possible in this country, where you are expected to be a hyphenated individual, for the non-American side of the hyphenâin this case the Jewish sideâto be entirely an ethnic or tribal or biological sensation of belonging. That's enough for Jewish identity, American style.

“American Jews, like Americans, have a very consumerist attitude toward their identity: They pick and choose the bits of this and that they like. They ornament themselves with these things, they want to bask in the light of these things . . . Most American Jews don't see identity as an enterprise of labor, a matter of toil. It's something automatic that confers upon you a certain status. As I say, a form of luck.

“So in America now it is possible to be a Jew with a Jewish identity that one can defend and that gives one pleasureâand for that identity to have painfully little Jewish substance. The Jewish substance of Jewish identity is not necessary, or it is minimally necessary.”

I tell him that many of the people I'm talking to feel great pride in being Jewish, whether or not they're students of Judaism. “Generally in American Jewry, pride exists in inverse proportion to knowledge. So you will often find that the more learned or knowledgeable Jewish individuals are, the less strident and hoarse with self-admiration they tend to be. And the ones who know very little are looking for anti-Semites everywhere, because they need enmity to sustain their Jewishness. (It doesn't matter that sometimes they find it. We were never Jews because there were anti-Semites.) They think that the best way to express Jewishness is by fighting for it. And so in this way pride does the work of knowledge, sentimentality does the work of knowledge.”

So when he says that Judaism has failedâ “Noâ” he stops me. “Judaism hasn't failed. The Jews have failed Judaism.” But those who taught Judaism failed somewhere along the way, too, it seems, if there are so many disaffected people. “Yeah, I think that's true,” Wieseltier concedes. I venture that if all the bored temple-goers had had someone to turn them on to Jewish traditions and texts, they mightâ “But you know what?” Wieseltier breaks in. “You have to want to be turned on. That's like saying, âThere's no point in going into the record store, because almost all the records in there are terrible.' But you go into the record store because there's one record you really really dig. I mean, nobody ever didn't walk into a record store to buy a Charlie Mingus record because there was a Keith Jarrett record for sale, too. Again, it's all about what's important to you. It's about motivation and will; about one's expectations of oneself, about what makes the world tingle for you. It's about the tingle.”

Wieseltier certainly hasn't lost the tingle, even though he did lose the Orthodoxy with which he was raised. (The son of Orthodox Eastern European parents, he attended Yeshiva of Flatbush.) One day, he walked away from all of it. “I was alienated from shul for lots of reasons,” he says, “and I had philosophical problems with my picture of the world and I resolved that I would not go through my life without food, wine, or women.”

He explains why those pleasures were off limits: “I was an Orthodox boy. I wasn't allowed to put my hands on girls or have a good bottle of red. I decided for reasons of personal hunger and philosophical perplexity and real alienation from the synagogue that I had to wander.”

Was there literally one precise day when he stopped living by the rules? “There was a day I took my yarmulke off in my senior year of Columbia College,” he answers. “And then my first violation of the shabbos was a phone call to Lionel Trilling. And my first cheeseburger was at a Patti Davis show at CBGB's. And my first cheese pizza was at V & T's. I remember that Art Garfunkel was sitting at the next table.”

How guilty did he feel? “It depends when and where. There's also enormous pleasure associated with sin, as you may have heard.”

But his internal religious clock was unshakable. “Even when I was allegedly gone, I always knew that Friday night was shabbos. I always knew that, when I was eating something I shouldn't eat, something I shouldn't eat was what I was eating. I was never indifferent to it; I was never dead to it.”

He said his parents were not dismayed. “My parents knew how much I loved the tradition and they saw that I was devoted to it intellectually. They saw that the whole way. They were a little perplexed about how one could be so ardent a Jew and still live at such a distance from religious practice. They were perplexed. But it would have been harder for them if I had started my literary life with essays about, say, Mallarmé, and not with essays on Jewish subjects. So even if they were perplexed, they knew their son's Jewish heart, they had confidence in it, and they were right. I may have been a weird or troubling case, but I never left. I could never leave. It was a matter of honor, but also it was a matter of love.”

Love?

“I have an erotic relationship with Judaism. I really do. Judaism is the instrument that opens up the world for me. The world doesn't open up Judaism for me. The history of the Jewish people is one of the greatest human stories, obviously. So if you go and study Jewish history, you can't do it just to study about the story of how this magnificent people finally climaxed in the birth of yourself. It's not about, âHow did I get to be me?' It's about what human experience is like and what are the extremes of human experience, internal and external. That's what Jewish history is about because of what happened to Jews.