Stars of David (38 page)

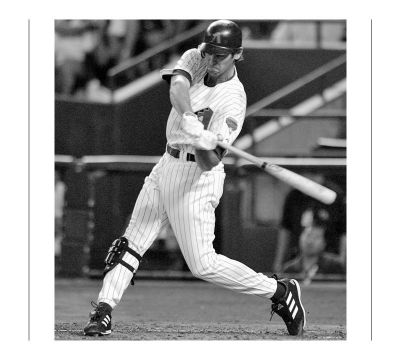

Shawn Green

COURTESY OF ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS

MOST OF THE PEOPLE I INTERVIEWED for this book say they are rarely, if ever, asked about being Jewish. Arizona Diamondback Shawn Green, on the other hand, is pummeled with the question. That's because he's unique: a Jewish baseball star.

There have only been roughly 140 Jewish players in major league history, and just two legends: Sandy Koufax and Hank Greenberg. Green draws attention not just because of his Jewishness but because it matters to him. So much so, that in 1999, when he was deciding which ball club to join after his triumphant run for the Toronto Blue Jays, one requirement was that the home city have a significant Jewish population. “I wanted to play in a place that had a large Jewish community because I wanted to be able to have an impact,” says Green. (He opted to sign with the L.A. Dodgers and is still a member of that team at the time we speak.)

An imposing six-foot-four, Green is talking to me in his uniform, standing outside the visitors' locker room in Toronto's stadium, where the Dodgers are about to play his former team, the Blue Jays. It's loud and echoey, but I can see he's used to doing interviews this wayâstanding up, on the fly. “L.A. was a perfect fit, since I'm from there,” he says. “And it has a large Jewish community. Toronto did, too.”

Raised in Los Angeles, Shawn David Green, age thirty-two when we met, has the distinction of having signed the largest contractâin total valueâin baseball history at the time, 1999: He was promised eighty-four million dollars over six years. When this left-handed outfielder and first baseman was traded from the Jays to the Dodgers, he had just completed a spectacular season: 190 hits for a .309 average, 42 home runs, 123 RBIs, and 20 stolen bases in 27 tries. The year before, he stole 35 bases and hit 35 home runs.

As Green rose in stature, his religion was often the story. The

Washington Post

blared,

“An Heir Apparent Worthy of Hank Greenberg; Blue Jays Star

Green Is Taking Baseball by Storm.”

A headline in the

Forward

read,

“Next

Boychik of Summer Reignites Koufax's Flame.”

I remind him of something he said once: “My being Jewish separates me from most players and it will separate me for my whole career.” Green nods. “When I'm done playing baseball, for the people who do remember my careerânot that it's going to be Barry Bonds's careerâbut at the end of it, people are going to remember me as, âOh yeah, he was a Jewish ballplayer.' Everyone has a label, and mine is pretty specific.”

He doesn't shirk it. When he played for Toronto, he agreed to speak to countless Jewish organizations and fielded many Passover and bar mitzvah invitations. “One of the team doctors is Jewish and a friend of mine, so I would go with him to shul. And I guess the word kind of got out.”

He is still sought after by Jewish groups in every town he visits. “I have a little bit extra on my plate when it comes to going to different cities because of all the Jewish newspapers and organizations. I try to do those interviews and meet with everyone, but I try to do them at the stadium rather than go all over God's creation.”

I wonder if he ever feels it's a burden, being the “Jewish sports star,” when he might just want to play ball. “I think it was a burden until I learned how to say no,” he replies. “Because you can only do so much. During the season, it's really hardâit got to the point where, in every city I went to, there was a Jewish community center or some Jewish organization that wanted me to come and make an appearance or do something, and I just had to say no at some point. Otherwise my life is just baseball and making appearances and that's an exhausting way to live.”

His father, Ira Green, who trained his son from the age of three, told the

Los Angeles Times

in a 2000 profile of his son headlined “Hebrew Natural” that he was weary of the religious focus. “I wish the whole thing would die down a little,” he said. “Can't writers just think of Shawn as a great player and not a great Jewish player?”

However saturated Green's family may feel, Green knows he's a role modelâespecially for kidsâand he takes that function seriously. “I missed a game for Yom Kippur in 2001,” he says, referring to his well-publicized decision to sit out the season's final home game, against San Francisco. “I just thought it was the right thing to do. At the time, we were in the pennant race, so it was a big game.” Obviously this echoes former Dodger Sandy Koufax's momentous decision in 1965 to sit out the first game of the World Series against the Minnesota Twins because it fell on Yom Kippur. “It always seems to come up in the big situations,” Green says. “But I felt it was the right thing to do even though I'm not particularly religious. A lot of people in the Jewish communities recognize me as a Jewish athlete they can relate to, and I felt it was important to set a good example.”

(In the fall of 2004 he again faced the play-or-pray conundrum on Yom Kippur: he had to decide whether to miss two crucial games in the pennant race against the San Francisco Giants: One fell on Kol Nidre night, the other the next day. After agonizing for a period, he chose to play on Kol Nidre and ended up hitting the game-winning home run. The next day, he skipped the game and went to synagogue.)

I wonder what his heritage means to him, now that he's been forced to be more Jewish than he otherwise might have been if he hadn't become famous. “That's a tough question,” he says. “I've definitely learned a lot more about it since I've been playing. I think it's just a sense of pride you have about what Jewish people have accomplished, what they've been through, all the obstacles. It seems like there's never-ending struggles for Israeli people and Jewish people. It's a very strong and relentless group.”

How would he explain why there's still so much excitement about a Jewish sports star todayâwhy it's such a big deal? “I didn't know it was,” he jokes, smiling. “I think the stereotype is that the biggest asset for Jewish people usually isn't athleticism,” he says. “So when there are successful players in sports who are Jewish, the Jewish communities across the country say, âSee, we can do that.' It's something I can understand especially as a kid: If you're Jewish, you can relate to someone who celebrates the same holidays you do, who was raised in a similar household. That's the player that you're going to say, âWow; I'm sort of like him.'”

The player who inspired Green as a boy was Koufax. “I didn't see him play, he was before my time, but he was obviously the big one. And I remember hearing that Rod Carew had converted. Whether or not that's true, I don't know, but I collected his baseball cards. I remember Steve Stone was Jewish.”

Green says that growing up, he wasn't as fixated on Greenberg's career (ironically, “Greenberg” was Green's original family name), but he was an expert on Koufax, who is now a familiar presence during spring training. “Every spring he comes out to Dodgertown,” Green says. “He still lives down there in Florida. I talk to him about life and baseball; we really don't talk much about being Jewish athletes.”

Has Koufax offered any advice about being an exemplar for Jews? “He just told me that you've got to do what you feel in your heart to do and everything else will take care of itself; you can't try to please everybody.”

Green learned that lesson as a teenager when he decided to forgo college for baseballânot his mother's plan. After a straight-A high school record, ranked third in his class, he was admitted to Stanford University. Judy Green wanted him to go. “My mom was hoping that I would go to school; I actually took courses there in the winters. But my dad was kind of focused more on the professional baseball side, so there was a kind of split.” (Green's father, formerly a gym teacher, coach, and medical supplies salesman, owns an indoor-batting facility, the Baseball Academy, near his home in Tustin, California.) “But then when I signed with the Blue Jays, the team said I could go to college in the off-season, and they paid for it in the contract. So it was kind of the best of both worlds.” He attended Stanford for two years until he was offered the mega contract.

Judy Green was quoted in

Sports Illustrated

talking about her son's new salary. “I think our society is out of whack,” she said. “When you think about what policemen, schoolteachers, firemen, and paramedics do and what they are making, it's crazy what we pay our athletes and entertainers. But I know the money won't change Shawn. I know he'll do the right thing with it.”

Her son confesses it's an added pressure. “I was raised with Jewish valuesâjust to be appreciative of what you have and know that other people are in need. Jewish people traditionally are very charitable and it's hard in some ways to be in the position I'm in because you never feel like you're doing enough, and then at the same time, you keep getting bombarded and you want to go, âWhoa.' It's a tough mix.”

The other major pull in his life these days is his daughter, Presley Taylor, born December 22, 2002. It's Green's first child with wife Lindsay Bear. “My wife's not Jewish,” he volunteers. “Now that I have a daughter, we're going to expose her to both religions. I will go to synagogue on the High Holy Days, but sometimes I find it's almost harder to go because it's kind of uncomfortable for me to get a lot of attention there. It kind of all depends on how I'm feeling. Sometimes I would rather stay home and not deal with all that.”

I wonder if having a child has intensified issues of identity for him. “Definitely,” Green says with a nod. “I think it's great because she can learn two completely different religions and ways of life, not to mention that she gets extra holidays. I'm always of the belief that you should expose your kids to different things and let them find their way.”

So he didn't feel the typical family pressure to marry a Jew? Green smiles. “It's always there a little bit,” he concedes. “But you get through that fast.”

When I ask about anti-Semitic jokes in the locker room, Green waves it off. “You hear things casually,” he concedes, “but not any more than you would hear it if you were working in a nine-to-five job.” Since he is outnumbered by non-Jews in his profession, it was a memorable moment in 1998 in Milwaukee when three Jews stood at home plate simultaneously: Green was up at bat; Jesse Levis, then of the Milwaukee Brewers, was catching; and Al Clark was the umpire. “It was right after Rosh Hashanah,” Green told the L.A. Times. “And, after greeting each other with a laughing round of âHey, Yids,' we wished each other a happy new year.”

Green's next interviewer is cooling his heels nearby, so I wrap it up by asking him about the symbolism of his success. Since athletics is still an area where there aren't the equivalent of hundreds of Jewish Nobel Prize winners, he must be aware that he's breaking ground. “Obviously the ground has been broken for me,” Green demurs. “There's always been a Jewish player that's been the most recognized in the Jewish community. Since I've been playing, there have been some other players who have been up and down, but I understand that my role is to be that guy for this generation. And someone else will come along sometime and take the torch.”

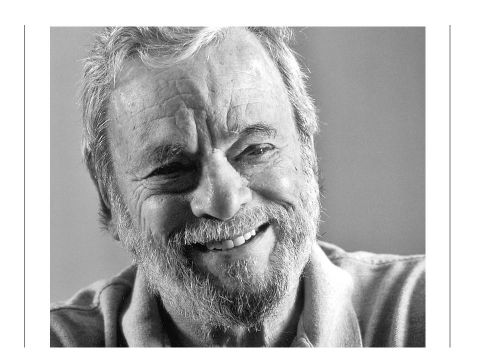

Stephen Sondheim

STEPHEN SONDHEIM PHOTOGRAPHED BY JERRY JACKSON

“I THINK JEWS ARE SMARTER than any other race.” Composer Stephen Sondheim is talking to me on the telephone. He responded to my request for a meeting with a typed note that said,

“Might it be possible to do

it over the phone instead of in person? I really hate to make appointments except

when I have to (with doctors and dentists).”

Did he just say Jews are smarter than any other race? “I'm prejudiced,” he continues. “I identify with people who get beaten up. I'm in a profession that invites it.” Meaning? “The critics.”

Sondheim, whose résumé includes

Company, A Little Night Music,

Sweeney Todd, Sunday in the Park with George

, and

Assassins

, grew up in the tony San Remo apartment building on Central Park West. “I grew up thinking the Jews were the world,” he says. “Everybody was just Jewish. I went to summer camps where everyone was named Nussbaum.”

His father was a dressmaker who “raised a lot of money for the UJA.” His mother, who is described in Sondheim's biography as emotionally abusive, “was sort of ashamed of being a Jew,” he says. “She claims she was brought up in a convent in Rhode Island.

“The first serious Jew I came into contact with was Lenny Bernstein.” Sondheim is speaking of the celebrated composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein, whose music accompanied Sondheim's lyrics for

West Side Story

in 1957. “Lenny looked at me askance when I said âYum Kipper.' I grew up not knowing anything. We celebrated Christmas by buying things at Saks. You know what I mean by a West Side Jew.”

Did he ever experience any anti-Semitism in his profession? “My Godâin the theater? In musicals? Name me three gentile composers.”

None come immediately to mind. “Cole Porter,” he helps me. “He is one of the three gentile composers. But his music is actually very Jewish. He was very influenced by the Mideastâhe was in the Foreign Legion as a young man. His music is very Semitic. Semitic scales. Listen to any Cole Porter song in a minor key; you'll hear it.”

I wonder if he's ever considered exploring Jewish themes in his work. “Not really.”

Does he have any special feeling for Israel? “My attitude toward Israel is the

New York Times

' attitude toward Israel,” he replies. “Whatever they tell me is what I believe. I became aware of Israel because Lenny cared so much about it.”

I can see my brief telephone time is almost up, so I try to clarify how Sondheim would characterize his Jewish identification. “It's very deep,” he answers immediately. “It's the fact that so many of the people I admire in the arts are Jewish. And art is as close to a religion as I have.”