Starcross (23 page)

Authors: Philip Reeve

‘Oh, Mrs Spinnaker!’ I cried – but there was no time for me to explain this fresh peril to her, for at that instant the leading icthyomorph suddenly dived in and struck its bony pate against our canopy. I saw, as it dinged against the glass, that the Moob upon its head had braced itself for the shock by extending its little arms and clasping

its small black hands together beneath the fish’s chin, so that the impact should not hurl it off. The glass was thick, and the fish swam away dazed, having done no damage, yet there were a great many others, and their heads came battering against the canopy like the blows of tiny hammers. It was not long before one pane cracked, and then another, and our ears filled with the ominous hiss of air escaping from the canopy.

A human being may breath pure aether for a while, as all those fishes and other creatures do, but not for long. An hour or two at most, I believe. Yet countless miles still separated us from our destination! If all our air escaped, we should expire long before we reached it!

And now the train that bore us on was slowing, and along the sides of the locomotives, clad in tarpaulin suits and fireproof gloves which they must have found in the guard’s van, Colonel Quivering and Mr Grindle came scrambling, each with his hat in place and a spare Moob hanging at his waist, ready to fit upon the heads of myself and Mrs Spinnaker!

But they never reached us. For the mechanism of the hand-car, which had been pumping and see-sawing away so furiously all this time, chose that instant to break. A spring

gave way somewhere beneath the floor with a dreadful crack, an axle parted, and the hand-car pitched forward and flew clean off the track, tumbling over and over through the empty aether, leaving a trail of nuts and bolts and wheels and shards of glass, while Mrs Spinnaker and I were hurled helplessly about inside like two dried peas in a rattle.

And far behind us, along that shining silver thread which was the Asteroid Belt and Minor Planets Railway, that train with its cargo of ungodly hats went thundering on its way towards Modesty, Decorum and the wider Empire!

Horrid and eerie as that empty ship had seemed before, it seemed ten times eerier and more horrid once I had read those dreadful words in Captain Melville’s log.

The Moobs! The Moobs are coming!

‘Whatever is a Moob?’ I asked, trembling a little, so that the dry old pages of the logbook in my hands rustled like

dead leaves, adding even more to the general atmosphere of Gothick dread.

‘I do not know,’ said Jack. ‘I never heard of such a thing …’

‘I have,’ said Delphine, reaching up in a hesitant and confused manner to touch her hair. ‘I had a dream, I think, about a Moob, on our first night at Starcross … Or was it a hat? Oh, the picture of it will not stay in my head!’

Jack, meanwhile, had been stirring the sad heap of Captain Melville’s clothes with the toe of his boot, so that a small quantity of cobweb-coloured powder tipped out upon the deck.

‘Whatever they were,’ he said, ‘it seems they’ve consumed your poor grandfather and his men, and eaten them up inside their clothes, bones and all. And there’s a chance they might be lingering still in these parts. So if you’ve some plan for flying this ship out of here, without an alchemist to start her engines up nor any place to go, you’d best begin. For I don’t wish to be lingering here when these Moobs return.’

Delphine nodded. She was a woman of action, as I suppose one must be if one is to make a living as a mistress of intrigue. She went at once and shouted to her goblins to

leave off their wool-gathering and set a guard upon the ship. She snatched the logbook from my hands and riffled inquisitively through its yellowed leaves. Then she went to the bookcase above Captain Melville’s bunk and took down first one, and then another book. ‘

Spatial Geography for the Aethernaut

,’ I heard her mutter, glancing at the titles. ‘

The Poems of Dryden … On Jove and Its Many Moones

… It is not here!’

‘Pray what are you searching for, Miss Beauregard?’ I asked politely.

‘Alchemy!’ returned the young lady. ‘My grandfather had vowed to publish the secrets of his art that all might learn it. I had imagined that I might find his notes here, and use them to teach myself how to pilot this vessel. But I see no notebooks here, only poems and atlases … Oh, did all his knowledge die with him?’

‘A pretty slender hope, even if it were there,’ Jack opined. ‘Gentlemen study for years and years to learn the arts of

Alchemy; I doubt you could pick it up from a book in the short time we have.’

‘Indeed,’ said Delphine, looking cross, as Delphine always did when someone ventured to contradict her. ‘But my grandfather held that that was quite unnecessary. The Royal College erects all manner of barriers about the secret of the chemical wedding, and makes its students sit through years of dreary examinations, and learn reams of Latin words and alchemical signs and symbols, but the truth is that the chemical wedding may be performed by anyone who has a talent for it. It is no harder, and no easier, than singing.’

‘Good Heavens!’ I protested. ‘What a horrid, democratic notion! Why, if that were true, then

anyone

would be able to do Alchemy – foreigners of all sorts might set up as alchemists!’

‘Indeed, Miss Mumby,’ replied Delphine, turning to me with a triumphant look, as if I had proved her point for her. ‘Did you yourself not travel through the heavens by means of Alchemy performed by the creature Ssilissa, who was not even a human being, but some unknown breed of lizard?’ And then her expression changed. Her eyes remained fixed upon me, but they took on a cunning, calculating look,

which made me grow quite uneasy.

‘And did not your own mother, Miss Mumby, steer a whole house across the Heavens, despite the fact that she has no accreditation from the Royal College of Alchemists, or any other learned body? Oh yes, my masters in Paris were most interested by that news. We are not entirely sure what Mrs Mumby

is

, but she clearly has a talent for Alchemy. And is it not possible that you, as her daughter, have inherited that talent?’

‘Most certainly not!’ I cried. ‘Young ladies do not perform Alchemy!’

21

But Delphine was not to be put off. She opened a door in the panelled wall and thrust me down a tight spiral of stairs behind it. She had no doubt studied plans and models of the

Liberty

, and so knew that this stygian stairway led into the ship’s wedding chamber, but I had no notion of what lay

below me, and cried out most piteously to Jack to save me.

‘Unhand her!’ I heard him say gallantly.

‘Stow it, Havock,’ replied Delphine, displaying that shocking want of feminine delicacy which was so typical of her. ‘I still have my revolver here, and if you try anything heroical I’ll smash your other leg.’

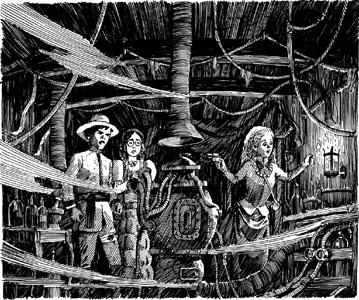

Still, Jack followed us down, and I was glad of him, for at the stairs’ foot I found myself in a most curious room, filled with pipes and tubes. Long lines of bottles gleamed dully in racks around the walls. In the midst of it was an alchemical oven or

alembic

, looking for all the world like a large pot-bellied stove.

Keeping her pistol trained on us, Delphine prowled about lighting the candles which stood in brackets upon the walls. Their gathering light raised dim reflections through the cauls of dust on all those bottles, and showed us the colours of the substances within: red Mercury, green Antimony, silver-white Newtonium and dozens more whose names I did not know.

Then, lighting a taper from the last of the candles, Delphine stooped down and kindled a fire beneath the alembic (it was an old-fashioned sort, of course, not one of the modern gas models). She bellowed for her goblins, and

told them to get stoking. Soon a veritable chain of them were passing fuel up from some store beneath the deck and feeding it into the under-parts of the alembic, which began to glow deepest cherry red and give off a dry heat which might have made me perspire, were I not so well brought-up.

‘Now,’ said Delphine (perspiring freely, of course, and pushing a curl of dampened hair out of her eyes), ‘to work,

Miss Mumby. Which elements must we combine to bring this old ship to life?’

‘I do not know!’ I cried, almost in tears, for I could not imagine how she expected me to do this incomprehensible thing.

‘Then

think

, if you please,’ she said, ‘before the Moobs come and turn us all to heaps of clothes, and you to a mere empty bathing suit!’

I stumbled to the rack of bottles and took down one, and then another, trying to read the crabbed writing and mysterious alchemical signs upon their labels. I could not; the words made no sense to me, and my tears made them hard to see. I snatched up a blackened rag which hung upon a peg beside the alembic and dried my eyes, then used it to tie back my hair, which had come quite undone with all that running about.

‘Quickly, Miss Mumby!’ my tormentor insisted, and when I looked at her, meaning to tell her that she was quite mistaken and that I had no talent, none at all, for Alchemy, she raised her gun and, pressing it against poor Jack’s temple, repeated, ‘Make my ship fly! You are your mother’s daughter, aren’t you? You

must

have the skill!’

I looked down again in desperation at the two bottles in

my hands. I did not know if it was the heat of the alembic, or some other thing, but suddenly it seemed to me that the chemicals within were brighter than before: one a vivid, acid green, the other a pleasing russet. It occurred to me that if I mixed a very little of the first with a generous portion of the second, then the green would be rendered less offensive, and the russet more pleasant still.