Starcross (22 page)

Authors: Philip Reeve

I doubled back to pull the lever which changed the points, so that the hand-car would be able to leave its siding. I had just succeeded in shifting it when sounds from behind made me look round, and then seek concealment in a handy pool of shadow beneath the water-tower.

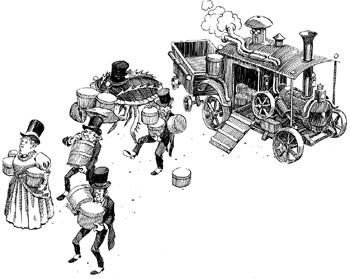

On the road from the hotel lights were showing, and in another moment a mechanised wagon came clattering and steaming into the station. My poor Moob-hatted friends piled out, intent on some fresh errand for their masters. I cursed my ill luck, for if they had arrived five minutes later I should have been safe on my way, but as it was I had no choice but to crouch there and watch as they began unloading stacks of round white objects from the wagon and carrying them in teetering piles to the waiting train.

I could not understand at first what those white things were. Giant pills? Wheels of cheese? No! A chill of pure terror run through me. They were hatboxes! And every single one, no doubt, held a Moob, waiting to spring upon the head of some unsuspecting person when the train reached Modesty and Decorum, and bend them to the Moobish will!

If I had not been so alarmed, it

might have been quite comical to spy upon my friends as they stumbled to and fro with those heaps of boxes. Hypnosis seemed to have made them clumsy, and they were forever dropping boxes, which drew indignant cries of ‘Moob!’ from those inside.

Nipper, even clumsier than the rest, at last tripped over his own feet and measured his length upon the station platform, and the hat rolled off his head and dropped with a cry of annoyance on to the rails beneath the train.

20

At once the dull light of mesmerism vanished from his eyes; they rose up on their stalks and peered about in great fear and confusion. Then, as understanding dawned, he sprang up and started to run, shouting out, ‘Help! Help! The Moobs! The Moobs are upon us!’

It was horrible to see the cold way in which the poor crab’s friends and fellow guests pursued him, and, producing a Moob from one of the boxes, forced it down upon his shell and made him meek and obedient once again. More horrible still, from my point of view, was the fact that this pursuit brought them close to where I was hiding. I

tried not to breathe or even move as the Moob-slaves turned to resume their task. But I must have made some small noise – or else Moobs can detect the thoughts of their prey – for the Moob that sat upon the head of Mrs Spinnaker, who was the last to go, suddenly swivelled around like one of the gun turrets on those new ironclad aether-dreadnoughts, and I knew that it had sensed me.

Mrs Spinnaker turned and walked towards the water-tower, closer and closer to the shadows where I was crouched. I felt about upon the ground for some weapon I might use to defend myself, but found none. Then I saw the dangling chain which operated the tower. As Mrs Spinnaker saw me, and turned to call out to the others, I leapt up and pulled it. The tower’s hose swung out like the trunk of a helpful iron elephant, and a white

cataract of chilly water engulfed Mrs Spinnaker and myself, quite blinding us both for a moment and knocking us to the ground. As I had hoped, it startled Mrs Spinnaker’s Moobish hat, which fell from her head, losing its hat-shape, coughing and spluttering and choking and waving its tiny hands about.

‘Oh lawks!’ exclaimed Mrs Spinnaker. ‘

Now

where am I?’

‘Run, Mrs Spinnaker!’ I shouted, for already the Moobs’ other slaves were hastening to where we sat. ‘That hand-car is our only hope!’

A lady as large as Mrs S. does not rise easily, especially when her clothes are sodden with water, and Colonel Quivering and Nipper were almost upon us by the time I had her upright. But she felled Nipper with a firm punch upon the carapace, a technique she had no doubt picked up in the East End pubs where she had started her career, and, taking my hand, let me lead her across the confusion of starlit rails and sleepers to the waiting car.

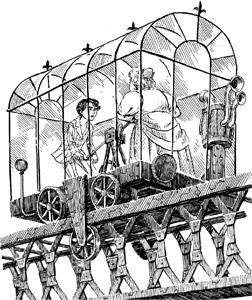

It was unlocked, thank Heaven! We leapt aboard – I seized a handle and Mrs Spinnaker seized the other – and together we began to heave for dear life. With painful sloth at first, but swiftly gathering speed, the hand-car started to move. It wiggled its way over the points I had set for it, and

started up the long slope of the bridge, which was not as hard a climb as I had feared, for Starcross’s gravity soon released its grip upon us, and we were in space, where there is neither up nor down and precious little friction, so that an object once set in motion may carry almost for ever. We continued working the car’s handle regardless, until it was singing along the rails at a speed of several hundred miles per hour.

Then, breathless, we paused in our labours and, avoiding the handles, which continued to pump up and down on their own, looked out through the back of the car’s glass canopy. Starcross was a speck astern, dwindling into the asteroid-freckled sky.

‘My poor ’Erbert!’ sighed Mrs Spinnaker, wringing out the wet hems of her

skirts. ‘He never did ’ave much brain, and now what ’e ’ad’s been stolen.’

‘Don’t worry, Mrs Spinnaker,’ I said bravely – for it is the duty of a British boy to keep up the spirits of those about him at times like that – ‘we shall return, and save him. We’ll get to Modesty and Decorum, and let the authorities there know what’s what.’

‘We’ll have to hurry, then,’ said Mrs S. ‘Look!’

She pointed out through the glass. Far behind us, where the bright rails narrowed towards distant Starcross like a diagram of perspective in a drawing class, I saw a white cauliflower-shape bloom against the dark.

‘Steam!’ I cried.

‘The train!’ said Mrs Spinnaker. ‘They’re coming after us!’

‘We’re done for!’ I said despondently. ‘Now I shall never save Mother, nor find out what has become of poor Myrtle …’

Then it was time for Mrs Spinnaker to raise

my

spirits, which she did by directing me to take my place again at the handle. ‘How fast can we make this contraption go?’ she wondered. ‘Pretty fast, I reckon. Faster than that train? Well, maybe. And let’s ’ave a song to cheer us on our way; those Moobs won’t be singing, and perhaps that’s how we’ll best

’em, eh, Art?’

And so we sang. We sang ‘My Flat Cat’ and ‘Nobby Knocker’s Noggin’. We sang ‘Tom O’Bedlam’ and ‘Ganymede Fair’. We sang and pumped, and pumped and sang, and our wet clothes steamed, filling the cabin with a smell of damp serge, while the asteroids and spatial reefs turned to the merest blur beyond our windows.

What a race that was! The hand-car had no speedometer, so I cannot be sure, but I am willing to wager that it was moving faster than any hand-car has in the whole history of the Solar Realms, or ever shall!

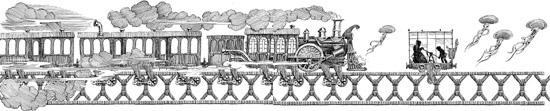

And yet, for all our songs and striving, the Moobs’ train moved faster. Mrs Spinnaker had her back to it, but when I looked past her through the hand-car’s canopy I could see it drawing ever nearer. At first it was a mere cloud of steam,

then steam and lights. For a while, on a long bend, it must have slowed, for it fell back and I felt sure that we were winning. But then it began to gain on us steadily, until I could see the brass handle gleaming on the front of its boiler and the grid-like catcher it carried to shove luckless aetheric wildlife from its path.

‘Mrs Spinnaker?’ I ventured.

‘What’s that, dearie?’ The good woman’s face was quite glowing with the effort of her exertions. ‘Sing up!’ she advised.

I joined her in another merry chorus of ‘Dearest Margaret, You Are Danish and Your Dog’s Not Very Well’ (that old music-hall favourite) but it was no use; the train looming behind her posed too much of a distraction. And as she commenced the next verse, the locomotive surged up

in a pother of steam and cinders and gave our hand-car a nudge with the tip of its aetheric cow-catcher, such that we were thrown about inside our glass canopy, and even Mrs Spinnaker grew too distracted to sing any more.

‘But this ain’t so bad!’ she said brightly, as the train barged us along. ‘They are just pushing us ahead of them. I don’t see how they can reach us, an’ make us put on those ’orrid tiles again. They’d burn themselves on that great steamy boiler if they tried it!’

I did not reply. For one thing, I did not believe the Moobs would be much troubled if our friends burned themselves in order to recapture us. For another, I had just noticed something strange outside the glass.

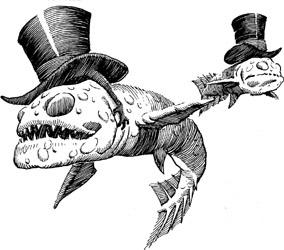

It was hard to see at first, what with all the steam and sparks gushing about, and the reflections of me and Mrs Spinnaker and the frantically see-sawing mechanism of the car filling every pane. But after a few seconds the gas lamp in the hand-car roof failed, which cut out the reflections somewhat, and by the ruddy glow of the locomotive’s fires and the lightning-blue glare of the sparks which leapt up betimes from its hurrying wheels I saw the new phenomena quite clearly. An aetheric icthyomorph was keeping pace with our hand-car, very close. And out in the dark behind it

swam another and another – a whole school of them, tails flicking frantically to and fro as they drove themselves through the aether at the same speed as the Moobs’ locomotive. They were common red whizzers (

Pseudomullus vulgaris

) such as I had oft seen swim in and out among the chimney stacks at Larklight – but I had never seen them whiz quite so fast as this. And when I looked closer I soon saw the reason why they were so interested in us and our hand-car … For each of those fishes wore a sinister grin, and upon the head of every one there sat a

black top hat

!