Spitfire Girl (29 page)

Authors: Jackie Moggridge

Like horses headed for the stables the Spitfires eagerly spanned the last few miles. Soon, the gigantic Shwe Dagon pagoda, a fabulous Buddhist shrine plated with gold, rose massively three hundred feet from the squalor of Rangoon and glinted like a rising sun on the horizon. In its jewel-encrusted peak rested Buddha’s tooth and a lock of hair, ornaments of faith that drew pilgrims from the scattered corners of the world and sign-posted

finis

to our flight.

We flashed across the aerodrome in tight V formation, peeled off and beat-up the hangars, before side-slipping in to land. I switched off with a curious mixture of elation and sadness and slumped in the cockpit as the instruments dropped slowly to zero.

‘Hi,’ shouted a Burmese supply officer laconically, as though we had just completed a meek little flight from an airfield nearby.

‘Hi,’ I answered, determined to be equally unceremonious. Little earth-bound mortal. How could he know that parched deserts, proud mountains and the conquest of fear sat with me in the cockpit, binding me closer to this inanimate thing of metal than to him, denizen of a smaller world.

‘Any news of Gordon Levett?’ I asked as I handed him the delivery documents.

He frowned.

‘The other Spitfire,’ I prompted.

‘Oh. Yes. He left Bandar Abbas yesterday.’

‘Is the pilot all right?’

‘U-huh. We expect him in a few days. Where are the spare radio crystals?’ he added nonchalantly.

I pulled off my helmet, pushed my hair back and pointed to the wing panels. He shrugged and disappeared under the wing.

So, on a note of absurd anti-climax, ended the fourth ferry flight.

How to end this book when there is no ending? I am too

young to sum up, too old to end with a hint of a new beginning. There seem very few ends that need gathering. Gordon Levett arrived safely at Rangoon and joined us at Tel Aviv in time for the remaining two ferry flights.

At the end of the Spitfire contract I hitch-hiked back to London on an Israeli Air Force freighter. As we crossed the Alps at night I sat at the controls. The rest of the crew were dozing when the clouds broke like a curtain to reveal the splendid sweep of the Bernese Alps. The moon, luminous as a pearl in the oyster of night, caressed the snow-clad peaks with shafts of quicksilver that lent depth by giving shadows to the valleys between. Peak upon peak reached for the sky like silvered pagodas. Swiftly the broken clouds sped past the moon switching its spotlight from one superb peak to another. New peaks rose to be admired, posed for an instant, then slipped into shadow. The slopes in the reflected light from the glaciers looked like the tinselled skirts of ballerinas. The frozen lakes like a hundred moons. And, I thought, as the peaks spotlighted the horizon for a brief moment before being snuffed out by distance, people ask me why I do not give up flying.

Here then, a copy of a recent advertisement, is the end:

‘Woman pilot, 35, Commercial Licence and Instrument Rating, 3500 hours. Recent experience Far-East ferrying. Seeks flying post Home or Overseas. Box 467.’

We hope you enjoyed this book.

For more information, click one of the links below:

~

An invitation from the publisher

In 1979, Nick Grace, design engineer and qualified pilot, acquired Spitfire ML407 from a museum. Over the next five years he painstakingly restored the aircraft back to flying condition, and in 1985 Nick finally had his Spitfire airborne again. When Nick died tragically in a car accident in 1988, his wife Carolyn, a relatively inexperienced pilot, took on learning to fly the Spitfire in order to keep a Grace in the cockpit.

The historian tracing the history of their Spitfire told Nick and Carolyn that it was first flown by ATA Pilot Jackie Moggridge on 29 April 1944

.

As a pilot myself, I have found all the ladies who flew in the ATA to be a huge inspiration. What they achieved in a male-orientated environment, during a time when women weren’t expected to drive a car, let alone pilot an aircraft, is incredible. When the historian Hugh Smallwood told me that the famous woman pilot, Jackie Moggridge, had been the first to fly our Spitfire I was deeply moved.

I first met Jackie when we were making

The Perfect Lady

, a documentary about our Spitfire. She came to Land’s End Airfield where we were filming and I was so in awe of her I could hardly speak, but she immediately put me at ease.

Looking through Jackie’s logbook entry from the 29 April 1944, it’s possible to re-visit the aircraft’s first flight. ML407 was one of two Spitfires Jackie delivered that day – and it was supposed to be her day off! On the 27th and 28th she had delivered a Beaufighter (Bomber), Hawker Typhoon (Fighter), another Spitfire as well as flying the transport aircraft Oxford and Anson. Quite a schedule! Jackie delivered ML407 to 485 New Zealand Squadron where it became the ‘mount’ of Flying Officer Johnnie Houlton DFC who was accredited, whilst flying ML407, with the first enemy aircraft shot down over the Normandy beachhead on the 6 June, D-Day.

I decided to recreate this first flight: Jackie and I would re-deliver the Spitfire to its original pilot fifty years after its first flight. I had gathered together twenty members of the original 485 Squadron ground crew to be with Johnnie to receive their Spitfire again. On 29 April 1994 there Jackie was, standing beside ‘her’ aircraft that embodied so much history, looking wonderful in her ATA uniform which still fitted her perfectly.

Jackie was, by her own admission, not a good passenger! She had told me she didn’t want to pilot the Spitfire herself. As we took off from North Weald for our ‘delivery’ I decided something must be done. Once we were airborne, I told Jackie that I had dropped my map so she would have to take control of the aircraft. As a Spitfire has no floor, Jackie knew this was a potentially serious situation and immediately said, ‘I have control’. Of course I hadn’t really dropped anything, but I knew this was the best way to make her fly her Spitfire again. As we approached Duxford, another Spitfire pilot suggested we fly together for a flypast down the runway. Jackie flew ML407 beautifully low down the runway in formation with the other Spitfire.

After this flight, Jackie and I formed a bond I treasure to this day. In what is still a male-dominated profession, she would be sure always to look her best, having her lovely hair flow free when she removed her flying helmet to accentuate her femininity. She would ensure her make-up was perfect and carried a pair of high-heeled shoes to put on when she alighted from her aircraft. I remember her telling me at the Duxford Air Show to change into my slimmer-fit flying suit in order to show my figure off better. In an environment where everything is practical and serves a purpose, Jackie injected some much-needed glamour.

But Jackie was also an expert pilot, capable of flying a wide variety of aircraft types. She would have ferried these war machines unarmed, usually in dangerous circumstances. By the end of the war Jackie had delivered more aircraft than any other member of the ATA, male or female, an incredible achievement. All this she did whilst managing the complications of family life – what a lady!

It was with great sadness but immense honour that I scattered Jackie’s ashes from her Spitfire on 1 August 2004: an appropriate ending to an inspirational life.

Carolyn Grace, May 2014

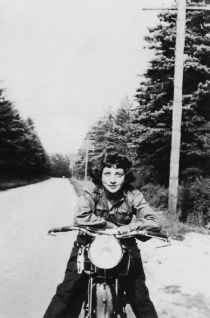

Dolores Teresa Sorour, born 1 March, 1920. She became Jackie in her teens, refusing to answer to any other name.

Jackie’s beloved grandmother Helen Sarkis. ‘Old-fashioned and strong willed’, but Jackie adored her.

Jackie and her mother Veronica in South Africa c.1937.

Preparing for her parachute jump, in front of the de Havilland Moth, at Swartkop Aerodrome. They had no suits small enough to fit a 17-year-old girl – only men jumped out of planes in those days – so Jackie’s tiny frame was completely

‘I saw polo players approaching on horseback like an army of Pegasus.’ Jackie, the first South African woman to perform a solo parachute jump, is carried back to the aerodrome with a broken ankle.