Sons (36 page)

Authors: Evan Hunter

“A

goddamn

Red, in fact,” I said.

goddamn

Red, in fact,” I said.

“Please, there are ladies present,” Rosie said in mock affront, and wiggled her black eyebrows at Nancy, who again laughed.

“We were talking about the strike,” Allen said.

“Grrrrrrr,” Rosie said. “He reminds me of a grizzly when he’s this way. Look at him. Grrrrrrrr,” she said again, and tousled his short blond hair, and said, “Doesn’t he look just like a bear, Bert?”

(He lay silent and motionless with one hand still clasped over the base of his skull, just below the protective line of his helmet. There was no blood on him, no scorched and smoking fabric to indicate he’d been hit.)

“Bert?”

(And then I saw the steel sliver that had pierced the top of his helmet, sticking out of the metal and the skull beneath it like a rusty railroad spike. “Timothy?” I said again, but I knew that he was dead.)

“Bert’s out gathering wood violets,” Nancy said.

“No, Bert is sulking,” Rosie said.

I did not answer. I was wondering all at once about having made the world safe for democracy. As Allen sat opposite me and glowered in suspicion, I found myself thinking something seditious, thinking something traitorous, thinking (God forgive me) that perhaps Timothy Bear had been duped into giving his life for a slogan that was meaningless, that maybe there was no such thing as freedom, not in America, not anywhere in the world, that perhaps the boundaries of freedom would always be as rigidly defined as the boundaries of the Twenty-ninth Street Beach had been this past July, where trespassing had led to stoning and to death. I found myself overwhelmed by a wave of patriotic feeling such as I had never experienced before (not even when the German guns were sounding all around me), and I suddenly realized that America was only now, only right this minute beginning to test the strength of a political idea that was more revolutionary than anything that had ever come out of Russia, testing it in a hundred subtle and unsubtle ways, not the least of which was the unexpected appearance of a lone Negro on a forbidden beach. And I wondered, exultantly, hopefully, fearfully, what would happen when America decided to find out

exactly

what freedom meant,

exactly

to what limits freedom extended.

exactly

what freedom meant,

exactly

to what limits freedom extended.

“All right, I know you’re not a goddamn Red,” Allen mumbled at last.

“Grrrrrrrr,” Rosie said.

NovemberIt was two days after Thanksgiving, two years and a bit more after President Kennedy had been shot and killed. We stood in an early morning drizzle along the stone wall that was the eastern boundary of Bryant Park in this city where I’d been born. There were fifty of us, more or less, waiting for the bus that would take us to the nation’s capital, where we could make our protest known against the war in Vietnam.

Similar groups were waiting at thirty other pickup points throughout the city, and two special trains hopefully packed with demonstrators were scheduled to leave from Pennsylvania Station later that morning. The march on Washington had been conceived and co-ordinated by the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, and the group’s expectation was that a crowd in excess of 50,000 concerned Americans from all over the country would surround the White House demanding peace in Southeast Asia. Sixty-five hundred demonstrators were supposed to be leaving from New York City, and SANE had calculated that 141 buses would be needed to take them south. By Friday evening, they had received definite commitments for 84 buses, and were hoping to charter an additional 31 coaches from Greyhound, and another 50 from a Connecticut company, more than enough to carry even a larger crowd than anticipated. But now, on Saturday morning, as a gray and sunless dawn broke over the New York Public Library, there was trouble already and we were being told by the marshal of the Bryant Park contingent that a rally had been scheduled for nine that morning for those of us who might never make it to Washington.

The problem, it seemed, had originated with the bus drivers’ unions. Jackie Gleason had elevated the bus driver to the plane of a national folk hero with his weekly portrayal of the boisterous Ralph Kramden, and thus intellectually inspired, thus cognizant of their role in history and eager to protect and preserve the republic against subversives, anarchists, beatniks, and the like, the bus drivers of America had refused to man the buses chartered for the trip, and only forty-eight of the committed vehicles had arrived at the scheduled pickup points. It appeared to the SANE officials that this was surely an illegal restraint of interstate travel, but in the meantime we demonstrators stood chilled and despondent in a city silenced by the long weekend holiday, the leafless trees around us sodden and stark against a monochromatic sky.

Dana had once written a skit about some North American Indians called the Ute, their unique characteristic being that everyone in the tribe was under the age of twenty-live. (

Ute,

don’t you get it? she said,

Ute!

and I advised her that her sense of humor was far too excellent to be wasted on a cheap pun. Later that same day, when I told her we needed a new light bulb for the fixture over the sink, she convulsed me by replying, “Sure. What watt, Wat?”) Anyway, it dismayed me to discover that not too many Utes were now in evidence in Bryant Park. The drizzle may have had something to do with that, or perhaps the fact that so many of the sponsoring organizations had such long names; the Ute of America, Dana had pointed out in her witless skit, preferred ideas to be short and to the point, preferably capable of being expressed in a single word, or better yet, a symbol. It was now close to seven a. m., I guessed, and the crowd had grown to perhaps sixty or seventy people, but I saw only a dozen kids our age, half of whom were obvious beatniks with long hair, dungaree jackets, and boots. The absence of more Utes in the assemblage may have accounted for our very orderly controlled manner; we looked less like demonstrators than we did a queue of polite Englishmen waiting outside a chemist's shop. The steady drizzle did nothing to elevate our spirits, nor did the nagging knowledge that perhaps our early morning appearance here was all in vain, there would be no goddamn transportation to Washington. Even the arrival of a bright red Transit Charter Service bus elicited nothing more than a faint sigh of relief from the crowd. Had there been more Utes present, the sigh might have become a cheer. In this crowd of octogenarians, however, it sounded more like a groan from a terminal cancer patient. Well, octogenarians wasn’t quite fair. There was, to be truthful, only a sprinkling of very old people moving quietly toward the waiting bus. The remainder belonged to that other great Indian tribe (also made famous in Dana’s skit) the Cholesterol, easily recognized by balding pates and spreading seats, strings of wampum about their necks, golden tongues (never forked) spouting pledges, promises, admonitions, and advice to their less fortunate brothers, the Ute. Maybe that wasn’t fair, either. What the hell, we were

all

standing there in a penetrating November drizzle, all with our separate doubts, all hearing the marshal advising us that we would load from the front of the line (a senseless piece of information since I had never waited on any line that loaded from the

rear)

and then asking, “Where are those two girls?” to which a long-haired beatnik replied,

“Boy,

if you please!” and the marshal said, “You can’t prove it by me. Am I that square?” and a member of the mighty Cholesterol shouted, “No, you’re not!” a good homogeneous mixture of marchers we were taking to Washington that day.

Ute,

don’t you get it? she said,

Ute!

and I advised her that her sense of humor was far too excellent to be wasted on a cheap pun. Later that same day, when I told her we needed a new light bulb for the fixture over the sink, she convulsed me by replying, “Sure. What watt, Wat?”) Anyway, it dismayed me to discover that not too many Utes were now in evidence in Bryant Park. The drizzle may have had something to do with that, or perhaps the fact that so many of the sponsoring organizations had such long names; the Ute of America, Dana had pointed out in her witless skit, preferred ideas to be short and to the point, preferably capable of being expressed in a single word, or better yet, a symbol. It was now close to seven a. m., I guessed, and the crowd had grown to perhaps sixty or seventy people, but I saw only a dozen kids our age, half of whom were obvious beatniks with long hair, dungaree jackets, and boots. The absence of more Utes in the assemblage may have accounted for our very orderly controlled manner; we looked less like demonstrators than we did a queue of polite Englishmen waiting outside a chemist's shop. The steady drizzle did nothing to elevate our spirits, nor did the nagging knowledge that perhaps our early morning appearance here was all in vain, there would be no goddamn transportation to Washington. Even the arrival of a bright red Transit Charter Service bus elicited nothing more than a faint sigh of relief from the crowd. Had there been more Utes present, the sigh might have become a cheer. In this crowd of octogenarians, however, it sounded more like a groan from a terminal cancer patient. Well, octogenarians wasn’t quite fair. There was, to be truthful, only a sprinkling of very old people moving quietly toward the waiting bus. The remainder belonged to that other great Indian tribe (also made famous in Dana’s skit) the Cholesterol, easily recognized by balding pates and spreading seats, strings of wampum about their necks, golden tongues (never forked) spouting pledges, promises, admonitions, and advice to their less fortunate brothers, the Ute. Maybe that wasn’t fair, either. What the hell, we were

all

standing there in a penetrating November drizzle, all with our separate doubts, all hearing the marshal advising us that we would load from the front of the line (a senseless piece of information since I had never waited on any line that loaded from the

rear)

and then asking, “Where are those two girls?” to which a long-haired beatnik replied,

“Boy,

if you please!” and the marshal said, “You can’t prove it by me. Am I that square?” and a member of the mighty Cholesterol shouted, “No, you’re not!” a good homogeneous mixture of marchers we were taking to Washington that day.

There was not enough room on the single bus for all the people moving in an orderly line toward the Sixth Avenue curb. But a row of private cars with vacant seats in them was pulling in behind the bus now, and people began dropping out of the line in twos and threes, always in order, to enter the cars and be driven off into the gray wet dawn. Dana and I waited our turn. By seven-thirty we were aboard the bus, and in another ten minutes the doors closed and we pulled away from the curb and headed for the Lincoln Tunnel.

I felt apprehensive, but I could not explain why.

It had rained in Washington, too, and the streets were still wet when we assembled outside the White House at eleven o’clock that morning. The sun was beginning to break through. Looking across the Ellipse, I could see the obelisk of the Washington Monument wreathed in clouds that began tearing away in patches to reveal a fresh blue sky beyond. It was going to be a beautiful day after all, clear and sunny, the temperature already beginning to rise, and with it the spirits of the protesters. The organizers of the march were passing out signs on long wooden sticks, each bearing a carefully selected slogan. My sign read, vertically:

WARerodes

the

Great

Society

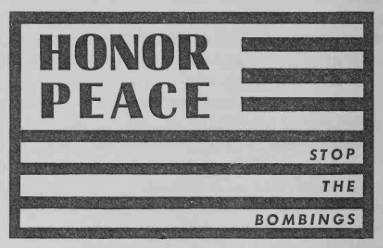

Dana carried a sign in the shape of an American flag, the field of stars in the left-hand corner replaced by a slogan, the bottom three white stripes lettered with a second slogan, so that the message read:

There were additional slogans as well, all of them muted in tone as befitted the dignified approach of the sponsoring groups, all of them professionally printed by the hundreds, except for the dozen or so hand-lettered posters carried by some of the more militant forces who seemed to be shaping up into cadres of their own, signs that blared in blood-dripping red U.S. IS THE AGGRESSOR or AMERICA, GET OUT NOW! I noticed, too, as I lifted my sign and rested the wooden handle on my shoulder, that some of the hard-core cadres were carrying furled Vietcong flags, and my sense of apprehension grew, though I could not imagine trouble in this orderly crowd, the soft-spoken monitors explaining what we would do, the clouds above all but gone now, a robin’s egg blue sky spreading benignly over the glistening wet white clean buildings of the capital.

The appearance of the first swastika was shocking.

We were marching along three sides of the White House, STEPS TO PEACE, STOP THE BOMBINGS, flanked by the wrought iron fence surrounding the lawn and the wooden police barricades set up to bisect the wide sidewalk, RESPECT 1954 GENEVA ACCORDS, the police watching with a faint air of familiar boredom, apparently without any sense of impending trouble, “NO MORE WAR, WAR NEVER AGAIN” — POPE PAUL, no one chanting or singing, even the militants looking oddly suppressed save for the anticipatory fire in their eyes and the color of the now unfurled Vietcong flags, when suddenly the storm troopers appeared in Army fatigues and combat boots, swastika armbands on their shirtsleeves, George Lincoln Rockwell’s American Nazi elite, one of whom held in his right hand a fire-engine red can with the label GAS on it, and in his left hand a sign reading FREE GASOLINE AND MATCHES FOR PEACE CREEPS.

The reference, of course, was to the two immolations within as many weeks this November, the first having taken place outside the river entrance to the Pentagon, not three miles from where we now marched, when a thirty-one-year-old Quaker named Norman Morrison drenched his clothes with gasoline and, holding his eighteen-month-old daughter in his arms, set fire to himself in protest against the Vietnam War. An Army major managed to grab the child away from him in time, but Morrison could not be saved, and he was declared dead on arrival at the Fort Meyer Army Dispensary. A week later, a twenty-two-year-old Roman Catholic named Roger LaPorte set himself ablaze outside the United Nations building in New York City, and died some thirty-three hours later, still in coma. The immensity of those gestures, ill-advised or otherwise, coupled with the memory of Jews being incinerated by Nazis in the all-too-recent past

(Judgment at Nuremburg

had taken two Academy Awards not five years ago!) transformed this

American

Nazi’s at best insensitive offer into an act at once barbaric and intolerable. It was no surprise that someone rushed him, yanked the armband from his shirtsleeve, and began tearing his poster to shreds. (The surprise came later; his attacker turned out to be an ex-Marine who, like the Nazi, was

opposed

to the march.)

(Judgment at Nuremburg

had taken two Academy Awards not five years ago!) transformed this

American

Nazi’s at best insensitive offer into an act at once barbaric and intolerable. It was no surprise that someone rushed him, yanked the armband from his shirtsleeve, and began tearing his poster to shreds. (The surprise came later; his attacker turned out to be an ex-Marine who, like the Nazi, was

opposed

to the march.)

I expected trouble to erupt full-blown then and there.

I saw another Nazi rushing forward with a poster that read IN WAR, THERE IS NO SUBSTITUTE FOR VICTORY, wielding the sign like a baseball bat, Vietcong flags on poles being lowered like spears now, a minor war paradoxically about to begin on the fringes of a protest

against

war. There was a lunatic aspect to the scene, the row of orderly marchers with their beautifully rendered posters, a middle-aged phalanx that circled the White House in the company of a sparse number of Utes, while Vietcong flags confronted Nazi swastikas, schizophrenia in the sunshine, the Washington police seemingly as dazed as the photographers, but only for a moment. Swiftly, efficiently, they moved in to break up the scuffle. Flash bulbs popped too late. My head was turned away, there was no danger that a recognizable photograph of me would appear on the front page of the New York

Times.

(Was this in my mind even then, the persistent rumor that draft boards were deliberately calling up peace demonstrators in reprisal, was this what caused my apprehension?)

against

war. There was a lunatic aspect to the scene, the row of orderly marchers with their beautifully rendered posters, a middle-aged phalanx that circled the White House in the company of a sparse number of Utes, while Vietcong flags confronted Nazi swastikas, schizophrenia in the sunshine, the Washington police seemingly as dazed as the photographers, but only for a moment. Swiftly, efficiently, they moved in to break up the scuffle. Flash bulbs popped too late. My head was turned away, there was no danger that a recognizable photograph of me would appear on the front page of the New York

Times.

(Was this in my mind even then, the persistent rumor that draft boards were deliberately calling up peace demonstrators in reprisal, was this what caused my apprehension?)

Other books

Search for Safety: Killing the Dead Book Two by Richard Murray

Romance: Duplicity (Duplicity New Adult Romance Book 1) by Knight, K.T.

The Bridesmaid's Best Man by Susanna Carr

Soulstice (The Souled Series) by Murdock, Diana

Competing With the Star (Star #2) by Krysten Lindsay Hager

Mary Stuart by Stefan Zweig

Montana Legend (Harlequin Historical, No. 624) by Jillian Hart

TheRedKing by Kate Hill

Infection Z 3 by Ryan Casey