Somebody to Love? (7 page)

Richard Anderson, another actor friend of Cece's, was a bit older (twenty-nine?) than we were, so I considered him ancient. Cece liked them well seasoned—she later married director John Huston, who was at least thirty years her senior—but as

I've

sprinted through the decades, I notice that I don't even feel comfortable with people my

own

age, let alone those who're older. The post-fifty-five set seems deadened by something or soured by the constant intrusion of reality. I probably project that same ennui to my daughter's friends; they must be thinking,

Poor Grace, the old party animal—she's sitting home again.

Another missed opportunity occurred when Cece introduced me to a very funny and not yet famous Richard Donner, future director of the

Lethal Weapon

movies,

Ladyhawke, The Omen, Maverick, Radio Flyer,

and

Conspiracy Theory,

and the producer of

Free Willy.

He lived in a small, comfortable house in one of the canyons, and I spent an afternoon with him at home, chatting. If I hadn't had that stupid he's-five-minutes-older-than-I-am-so-he-must-be-dead attitude, I probably would have jumped his bones. Happily married now, he's a great director as well as a humane human being, and in his movies he's able to both entertain and inform without compromising either goal.

Hi, Dick! You reading this shit? You wanna make a movie based on the life of an animal-loving, shotgun-toting, eccentric, upper-middle-class rock goddess? No? Okay. Just a thought.

I accompanied Cece to lots of fancy gatherings, where I loved being the only “outsider” in a room full of Robin Leach subjects. We went to a party once where I saw Julie Newmar, an outstanding example of the kind of beauty that drops your jaw. She stood talking to some people in the middle of the living room, and her bright red dress and shoes added to the Nordic Amazon shock value. Standing over six feet, she was taller than most of the men and towered over all of the women. I couldn't imagine what it must be like to be inside such a spectacular body and have a completely stunning effect on everybody within fifty feet of you at all times. There was no costume I could put together to imitate that.

But I

did

get to put on a showy outfit of sorts. Cece got a call for us to be “Kennedy Girls” at a Democratic party fund-raiser for JFK. We wore red-white-and-blue dresses with white straw hats and spike heels, and our function was to mingle, smile, and make the men with the bucks feel like they not only had it, but that if they gave enough of it away … maybe—?

We weren't expected to screw any of them, but we weren't told not to, either. Cece certainly didn't have to do anything she didn't want to do to get wealthy boyfriends, and with my aversion to “old” men, we both managed to go home without putting out anything more than conversation. But for Yours Truly, meeting John Kennedy, even if it was only in a long, fast-moving line of starlet types, was the high point of the evening. This was my favorite summer vacation, and to top it all off, Darlene's ex-boyfriend, Johnny Schwartz, asked me out on a date when I stopped by Palo Alto to prepare for my trip to the University of Miami.

Insignificant events can take on monumental proportions when your head is full of practically nothing.

Convulsive Decision

T

he University of Miami. The humidity dropped me in my tracks (too much cold Norwegian blood?), the palmetto bugs swarmed in red, flying clouds fifty feet wide, splattering on my windshield like blood clots, and everybody on campus was an athlete. But, if you can't beat 'em …

I cut my hair short, bleached it blonde, got a Coppertone tan, wore white shorts and tennis shoes, and learned how to throw a mean shot put. Variety and eccentricity. I also acquired a king snake who stayed in my dorm room and ensured my privacy by being one of the world's least popular animals. In fact, the best athletic move I've ever witnessed was executed by a pudgy girl who, upon sighting the snake, jumped five feet in the air onto the top of my dresser in about one tenth of a second. She was not ordinarily agile, but the snake's presence called forth instant Olympic ability. Encouraged by that performance, I kept the snake, more for entertainment value than an actual affinity for reptiles.

Less intimidating attractions at the U of Miami were plaid madras sport shirts, Cuban music (Castro's fatigue-clad soldiers made up fifty percent of the nightclub clientele), lots of beer and umbrella-topped rum drinks, any sporting event (not my first choice for fun), and a huge linebacker from the college football team. We did a lot of quadruple dating—my dormmates and his teammates—usually centered around movies. Typically, the guys sat in every other seat because their bodies were so big, the normal setup would bring on claustrophobia. Swimming, boating, and attending the obligatory formal prom at the Fontainebleau Hotel completed the list of “must-do” activities. It was a tame and sunny year, during which I remember only two inclinations to deviate from the norm.

The first came when I was in a record store looking for “La Bamba” by Ritchie Valens, and happened to see an album cover with a picture of a guy having a picnic by himself in a graveyard. It was Lenny Bruce. I'd never heard of him, but as soon as I listened to the record, I knew I'd found a soul mate. He used and abused the English language, and he cracked jokes about the Catholic church, Adolf Hitler, the judicial system, and anything else that needed catharsis. In short, he

said

the things that most people only

thought

. When I first heard the album, my face hurt from laughing, and I dragged my friends into my dorm room to listen to this prophet of attitude. Their response was not as enthusiastic as mine, but I wanted to find more people like him to hang out with—fringe-thinking as a way of life.

Look out what you wish for—you might get it.

My second “deviation” was toward a lifestyle change that proved permanent. I received a letter from Darlene that included an article by the

San Francisco Chronicle

columnist Herb Caen. Herb's article was about the new scene—a Bay Area phenomenon that included “hippies,” marijuana, rock music, and strange but pleasantly artistic postbeatnik behavior. Darlene suggested I come home to check it out. Since her instincts regarding promising scenes were always reliable, I decided to return to the West Coast, probably the most pivotal decision I ever made, considering where destiny ultimately took me.

It would be a while before people realized what had hit them, but within a decade, every section of the country would be tossed into the eruption and spit back out with a whole new paradigm to paddle around in.

Stupid Jobs

W

hen I arrived back in northern California in the fall of 1958, I moved in with my parents on Hamilton Avenue in Palo Alto. The first order of business was to find a job so that I could support myself and move into my own place, but what could I do? Neither the knowledge I'd gained at Finch (don't drink your finger bowl) nor the partying skills I'd developed at the University of Miami were much in demand. I scanned the want ads daily, looking for a suitable job and asking myself the same question that had plagued me during puberty:

Where do I fit in?

I decided to apply for a job as a receptionist in a lawyer's office, where multifunctional phones were just starting to rear their ugly little heads. My job was about being polite while trying to remember how many people I had languishing on the hold buttons. I failed—I'm

still

terrible at doing two things at once. After watching me struggle with the advanced technology for a few days, my boss informed me that my “phone manner” was unacceptable.

I remember taking another short-lived job as a market-research guinea pig. After seating me in a dark room in front of a glass case containing three different cartons of aluminum foil, they switched on the light for a fraction of a second. When they turned it back off again, they asked me which box I'd noticed first. The point was to determine which color scheme would best grab the average housewife by the eyeballs and lure her into a spontaneous purchase. Ever find yourself unpacking the grocery bag and wondering why you bought the instant dustball warmer? They've got it all figured out at both the advertising

and

the shelf level.

As I continued to search the want ads, one caught my eye. It read like this:

Singer wanted for new record label. No experience necessary. Call 555-1225.

My mother was a singer and I thought maybe I could squeeze myself into that job, whatever it was. I picked out a song that I loved and dressed to the nines for the tryout. Two men in a small recording studio with a closet-sized control room waved me over to a microphone to do the song I'd rehearsed. Unfortunately it was “Summertime.” For an all-black record label? Bad choice, but I figured it would be worse to attempt a song I hadn't rehearsed. Through the double-glass window of the control booth, I saw gentle smiles—not condescending—just two black men watching a little white dufus squirming under the weight of her own self-inflicted hubris.

I didn't get a callback.

I'd always been a lover of art and I considered myself a fair illustrator, so when an advertising agency placed an ad in the newspaper for a graphic artist, I showed up for the interview, not knowing exactly what a graphic artist was supposed to do. But I explained that I had an idea for updating their Bank of America TV commercials. “How about a cartoon character to liven it up a bit?” I suggested.

“No,” they said. “That would never work. The public doesn't want anything that frivolous when it comes to institutions entrusted with handling their investments. We have to convey the appearance of respectability and reliability.”

I didn't get the job, but on the tube, two months later, I saw a cartoon symphony conductor pointing out the benefits of a Bank of America checking account with his baton. Did they steal my idea?

They

would have said no. After all, I hadn't said anything about a symphony conductor.

How dumb could I get?

Grace Cathedral

W

hen I was five years old, I told my parents, “I'm going to be married in

that

church.” I was pointing to Grace Cathedral, a neoclassical Episcopalian monolith that sits on top of Nob Hill along with the Pacific Union Club (rich guys only) and the Fairmont Hotel. At five years of age, of course, I didn't know what denomination it was, who went there, or anything else about it, but it was big and beautiful, and it had my name.

In 1961, it seemed fitting that Grace Cathedral would be my matrimonial church of choice. My decision to marry was not sudden. Rather, it was a natural progression of events, seemingly the right thing to do at the time. But nothing predictable had real longevity during that turbulent era. My generation, educated by the best public school systems before or since, was busy gathering the ingredients for a cultural stew that would feed reactionary efforts right up through the millennium. So when you consider the diverse mass of information we were receiving during the time period between 1959 and 1962, and the evolutionary shifts that were occurring, it was probably inevitable that my first marriage would be temporary.

My parents, as yet unobstructed by their hedonistic daughter, had moved to a stately, fake Tudor structure covered with ivy and surrounded by ivy-covered neighborhood homes. My mother was doing volunteer work at Stanford Children's Hospital, playing bridge with the ladies, and taking care of my brother, who was a quiet but naturally busy nine-year-old boy. My father was chairman of the board at Weeden and Company, living a polite, unassuming existence. Jerry Slick's parents had become good friends with my parents, and the two families were in the habit of enjoying weekends together at the Slicks' beach house in Santa Cruz. My future husband, Jerry, had two brothers, Darby (author of the song “Somebody to Love”) and Danny (who avoided rock-and-roll silliness altogether). The rest of the Slick family comprised Jerry's mother, Betty, a housewife who drank her way through the family gatherings, Jerry's lawyer father, Bob, and a basset hound.

Our decision to marry was inevitable. Neat and tidy? Not yet aware of what “complete personal freedom” meant, I was evaluating the long-run specifies. Jerry was bright and, like me, twenty years old. We had the same friends, our parents already knew and liked each other, we'd gone to the same schools, had come from the same social strata, had the same ethics and family background, and lived in the same small town. Does that sound like the ingredients for the perfect tight-ass, fifties, arranged marriage? I bought it and so did Jerry.

Was there passion? Nope. Just cultural imposition.

“Will you marry me?” Nobody ever said that lovely, naive line. We just moved into the married state as if it was expected and irrevocable.

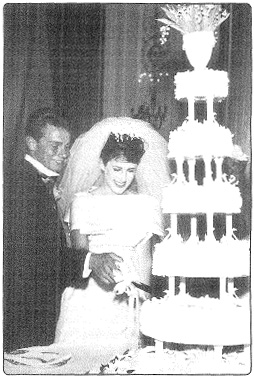

Jerry Slick and I slice through six tiers of tradition on our wedding day. (Ivan Wing)

Even though Cece and Jill St. John didn't know Jerry, my getting married was a good enough reason to get together and knock back a few cocktails. The night before the wedding, the three of us had a low-key, three-woman bachelorette party in one of the bars at the Fairmont. No drunken debauchery, just a mild high to fuel the girl talk. The next day, I had the kind of wedding that women love and men hate—big, dressy, and full of relatives and friends acting out lots of rituals. The reception was held in the Gold Room at the Fairmont Hotel with cake and champagne, and, to me, it all felt natural, no second thoughts, no regrets. Just another workout on the treadmill of tradition coming to a satisfying end at sunset.