Somebody to Love? (5 page)

Over my lifetime—for God knows what reason—I dated a number of guys who'd been with my girlfriend, Darlene Ermacoff. I was thirteen when I had my first taste of Darlene's leftovers. His name was Nelson Smith, and I suppose it still is. You reading this, Nellie? That's what his friends called him. Not only my family but my whole circle of friends seemed to be overly fond of silly nicknames. Like a bunch of rap stars, we wore them with pride.

I invited Nelson over to watch TV one evening, and since the set was in the dining room, we had to sit in these two stiff-backed chairs. I was so preoccupied with

him,

I have no idea what we watched; it could have been

Howdy Doody

for all I cared. All I remember is that it took him a tantalizing two and a half hours to get from the position of simply having his arm around my shoulders to dropping his hand and lightly caressing my breast. We kissed a couple of times and since I hadn't yet heard of “hard-ons,” I didn't realize what kind of pain a two-and-a-half-hour erection was probably causing him.

Teenagers' sexual advances—or lack thereof—are fraught with such intensity it's amazing they don't regularly culminate in a big blast of hormone-driven shrapnel.

Fat

I

n the early fifties, my father got a pay raise, so we moved from our small, rented San Francisco house to a larger, two-story home in the suburbs. Palo Alto, home of Stanford University, was a college town that provided a safe and proper environment for bringing up well-adjusted (?) children. Suddenly, we were right in the middle of the WASP caricature of family life, complete with two children, a two-story house, a two-car garage, and the promise of many more “well-adjustments” on the horizon.

I didn't mind our move as much as I minded my parents selling our old black 1938 Buick, my fat friend that lived in the garage. They just went and

sold

it—the car that had faithfully transported us since I was born. Although crying was something I rarely indulged in (I usually got either quietly annoyed or verbally abusive), tears flowed for my intimate four-tired friend. I was sure that cars had feelings. It just seemed such a betrayal that a 1949 two-tone gray Oldsmobile was now usurping the Buick's position as a member of the family.

Still, Palo Alto was interesting enough—not exactly Barnum and Bailey, but for a ten-year-old, it was at least accommodating. Unlike in hilly San Francisco, the roads here were flat and you could ride a bicycle all day and not get tired. And was it peaceful. For the first time, I could pretty much go anywhere I wanted and my mother didn't have to worry.

I was rarely alone, though. I met two girls several days after we moved in who would be my pals for the next couple of years. They were into a more athletic style of play than I ordinarily favored, but since neither suggested going to a museum and I wanted to have friends, I took up handstands, cartwheels, hide and seek, swimming, and roller skating. Unconsciously, I was beginning to learn about social groups and the hierarchies that inevitably sprung from them. There were the cool guys and the nerds, and I quickly realized that I was going to have to shed the nerd cocoon if I wanted to be part of the pack.

It was time to start letting go of individuality. Lose the art books, get into Marvel Man comics, take off the saddle shoes and get some flats, never mind Chopin, check out Chuck Berry, adults are a drag, kids rule. Are you too fat? Is your hair the right style? Here it comes: the big teenage mold. The big question was: DO I FIT IN?

And then there were

boys

. In 1950, when I was ten, Jerry Slick, one of my neighbors, was in my sixth-grade class. I thought he was a dufus with his round face and glasses, but then, in 1961, I married him.

So much for the judgments of a ten-year-old.

Now Red Hendricks—

he

was another story. He was cool and dangerous, a member of the “fighting Irish,” with a knocked-out front tooth, a greased-up fifties pompadour, and a heavy attitude under a black leather jacket. Too bad I was a fat dufus myself. He wasn't interested.

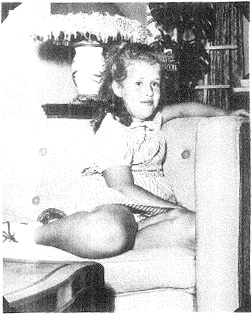

Fat blonde doing a Sharon Stone exhibition: me at nine. (Ivan Wing)

I remember another kid, named Ricky Belli (his dad was Melvin Belli, one of San Francisco's flashiest lawyers), who lived down the street. He and my friend Susan used to make out in his garage. Did they go all the way? She said no, he said yes. But no one pulled

me

into any garage fun. There were no debates about whether

I

had gone all the way. No one raced after

me

when the kissing games began.

Something was wrong with my picture: braces and fat, for starters.

I arrived on the first day of class at Jordan Junior High School, wearing the wrong clothes and the wrong hairdo, with the wrong binder and a complete lack of teenage skills. But I

did

notice the girl with the blonde hair, big smile, big boobs, long legs, and cool outfit. She's the one, I thought. It was Darlene Ermacoff. I knew she'd graduated from one of the other grammar schools closer to the center of town, where the kids were more sophisticated. Her boyfriend, Johnny Schwartz, was good-looking, dark haired, and slender with a great smile, and his father, “Marchie” Schwartz, was the Stanford football coach. When I watched Darlene and Johnny strolling by, I knew I was looking at high school royalty—the king and queen of the prom. So I got the clothes, the shoes, the binder, and the hang of the way to talk. And since I was blonde, I figured as soon as puberty kicked in, Darlene and I would be neck and neck in the Barbie doll marathon.

But something went wrong. At thirteen years old, my hair turned fuzzy dark brown, the large boobs never materialized, and after the weight dropped off, I was nothing more than a skinny, sarcastic, dark-haired basketball cheerleader. What I didn't appreciate at the time was the wonderful workout a woman's imagination gets when she can't rely on her looks to make it all happen. She has to be ready for contingencies, and she knows that any acceptance she

does

get is a compliment to her creative ability, not her genetic code.

Smiling through the transition: me at thirteen. (Ivan Wing)

But that “silver lining” didn't mean shit in high school.

Darlene was one of those girls who had it all: good code, good humor,

and

a good mind. We became friends, anyway, and a couple of months ago when she was staying at my house for a few days, I asked her why she'd stooped to hang out with my nerdy self. We were laughing about the phases, the years, the mistakes, the boys/men, the death-defying drug use, the whole diary, and she said she'd thought that

I

was the pretty one, the clever one, and so forth. If only I'd known that in 1952. I don't remember feeling like a

total

loss back then, but until I was about twenty-four and saw myself as a social steamroller, there was always this intangible next step that needed to be taken to feel like I had the situation locked.

A step I could never quite manage.

So having become at least a second-string member of the ruling social class at junior high, I let the family flag of sarcasm fly in all directions. I figured my mouth was all I had, that my sarcasm was my way

in

with the popular girls. And everything seemed to be going relatively well, until the night of my fourteenth birthday. I was at home, celebrating with my family, when my girlfriends called me up. I ran to the phone excited, figuring they wanted to wish me a happy birthday. Instead, they told me that my lack of consideration for other people's feelings—aka sarcasm—had led them to the decision to drop me from the group.

No friends?

Tears. My mother had a diamond ring I'd always loved, and when she saw my sadness, she gave me the ring in an attempt to snap me out of it. Diamonds as a substitute for friends? The ring did nothing to cheer me up, and I realized that this bauble I'd coveted for so many years was now nothing more than metal and minerals.

Did I learn anything from the experience? Not really. People are only occasionally more important than metal, minerals, black humor, and cars.

Stubborn.

Blue Balls

N

ineteen fifty-five. I was a fifteen-year-old sophomore at Palo Alto Senior High School, and I joined a girls' club to get in the swing of things. On initiation day, I was blind-folded by the other girls and told to take my blouse off and put it on backward. Oh, shit, they'll see the Kleenex stuffed in my bra. But nobody said anything. Were they too polite or was the bra too dense to see through? I'll never know.

Girl-ask-boy dance. Okay. I went straight to the top by asking the school's star quarterback to be my date. He was older and he didn't know who the hell I was, but he said yes. Polite, I guess. I bought a pink, flower-covered, wedding cake-like monstrosity of a dress and went with Mr. Hotshot to a pre-dance party thrown by a senior cheerleader. She opened the door in a red, body-hugging floor-length number with four-inch dangling earrings, which made me look like an exploding cotton candy machine. After the evening, when I asked my mother what she thought of my “catch-of-the-century” date, she remarked, “He's not very bright, is he?”

No, but were brains really the point?

I was a flat-chested fifteen-year-old sophomore trying to impress myself and my friends by pulling in the school jock. This was not about brain surgery. On a Friday night, a few hours before another dance, I ripped off a fifth of bourbon from my dad's basement stash, and my friend Judy and I polished off the whole bottle. She passed out; I thought I was Betty Grable and went to the party with a Catholic boy who smelled like fish. (That's all I can remember about him.) I sprayed perfume in my mouth so nobody would notice my breath, but of course, it didn't work. I danced like a puppet, thought I was Ginger Rogers, stayed up all night, and threw up all the next morning.

Did I learn anything from the experience? Not really. I figured it was all in how you weighed it: how much fun you had balanced against how much you had to suffer through in the morning. I loved getting high, so I paid the price.

You want a Rolls Royce? You gotta pay for it.

During school breaks, we'd all pile into someone's car and go to a drive-in for burgers, gossip, and boy watching. I gravitated toward Judy Levitas. At age sixteen, Judy had her own car, and instead of going to public school like the rest of us, she went to Castilleja, a private school for girls. She wasn't as judgmental or as enslaved to teen peer-pressure rituals as most of the girls I knew, and I liked her easygoing way of looking at things. Judy, who had very understanding parents, often had a bunch of kids over to her house on the weekends to party and swim in her pool. She gathered boys from Catholic school, boys from Palo Alto, boys from Stanford, and boys who'd dropped out of school to work on cars, along with girls from many different backgrounds and locations—a good mix.

It was at one of Judy's parties that I met my first love, Alan McKenna, a Catholic school boy. He seemed to be holding court on the other side of the pool, and although I couldn't hear what he was saying, I guessed from all the giggling women around him that he had a personality to go with his good looks. When I got closer, his green eyes surrounded by thick dark eyelashes nailed me to the air. I was hooked and we became a steady couple.

Alan and I used to do some serious necking, sprawled out on the backseat of my parents' brand-new 1955 Oldsmobile. He knew how to make me laugh and he inadvertently gave me my first string of orgasms, although not by penetration. In the missionary position, when he had his clothes on and got hard, his penis was in the perfect position to massage my clitoris, so with both of us fully dressed, I was getting off every time. But he was getting “blue balls.”

“What,” I asked, “are blue balls?”

He explained that a prolonged erection without release gets to be painful. Since none of the so-called nice girls went “all the way,” and for many of the Catholic guys, masturbation was considered a sin, there were a lot of Pope-restricted teenage boys running around with bad cases of blue balls. Now that

might

have produced a sufficiently large guilt trip to sway me into having some real sex—but I didn't go for it. In hindsight, screwing Alan McKenna, somebody I liked, would have been a better choice than the one I made. But I was dumb enough to do it the first time with somebody who didn't mean that much to me—when I was drunk.