So Many Roads (26 page)

Authors: David Browne

Fruitful, but also occasionally brutal. In another groundbreaking move the Dead never played quite the same setâor played it the same wayâtwice. The results could be transcendent or at times chaotic. “Jerry would rush, and things would pick up when Jerry played fast,” Rock Scully says. “Phil would often turn his back on the audience and be so disgusted that things hadn't gone his way. Jerry would yell to Bob, âKeep it simpleâyou're losing them! There's value in the silences!' Jerry's rushing, Phil's not always keeping that bottom bass happening, leaving it up to Billy's foot. It all mixed together into a great series of near catastrophes.”

Listening back collectively to the recordings after shows, the band would assess those recordings and try to learn from them. “We used to sit and listen to everything we did and kick it around,” Weir explained to

Rolling Stone

after Owsley's death in 2011, “and say, âI'm not gonna do thatâthat didn't work,' or âYou hear that accident in there? Let's make something from that.' That came from his tapes. We questioned everything

we

did. He instilled or reinforced in us quality consciousness. If you're going to do something, you have to absolutely achieve excellence and set your internal compass toward excellence and go for that, because nothing else matters.” The process, though, could be rough. “There was always something somebody complained about,” Constanten remembers. Even the people who taped the showsâwhich,

starting in 1970, included Candelarioâweren't spared. “After the show everyone piled into your room,” says Candelario. “All the band members and road crew, everyone smoking and drinking beer, and you'd better damn well have recorded everyone's part or else they'd complain about you. They were discussing the music and chord changes, and they'd bring out that someone wasn't playing the part and put the blame on you, that you hadn't recorded it. You were always under the gun.”

As Lesh learned during this time, that sense of impatience and perfectionism, much of it coming from Garcia, could also rear its head while they were playing. At a Carousel Ballroom show in early 1968 Lesh was still so rattled by the passing of Neal Cassadyâwho'd been found near death beside some railroad tracks in Mexico, apparently after he'd attended a particularly wild party, and passed away soon afterâthat his playing stumbled and stopped, and he caught sight of Garcia staring harshly at him. After the show Garcia expressed his unhappiness even further by either knocking Lesh down or shoving him hard. “That was almost funny,” Lesh recalls. “It wasn't threatening. I knew that he never did shit like that, and we were all chemically altered at the time. I knew the next time I'd see him he'd be apologetic, and he was.” (McIntire would later remark how genuinely startling it would be when Garcia's temper would flare up from time to time.)

The exchange between Lesh and Garcia was more physical than most encounters between the Dead, but moments like those were now part of the band's gestalt. For every moment of shared group bliss, musically or chemically, came one of tough self-analysis. As long as it paid offâif the musical peaks were reachedâthen the hardships were worth it.

At early shows like that, friends like Vicki Jensen would take in the full exploratory power of the Dead. “A piece of their music would take you on a journey, with each musician creating a variety of threads that would magically weave together in sound and movement that would

take your breath away in total awe,” she says. “I'd look around at everyone else standing behind the amps with me and the audience, and I could see everyone was totally synced. I would see the musicians' faces, and I could see they were so completely loving what was happening in each moment. And as all the sounds came back together for that piece of music's finale that made your soul feel as if it had come homeâand looking at their faces and the surrounding energy still crackling from what had just been playedâI could see that they were as amazed by what they had created as we who got to hear it.”

Twenty-five minutes into what would become one of the longest-ever renditions of “Dark Star,” the music began to calm down, like a rain shower that followed a hurricane. Kreutzmann and Hart put a damper on the beats, Constanten soothed his organ, and Garcia took a breather from his frenetic freeboard thrashing. Just over a minute later Lesh resurrected the long-vanquished “Dark Star” opening notes, and the rest of the Dead took that as a cue to return to the song's central motif. Twenty eight minutes in, Garcia began singing again, and an island of calm returned. With that the song took a graceful bow and came to a close. In the last few moments of “Dark Star” they made peace with the song and with themselvesâknowing full well that the tumult could all start up again at any moment, and probably would.

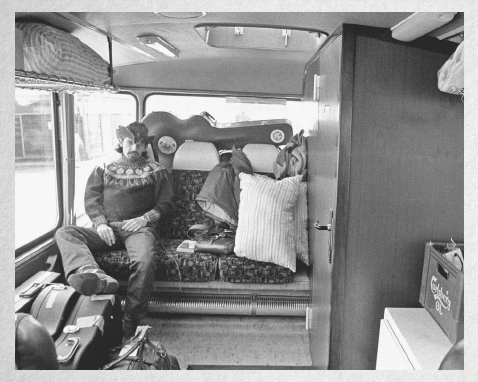

Pigpen on the Europe '72 tour bus, Copenhagen.

PHOTO: JAN PERSSON/REDFERNS/GETTY IMAGES

On the other side of the thick steel door came a loud voice barking out a concise, unmistakable command: “Back

off!

”

The drunken or stoned kids who'd been banging on the back door of the Lyceum Theatre in London were about to learn an important lesson. They should have known the area around the stage at any Dead show was, in tour manager Sam Cutler's phrase, “sacred space,” and they should have known better than mess with the Dead's formidable crew. But they hadn't been aware of any of those tenets, and just as in the other European countries that spring of 1972, they were about to receive a lesson in when one did and didn't mess with the Dead.

Although the Dead were fifty-three hundred miles from home, one aspect of their world remained the same: Betty Cantor was recording their shows and making sure every note of every performance was skillfully preserved on tape. This time she was in a truck behind the Lyceum, a ballroom that dated back to the previous century. Tucked away on the north side of the Thames near Covent Garden, the Lyceum was past its expiration date, but the white columns at its entrance and the

dance floor in front of the stage were reminders that it had once been a swanky dance hall. (Cutler recalls the walls looking like “all gold leaf and crumbly wallpaper.”) Not that Cantor could see much of the hall or its surrounding neighborhood. In order to record the Dead's first-ever tour of Europe, the band had rented a truck and converted it into a mobile recording studio, and Cantor had to squeeze into its cramped space and supervise the recordings with the help of her colleagues Jim Furman and Dennis “Wiz” Leonard.

The tour was almost overâonly one more show remained before they'd all fly back homeâso the night should have been relaxing. But then came the clamor, the shouting, and especially the banging. Something was slamming into the truck, and Cantor was reeling. “What the

hell?”

she thought. It was, she says, “like being inside a bell when it gets banged on.” The sound was so rattling she was afraid to open the door and look outside, and all she could do was call her fellow crew members from inside the truck with a simple message: “Something's going on!”

Buddy Cage had seen it coming. The Dead's opening act at the Lyceum was the New Riders of the Purple Sage, which had started in 1969 as a Dead spin-off when Garcia and singer-guitarist John “Marmaduke” Dawson, an old friend from the Palo Alto days, had formed an ad hoc band built around Dawson's hippie-country songs. Unable to dedicate himself fully to both bands and aware of his limitations as a pedal steel player, Garcia had recommended Cage for the slot during the multiband 1970 Festival Express tour of Canada (Cage was a member of the Canadian folk singing duo Ian and Sylvia's band at the time). “He said, âI stinkâP.U.,'” Cage recalls. “âYou gotta be the guy to take it.'” Thanks to a contract with Columbia, the New Riders, which also featured another longtime Garcia pal, David Nelson, on lead guitar, were now their own men, playing stoner Bakersfield country rock that had a growing cult following.

As the Dead played on at this penultimate night at the Lyceum, Cage seated himself on a set of stairs in full view of back doorsâeach the size of a bay windowâthat opened to the area behind the theater. He'd already seen the ushers escort four or five rowdies out of the theater, and now he, like Cantor, was hearing them trying to make their way back inâscreaming, pounding on the door, and taking their anger out on the Dead's truck. Cage wasn't the only one to hear them; soon enough so did Rex Jackson.

In the four years since he'd driven down from Oregon, Jackson had become an integral part of the Dead's crew. He'd shared a house with Cutler; fathered a child with a new member of their community, Eileen Law (a daughter named Cassidy); and commanded the respect of his fellow crew members. When Jackson wanted to put an end to any trouble in the Dead world, be it in the crowd or backstage, all that was necessary was a simple gesture. “He'd poke one finger into the solar plexus, and they'd know, âOkay, I'd better not take this any further or my ass is grass,'” Cantor-Jackson says. “He was very intimidating on that level.” Tonight, though, one finger alone wouldn't do the trick. With both the show and the truck in danger, Jackson took a moment to size things up: he looked up at the doors and the cables that held them in place, rubbed his hands together, and proceeded to lift one of the massive doors right off the cables. As Cage recalls, he was “like a big steed, but far more agile.”

Moving that part of the door to the next section, Jackson created a portal to the outside. Seeing this hairy mountain of a man before them, the Brits were momentarily stunnedâ

what kind of creature was this?

, they surely thoughtâand barely had time to absorb what was happening before Jackson dispensed with them. Precisely what happened remains unclear. Cage says he punched the kids out one by one, leaving them sprawled on the ground; Steve Parish, then into his second year as part of the crew, remembers the gesture being more intimidation

than anything physical. (“Jackson yelled at them, and they ran down an alley,” he says. “There was a rowdy scene, but he didn't hurt anybody.”) But no one doubts that, after ten or fifteen minutes, the hooligans were no longer an issue. Jackson was, in Cantor-Jackson's words, “my hero,” and Cutler says it was another example of Europeans encountering what he calls the Dead's “California western robustness.” Dozens of feet away the Dead continued playing, oblivious to what had happened.

No one intended it that way, but the brawl, hellacious or not, was a symbolic final exclamation mark. The Dead's nights at the Lyceum were the end of a trip that demonstrated the musical might of the band to those outside the States; shored up their new, revised lineup; and cemented the power and authority of their crew. But it was also a trip that would forever rattle their original lineup and more than few personal relationships. The Dead who would board planes to return to Marin County not long after the last notes at the Lyceum faded would emerge from it all a very different band, in ways both settled and unsettling.