So Many Roads (21 page)

Authors: David Browne

At Barrish Bail Bonds, right across from the San Francisco Hall of Justice, owner Jerry Barrish, who had a reputation for coming to the aid of antiwar protestors, students, and the underground, gave them $500 each for their bail and didn't demand immediate repayment. Later they learned more about what had happened: Snitch had been threatened by police for alleged offenses if he didn't cooperate with them, and he had little choice but to turn them in. Soon after Mountain Girl handed him the pot, he turned it over to the authorities. For decades after, Weir would have the feeling that the band had been set up, the pot planted.

Those who were already living or crashing at 710, like Rifkin, Swanson, and Weir, made their way back to the building. “It was odd,” says Swanson. “It was like coming home after your house had been robbed.” Again they congregated in the kitchen, and the first order of business was disposing of the craggy brick of pot still partially tucked away in

the kitchen cabinet. “We got that out of the house immediately,” says Mountain Girl. “There was a great cleanout.” One rumor had it that it was transported across the street to the neighboring apartment where Garcia and Mountain Girl had holed up during the raid; at the very least it was out of their home in case the police returned.

In the hours and days that followed, everyone attempted to resume as normal a life as possible, but a lingering sense of paranoia and apprehension settled over the building for the first time. The vibe, as Mountain Girl recalls it, was “a lot more edgy. It was, âCool it for a while.'” They didn't

quit

smoking, of course; they simply reverted to doing it in the upstairs parlor, out of street-level sight, not leaving any extra pot or roach clips lying around. “Before that, we had joints hanging out of our mouths all day long,” says Scully. “They'd go out like a stogie and just hang there. But we got a lot more careful.”

When the raid was in progress someone had tipped the nearby offices of a new magazine about to launch,

Rolling Stone

. Jann Wenner, the twenty-one-year-old who was its founding editor, had his own personal history with the Dead. He'd dropped by one of the Acid Testsâwatching them play in the large bay window at Big Nig's houseâand had written about the Trips Festival in his column for UC Berkeley's student newspaper,

The Daily Californian

. Wenner had loved the Dead's first album; in Swanson's memory Warner Brothers sent out a copy of

Rolling Stone

's imminent first issue to everyone in the band's fan club.

When Wenner heard about the arrests he immediately dispatched his chief photographer, Baron Wolman, to shoot the band and friends at the bail bonds office. Although he knew it was a major story, for both the city and the local music community, Wenner scoffed at the raid itself. “It was more like the Keystone Kops raiding the Dead,” he says. “The Dead were just laughing about it.”

The arrests and their lingering, sour aftertaste didn't drive them out of the Haight immediately, but it was the most distressingly apparent sign that the neighborhoodâand their time in itâwas coming to an end only about a year after they'd all moved into 710. “It was one more stick on the bonfire that was consuming the Haight,” says Mountain Girl of the bust. “It was making it less than fun. Jerry and I both felt pretty uncomfortable being there.” The Summer of Love media hype had been eye-rolling enough, as were bad-trip faux-psychedelic pop hits like the Strawberry Alarm Clock's “Incense and Peppermints.” (Granted, the Strawberry Alarm Clock wasn't that different from the alternate names the Dead had kicked around before stumbling upon their ultimate moniker.) The sightseeing buses that began driving though the Haight were amusing at first. The Dead and their camp made absurd fun out of the tourists gaping at their home: Pigpen mooned one bus, and at the band's urging during a visit Warner's Joe Smith ran up to the top of the street and whistled when a bus approached so that everyone at 710 could hide, depriving bus riders of any sightings.

The bust was far from such goofy fun; instead, it was proof that the eyes of part of the world were now upon them. “It was a reminder that what you did was illegal in nature and there were consequences involved in that,” says Jefferson Airplane's Jack Casady, who rolled the joints at a 710 Thanksgiving dinner in 1966. It was also another sign that a darker side of the Haight was revealing itself. Runaways were showing up more regularly, people were tripping and stepping out of top-floor apartments and splattering themselves on to the sidewalks, and harder drugs were dirtying up the neighborhood. The latter problem was more than reinforced to the Dead when they learned of the murder of William Thomas, an African American drug dealer known as Superspade. Scully had known Superspade even before he'd met the Dead. (Scully himself would sell hash periodically to help pay the rent, both at 710 and the house he previously lived in.) With his flamboyant wardrobe, Superspade was one of many local characters, but two

months before the bust at 710 his body was found shot, stabbed, and stuffed into a sleeping bag that was hanging off a nearby cliff. Shortly before that grisly discovery another local dealer, known as Shob, was stabbed to death a dozen times with a butcher knife, and part of his right arm was hacked off.

The Haight was on the periphery of a high-crime area, and some thought Superspade simply wasn't being discreet enough (he had a tendency to flash wads of bills in public) and had probably found himself in a turf war. Either way, his brutal killing was a sign that the dealers in the Haight had become murderously territorial, each fighting to make as much money as possible over the dazed teenagers burrowing into the Haight in the wake of the Summer of Love. “Superspade was a really calm, really nice dealer who we trusted,” says Hart. “No one would want to kill him. When that happened, that put a big shock in me. The mood on the street was turning ugly. People were getting stoned for no reason and people were going because it was an âattraction,' like Disneyland. The world was closing in on us.”

They had to start thinking about leaving, and the signs were already in the air that it was happening. At Scully's invitation, Stan Cornyn of Warner Brothers had flown up from Los Angeles for a meeting at 710, and Cornyn was finally able to walk up the fabled front steps he'd been hearing about. Someone let him in, and he took a seat in the living room and waited. And waited. And waited some more. He sat taking in the sights, especially a black-and-white photo of a naked girl facing a naked boy. “Hippiesâwow!” Cornyn thought. “It was so much nicer than what I was doing.” But no one ever came out to talk with him, and he was eventually told that maybe they were asleep. Cornyn had no choice but to leave.

Three days after the bust came one of the Dead's last great escapades at 710. At Gleason's suggestions, they held a press conference at their

ransacked home. Beforehand Rifkin expressed what he wanted to say to his former UCLA classmate Harry Shearer (later an actor and comedian known for his work on

The Simpsons

,

This Is Spinal Tap

, and

Saturday Night Live

), and Shearer, who would often visit 710 on weekends, helped Rifkin write it out. Flanked by the band members, Garcia smiling gently, Rifkin called pot “the least harmful chemical used for pleasure and life enhancement,” decried pot laws as “seriously out of touch with reality,” and derided the media's image of the “drug-oriented hippie. The mass media created the so-called hippie scene. . . . The law creates a mythical danger and calls it a felony. The result is a series of lies and myths that prop each other up. Behind all the myths is the reality. The Grateful Dead are people engaged in constructive, creative effort in the musical field, and this house is where we work as well as our residence.”

A bowl of whipped cream, a spoon jammed into it, was placed in front of Rifkin, but it wasn't meant for any sudden attack of the munchies. The band decided that the first reporter who asked, “How long did it take to grow your hair?” would get pied. Luckily, no one was brave enough to toss out that question, and the dessert remained untouched. Among those at the event were

Rolling Stone

photographer Baron Wolman. At thirty, Wolman was older than most of the subjects he'd begun shooting for the nascent magazine, and he never got high (he preferred the roller derby over acid). But he had a way of putting his subjects at ease (the ever-caustic Grace Slick would happily pose for him in a Girl Scout uniform), and he respected the new style of rock 'n' roll. Even with his innate bedside manner, Wolman found himself in a challenging situation at 710. He watched the press conference, and the band seemed, in his mind, “weirdly elatedâthey were so high, on a natural high, over the message they were giving.” Because

Rolling Stone

didn't yet exist and he had no business cards, Wolman had to convince Scully, Rifkin, and the band of his legitimacy.

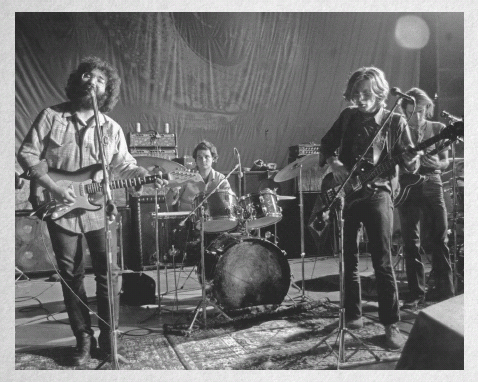

For his photo shoot Wolman asked for a group pose, but between their energy and agitation, it was hard to corral them all. After the conference was over the bandâwith Sue Swanson and Veronica Barnard yapping away in a nearby windowâwas asked to gather on the stoop, and Wolman sensed his one chance had arrived. Kreutzmann flashed a middle finger, and Pigpen and Garcia goofed around with an antique Winchester rifle that Scully had found on a trip to Mendocino. The gun was so broken it couldn't have fired even if it had ammo, but Wolman was still unnerved. “I was slightly worried they were going to do me bodily harm,” he recalls. “Had I been close to them and part of that coterie, I would've been much more comfortable with what was going on. But I was happy to shoot them on the stoop and get the fuck out of there before I got killed.”

As Wenner had predicted, the bust didn't amount to much in any legal sense of the word. In the end Scully and Matthews pled guilty to a misdemeanor charge of “maintaining a residence where marijuana was used” and were fined $200 each, while Pigpen and Weir were each fined $100 for being in a place where the drug was used. “The DA said, âLook, how about if you guys plead to the lowest possible health and safety-code regulation it could possibly be?'” recalls Stepanian. “I said to them, âWhat do you think about paying a fine?' They said, âNo jail? Fine.' Here's a hundred bucksâsee ya later, good-bye.” All were put on probation. It was time to leave the Haight and strike out elsewhere in search of new homes and adventures. But as their defiant pose on the stoop showed, that bust and its aftermath came with an unexpected bonus: it proved that, though they weren't above the law, they might be able to live just outside itâand endure.