Sleight (2 page)

Authors: Kirsten Kaschock

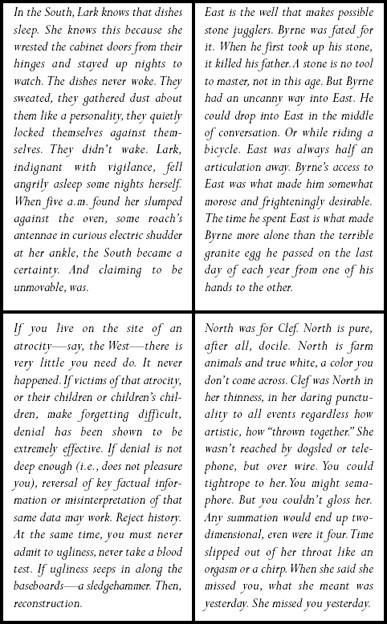

A NORTHERN.

W

hen what happened happened years ago, it happened quickly, and Clef had no time to care who was hurt. She took Kitchen from Lark. There were no jealous seeds. Clef, after all, had been the prodigy. At the time, they were all friends together in the same troupe. Kitchen was old, like a god, but they were all friends; Clef and Lark even had the semblance of best. As sisters, they were no such thing, but the semblance couldn’t be denied. Clef took Kitchen from Lark because it caused pain, one of the primary substances. An original thing the world makes happen.

The metal door eked out a small intrusion (Clef made a note to prop it during performance), and there stood bright-morning Haley, a vapid bit of talent Clef could barely stomach, and not this early. Haley tipped her hotpink bag from a shoulder onto the nearest chair—a sloping gargoyle of kelly green plastic.

“Hey Clef, what’s up?”

“Not so much.” Clef was stringing together a new architecture with fishwire. It was only a few lengths long, but its configuration would create whole other potentials. The fiberglass tubes were transparent, as was the fishwire, which used to be intestines, and the tubes glass, of course, and fragile. Blown glass was still used for some opuses—the earliest works required a complexity of resonance. Recent materials (this was universally acknowledged) offered lesser song, but the control they gave the sleightists was astonishing. The best sleight, Clef thought, must hang somewhere between balance and exchange.

She could feel Haley waiting for her to look up. Angry at being interrupted and then telling herself she had no right, Clef tried to be civil—not looking up but raising her eyebrows expectantly. Evidently, this was enough.

“Did you see those awful billboards?”

“No, I slept most of the way across 80. Because of the corn.” (Pause.)

Haley was going to make her supply the line. Clef sighed. “Awful how?”

“I mean, what were they were selling? I thought maybe God shit—this is the Midwaste.” Haley was from New York, and not the state.

“You’ll have to tell me what they said before I can speculate, Haley.” Clef pulled out nail scissors to trim the wire.

“They said ‘you are living on top of an atrocity’ or something. There must’ve been ten of them.”

“Not, I think, about God. Could be Native American.” Clef considered types of atrocities she might have lived on or driven near the grounds of during her lifetime: massacres of indigenous peoples, extreme cosmetic surgeries, executions of Chinese sojourners, rapes, terrorist bombings, genocides, suburbs, Three Mile Island, forced sterilizations, plantations, serial murders, baptisms of the dead, severe and avoidable industrial accidents. Clef had always liked being informed. She’d audited a couple of classes at Harvard while at the academy before realizing just how deep ran her loathing of paralysis.

“Is there a reservation around here?” Haley smiled. “I love roulette.”

Clef couldn’t help it, she had to strike the bunny. “You know, Haley, reservations are where people were driven after their families were massacred and their land was stolen. And I’m using the word ‘driven’ as in cattle—not taxi.”

Haley, smile dropped, looked for it on the linoleum. “Right.” Haley, none of the troupe, much liked this part of Clef.

Clef attempted not to care, couldn’t manage, so eased up. “What did everyone else think?”

Haley took a few moments tersely upsweeping her flounce of bottle platinum. Clef’s red was her own—her hand briefly left her architecture to grip a length of it. Still wet enough to braid.

“Mostly the troupe thought God shit. But Kitchen said it might be a car ad.”

“A

car

ad?”

“Remember how Infiniti ads didn’t tell you what they were at first?”

Clef nodded but couldn’t stay quiet. “Only they didn’t reference mass murder or genocide. Antagonism as a consumer strategy—not sure that’d—”

Haley, fishing bobby pins out of the side pocket of the hotpink, cut Clef off. “C’mon Clef, you of all people know Kitchen—he has a take on everything.”

Clef stood up—she was barely a tick over five foot. She slammed her architecture against the cinder-block wall eight or nine times to make sure it was secure.

“Yes. He has his takes.”

A WESTERN.

W

est is drift. West is sink and heal and halo. West is following orange all the way to whiskey. West was born West. But perfection being direction, not destination, he felt what he eventually worked out to be too much pressure. West, at three, knew he was a miracle. You don’t get to be a miracle without knowing it early on. West took other names: Huck and Fret and Sin. Settled on Drift. Called himself Nomad-for-Hire. West was all about calling himself. That’s how West got to be a religious, by working both sides of divinity.

AN EASTERN.

B

yrne had been lullabyed beneath a tool mobile. A real wrench, hammer, Phillips and flat-head screwdrivers hung above his crib, and later from the defunct ceiling fan in the attic room he shared with his younger brother Marvel. Their father had wanted capable sons, sons who could fix a dishwasher, a dryer, a slow drain—sons for whom pleasure would come from the engines of cars.

When Byrne’s mother skirted him and his brother along the edges of their father and off to the theater, it opened a geyser in him. It wasn’t that the last defiant seed of her identity was contained in that act. It wasn’t the cinema of murmur—the hush, then black. It wasn’t even the sleightists: their tatted webs glinting against then obscuring their limbs, their perfect, blank countenances as they braided through one another. Nor was it the shock of seeing his first structure: helical then crystalline then “clotted,” as “clotted” is indistinguishable from “containing life.” For Byrne it was the words—the beginning of the sleight that most of the audience took like a vitamin. The words became the crime to Byrne in its entirety.

Byrne invited a girl up to his one-room.

“A drink?” Byrne headed to the mini fridge in the corner.

“Sure, what’s in there?” The girl looked comfortingly like all other girls.

“Vodka, juice.”

“What kind?”

No answer, Byrne one-handedly poured the drinks into two coffee mugs, brought hers, went back for his.

“Cheers,” he said, lifting his drinking hand.

The girl tried not to look at the other one, the one clutching. Instead she tried recovering, tried trying out coy. She cocked her head, or tossed her hair, something before she spoke. Byrne didn’t quite catch what.

“Cheers? What for?”

“For fellows, flowerbeds, muskets, olfactories, sects, flowcharts, squirrels, plots, deceits, blemishes, carp, blocks, barkers, sidereal freaks-on-fire.” Byrne listed these absently and she giggled, uncomfortable, thinking she recognized this wasn’t a joke.

Byrne wasn’t really that way, not clinically. He was verbally sketching a precursor,

2

already bored and close to forgetting her there.

After she left, Byrne walked down to the corner cigarette, malt liquor, candy, diaper, and milk distributor. He bought a six-pack and some beef jerky, then sat on a bench maybe halfway back to his apartment. He held a can of ginger beer under one arm while he opened it, then shoved the jerky into his mouth and took out a pen and a folded index card from his shirt pocket. Once settled, he started composing on his thigh with his eligible hand. He was stuck on a string of words he attributed to the influence of the billboards. There was some disagreement online, but the first one had probably appeared almost a year ago. Some said outside Fairbanks, others insisted Wyoming. Now they were all over North America and Europe, Japan and India. All of the speculation centered on the author’s identity. If there was urgency, a dire reason for the Gatsbyesque post, very few seemed to care what it might be.

Byrne didn’t know why he bothered writing. If you weren’t a hand, you couldn’t write precursors. They were supposed to initiate the sleight. In truth, he shouldn’t call what he wrote precursors—at best his work mocked. Precursors were supposed to pave the mind for a sleight, to bring the audience to capability. His did nothing close. They linked to nothing.

I make overtures to nothing

—it was a pathetic obsession. His father would’ve said, “I knew you weren’t a man.”

When Byrne had begged to take, his father had said sleight was for academics, which was a crock. Gil Dunne hated intellect, which he assumed was some kind of affectation, some trick. So no. That was it. Byrne was six then seven then eight, a hating child learning carburetors. His mother used to sneak him and Marvel to the theater before Marvel started telling. Byrne never liked cars. He didn’t like working-class. His brother was anathema. And then he picked up his rock.

3

2

Before every performance one of the sleightists takes the stage. The word-list the sleightist recites is called the

precursor.

In the first works, the precursors had actually been written as marginalia, arrayed vertically alongside the diagrams. The choice to have the words recited prior to the performance rather than spoken concurrently with it is an established one. Lately, that tradition has come to be challenged by a radical troupe known as Kepler.

3

Some ancient American hieroglyphs contain depictions of “stone jugglers”; some of Revoix’s original sleight structures seem to reference these forms. The figures are invariably shown with downturned faces and with one hand raised into the air, cupping a single rock. Initially, archaeologists thought this rock was a sacred object, perhaps even an original thing. But after enough ruins were stripped bare of their jungles, comprehension—even for archaeologists—was inescapable: the figures holding the stones were the center. Although their presence is integral to the calculations of time and shame in which they are found, the jugglers are separated from other carved forms (healers and mathematicians). Indeed, in pictographs with very little space wasted, left around the stone jugglers is a silent periphery.