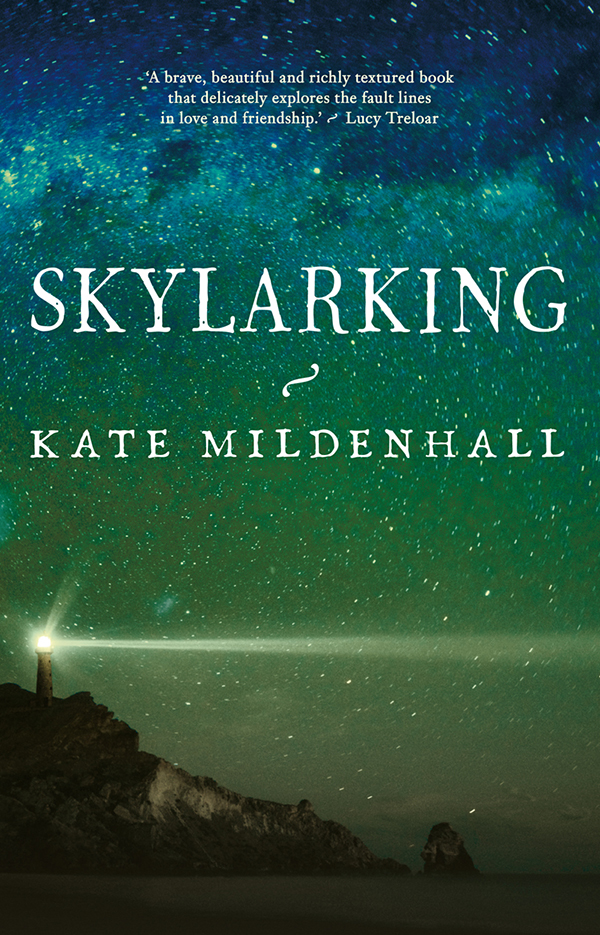

Skylarking

Authors: Kate Mildenhall

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

Copyright © Kate Mildenhall 2016

Kate Mildenhall asserts her right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Mildenhall, Kate, author.

Skylarking / Kate Mildenhall.

9781863958301 (paperback)

9781925435160 (ebook)

Romance fiction, Australian.

FriendshipâFiction.

A823.4

Cover design by Peter Long

Text design and typesetting by Tristan Main

Kate Mildenhall

is a writer and education project officer who currently works at the State Library of Victoria. As a teacher, she has worked in schools and at RMIT University, and she has volunteered with Teachers Across Borders, delivering professional development to Khmer teachers in Cambodia. She lives with her husband and two young daughters in Hurstbridge, Victoria.

To Gracie and Etta, may you know friendship, as I have, in all its ferocity and wonder

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

T

HE SKY WAS CLEAR AND BLUE FOREVER THAT DAY

. Clear and blue and so bright. Sunlight fell through the leaves, forming dark shadows and spots so blindingly white they forced me to look away. Harriet had packed a picnic: some ginger cake, half a loaf of soda bread, a square of butter wrapped in waxed paper. It seemed the beginning of something, this day â the sun, our being together again, making our way down the track to McPhail's hut.

I remember our chatter. I remember her grip on my wrist. I remember her veering from the track, pointing towards the hut, the absence of smoke from the chimney. I remember the empty echo of our knocks on the door. I remember letting ourselves in. I remember the hat, and the voice I used, strange and deep, that I pulled from somewhere inside me to make her laugh. Always, always, to make her laugh.

I remember the way Harriet turned, breathless, laughing, a strand of her golden hair caught on her bottom lip.

After that, I try not to remember.

ONE

T

HEY CHOSE A GOOD SPOT FOR OUR LIGHTHOUSE

. H

IGH

on the layered stone of a cliff face that jutted out, decisively, into the ocean; it was the kind of location that seemed confident, arrogant enough for a lighthouse. The dusty scrub of the headland stood hardly as high as the height of a man. While the sky was often endless and vivid, as soon as you left the grassy green slope of the lighthouse paddock, you could feel trapped and airless in the twiggy underbrush of the ti-tree and the thick canopy that blocked out the sky and muffled the sound of the waves. From the edge of the cliff, or as close to the edge as I had ever dared to go, there was only ocean and ocean and ocean, stretched out in the silky blue of a lady's skirt, all the way to the horizon.

I was nine, Harriet eleven, when we first clambered out over the stone wall to stand on the farthest point. It was one of those days where the sun glare made my eyes ache, and the sky was clear in a great arc, but the wind off the sea whipped any heat out of the day and forced watery tears down my cheeks. We had already taken our turn at dragging the bedding into the laundry in great piles and heaving the sodden mass out again to be thrashed dry by the nor'westerly. Now we were free.

We knew the rules about the wall and the cliffs, and the warnings we'd been told since we were small about how easily we could tumble over the cliff's edge and be dashed upon the rocks below, or swallowed up by the waves or, worse still, gnashed in the jaws of a great white shark. As a child, the threat of what lay beyond that wall was enough for me. Sitting in the latrine that had been built high out on a ledge over the sea, I could look down between my legs and see the foaming white froth spill over the rocks far beneath me. I would swallow hard and feel a roar in my ears until I could fix my gaze upon the swinging wooden door.

So I had kept away from the cliff. But now Harriet and I thought we were the oldest and wisest young ladies of the colony. What Harriet had in her two years of seniority to me, I made up for in bravery and cheek. You couldn't have picked it then; it was only later, when it was obvious Harriet was becoming a young woman and I was yet to outgrow my childhood body, that you'd have said she was clearly the eldest.

âBet you'll never go beyond the wall,' I said to Harriet as we lay on the grass.

âProbably not.' Harriet was a lazy type of beautiful, sweet and curly and far too used to being mollycoddled by her mother. She didn't see the point in doing anything outlandish; she didn't feel the fire as I had begun to. At least, she didn't feel it then.

âI would do it.'

âNo, you wouldn't, you just say that. You've a big mouth, Kate Gilbert, but you're not as brave as you think.'

A blush burned up my cheeks. I hated that I was laid bare before her.

âI'll tell you what the view is like when I get back.' I scrambled up and stomped towards the lighthouse and the stone wall that lay beyond.

âKate, I didn't mean it. Please don't. Your mother will be livid.'

âI don't care,' I called over my shoulder into the wind.

I knew she would chase after me â she always did. By the time I was at the low rock wall, she was beside me, breathing hard.

âCome on, Harriet! I won't fall if you hold my hand,' I said as I stepped over.

She glared at me but hooked her leg over the low wall and followed me through the prickly heath towards the edge. Only that few feet closer to the sea, and the sound was magnified, a crashing thud that echoed up through the solid rock and vibrated in my body and my ears. I was consumed by it. It was as though a single thread had been plucked from my dress and stretched all the way to the cottage where Mother would be bustling about in the kitchen. It held me, but it was thin, and it blew out in an arc like a spider's silk in the wind. I reached for Harriet's hand and told her where to place her black boots as we inched forwards in the shifting stones.

I was a lighthouse girl and I had stood on the edge of cliffs before, but not this one, and never so high up. Harriet stopped and let go of my hand as we got closer, spooked by the buffeting wind and the sudden space that was opening up before us where the edge of the rock dropped into nothingness.

âKate, this is far enough. We've seen it; we've gone further out than the boys. It could crumble away.' Harriet was frozen, white hands gripping a salt bush that would do nothing to hold her if she slipped.

âI want to see over the edge,' I shouted, and my mouth filled with cold air as the sound was snatched away from me.

âWell, I'm not going any further. You'll get yourself killed!'

I turned. âCome with me, Harriet, just a little bit further. I won't let you fall.'

Her face was white and creased with worry. Some part of me, deep inside, grew stronger when Harriet was scared. I needed her beside me, to feel her trembling hand in mine, to have the courage to get to the edge myself. I took her hand.

âWe'll go slowly; you tell me if you need to stop. Just to that rock there. We'll be able to see the whole world.' Her face did not shift, but she began to move her feet. Together we crept forwards, bodies braced against the wind, the sea glittering in front of us and all around.

âKate â¦' Harriet warned me, and I knew it was close enough.

Below us the rocks looked as if they had crumbled into the sea. To the right there was a river of brown and green glinting in the sunlight, broken glass where the men tipped our rubbish over the edge. Out beyond the swirls of white water and dark shadows of submerged rock, birds circled and then plunged into the water, leaving small splashes in their wake. The silvery glint of a school of fish flashed under the surface of the water. The sound of the wind out there was a high whistle in my ears, and I clapped my other hand up to stop the cold prick of it worming into my brain.

âOh,' breathed Harriet, her face close to my ear.

I turned to see her eyes bright with the light and the water and the brilliance of it all.

This was surely joy. And terror â for I was seized by the thought, so clear, that I could step forwards and then be falling, weightless. And more than that: Harriet's trust was so warm and damp in the grip of my hand; I could take her with me. We could be like sisters forever, leaping out into the air. Perhaps we would find that we could fly, and we would circle up and up, calling to each other, laughing at the wonder of it, looking down at the lighthouse, the cottages, the slope of green speckled with goats, the little paths etched through the scrub, the shapes of the children playing, as we circled ever higher, unbound by the earth.

I stepped back suddenly, pulling Harriet with me, and sat down with a thud.

âKate! You scared me!' Harriet crouched down next to me. âYou're as white as a ghost.'

âI was dizzy, that's all.' My head spun, and the sun was dazzling.

âCome on,' she said and heaved me up and back towards the solid bulk of the lighthouse, the settlement, all our earthly goods.

I still see it sometimes, in my dreams, my mind's eye. I see it but not quite as it was, and I wonder what other imaginings I have mixed up with the truth of the past. The two of us, arms outstretched to the sky, the sea, fingertips touching, and the wind rushing through us, our hair, our skirts, our breathless laughter as we stood on the edge of terror and wonder and marvelled at how brave we were.

TWO

I

DON

'

T REMEMBER LIFE BEFORE

H

ARRIET

.

History will tell that there was a point in time when I was just Kate, and Harriet just Harriet. But everyone on the cape understands that from the day she arrived we became Kate and Harriet. Harriet and Kate. One did not fully exist without the other. The story goes that we ran towards each other, Harriet some weeks past her fifth birthday and me just shy of my third, and clapped hands in delight at the sight of the other. From then on we shared everything. Games and dolls and secrets and adventures and, once we grew older, the chores and then school that filled our mornings before we were released to run wild upon our cape. Not sisters, but we might as well have been. At some point I realised that it was mere chance that Harriet and I had been put on this earth at the same time, on the same stretch of land. It made me fearful. For if God held such power, the power to make me so infinitely complete, could he not also hold the power to make me the opposite?

Harriet loved me like a sister because she had no siblings. Only later would I truly know what it must have been like for Mrs Walker, Harriet's mother, to have lost her second child before its time and then to lose that very bit of her that could ever bear a child again. I, on the other hand, soon had a sister, Emmaline, four years my junior whom Harriet and I delighted in cuddling, but whom we grew tired of once she reached the age where she could talk. I tried to get our brothers to play with her instead â James, who was one year older than Emmaline, and William, who arrived two years after her; but the boys stuck together, as they do, and Emmaline was always somewhat on the outer. I felt guilty for it sometimes. But not enough to let her in. After Harriet, my brother George had been my favourite but he had gone and died of pleurisy and left me eldest. At nine, I still found it hard to decide if I was angry at him for this fact or only sad.

I was dark, and Harriet was fair. I, loud; she, prim. Harriet of the golden curls. Harriet, who seemed to absorb light and burnish it and throw it back out through her hair and her skin and her eyes so that to be in her presence was to be bathed in it. When visitors came to the cape they would gasp and put their hands out to touch Harriet, as though it were incredible to find such a glowing, radiant being on this ragged bit of coast. She collected ribbons, and I coveted books.

I remember the day my most-treasured book arrived aboard the supply boat by way of a parcel from Harriet's aunt. Harriet and I were bursting with anticipation when we saw the post amongst the supplies waiting to be delivered and ferried up the track to the station. The supply boat only got to us every two months so there were always plenty of packages and sacks and boxes to be unloaded. After we had run back and forth distributing tea here and sugar there and fresh meat and butter, and the store cupboards of each of the cottages were again stocked with goods, Harriet and I raced to her room with the parcel and shut the door.

We sat atop Harriet's bed with our legs crossed, the package between us. It was heavy and rectangular, wrapped tightly in brown paper and tied with string. Sometimes her aunt would include a satin ribbon, or a tin of sweet biscuits, once four tubes of paint â red, blue, yellow and white â and a beautiful wooden brush. My fingers itched to rip at the paper and have the contents revealed in all their glory, but Harriet preferred to go slowly, savour the moment, and it was, after all, addressed to her. Harriet unknotted the string while I wriggled impatiently.

âGo on, then. You do the paper,' she said and passed the package to me.

I was careful not to tear it; we would use every inch of that paper for drawing and painting later. Finally the contents lay before us. Two magazines, a pair of red woollen socks, a small book of nursery rhymes and a larger parcel, with a message in cursive on a card fixed to the top.

On the occasion of your twelfth birthday, dear Harriet. May you derive your own valuable information, pleasure, great profit and unbounded amusement from these pages.

Harriet picked up the package and weighed it in her hands. âIt's another book,' she said, rolling her eyes.

Her aunt, Cecilia Butterworth, was both appalled and thrilled by the notion of her brother raising his only child on an outpost such as our cape. She saw it as her duty to take charge of Harriet's cultural education. She did not, of course, know that Harriet never read the books she was sent, for I begged Harriet not to say, and instead I devoured each one as it arrived, and then again, many times thereafter.

Harriet passed this smaller parcel to me and threw herself back on her pillow with one of the magazines.

I held it reverently in my hands and eased the wrapping back. A book thick with many pages and a soft leather cover in green with a title inlaid in the centre:

The Coral Island.

I must have had some inkling then of what those pages would give me, of what pictures and ideas would be imprinted on my mind forever more, for it was as though I could hear a whooshing sound, like that when Father lit the lamp, the sound right before it began to glow, getting louder and brighter as it went.

Poor Harriet lost me for a few days after that. She would appear on our verandah, her face wide open and ready for whatever adventure the day might present; I would only raise my head from the book, shake it and go back to the brilliant blue waters and soft breezes of the Pacific, and the adventures of Ralph and Jack and Peterkin.

I wondered at the preface to the book many times. The words impressed a certain pattern on my mind and the back of my tongue, and I felt them thudding softly there as my eyes flitted across the page.

â¦

If there is a boy or man who loves to be melancholy and morose, and who cannot enter with kindly sympathy into the regions of fun, let me seriously advise him to shut my book and put it away. It is not meant for him.

And by omission, not meant for me. For girls, or women, or any of our sex at all. Despite the closed door of this first page that tried to hold me back from the adventures within, I rushed on headfirst into a world of deserted beaches, and dark savages made good and kind by the lightness of God, the paradise of friendship and camaraderie in the face of adversity. Reading it made me feel as though I, too, were part of some grand tradition.

The only problem was, of course, that I wasn't going anywhere. Being the daughter of the head lighthouse keeper on a remote cape in a young colony was an adventure of sorts, I supposed. But I watched the ships sail by from the cliff top and knew that they would not stop for me.

On fine days, I sat out on the orange rock that was shaped like a steamed pudding and imagined how Harriet and I might sail off together. Even though the peppery scent of the scrub on that headland ran through my blood, I knew that there must be other places that would thrill me. And while I hoped that Harriet would be by my side as I adventured off into the great unknown, I knew this was unlikely. Where I had dreams of boats and pirates and coral island adventures, Harriet saw a future of a home and hearth filled with all the babies her mother had failed to have.

I never dreamed that it would be Harriet who left before I did.