Sisters in the Wilderness (43 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

Catharine's first priority, in the early 1860s, was to find a publisher for the manuscript on Canadian plant life she had rescued when Oaklands went up in flames. Her visit to Toronto in 1863 gave her the opportunity to hawk it round the publishing houses. Vincent Clementi, the Anglican minister at Lakefield, had sketched a few of the flowers mentioned in Catharine's manuscript. Armed with these scrappy efforts, and five dollars that the Reverend Mr. Clementi had lent her, Catharine laid siege at the door of the newly established Toronto branch of the Scottish publisher Thomas Nelson. But the door never opened. “My patience has not been rewarded,” she wrote to stay-at-home Kate, explaining that she

must return home before she ran out of money. She left the manuscript with friends in Toronto: “May be Mr. Nelson will write to me soon and some good may yet come to us through what as yet seems a fruitless expenditure of time and money.”

The following year, it seemed as though the manuscript might be published as “The Plants of Canada” by the Hamilton Horticultural Society, which was hosting the Provincial Agricultural Fair that year. But Catharine's hopes fell when she was told that the Society had decided it could go ahead only with the help of a government subsidy. She dismissed the president of the Horticultural Society as “a man not to be relied upon” and despaired of the colonial government ever having the imagination to put money into a comprehensive catalogue of Canadian plants. In the opinion of Sir William Hooker, she had been told, “Canada was behind every one of the British Colonies and all civilized nations in Scientific literary effort especially in Botany.” Strickland

amour-propre

came to the fore as Catharine emphatically concurred with the director of Kew Gardens: “I think the Great Man was rightâthere is certainly a want of encouragement in this country for literary talent.” But she was driven as much by financial as scientific imperative: “I am so anxious to earn what will pay our bills that I write even when I have no hope of a market.”

Catharine refused to be discouraged. She laboriously copied out her manuscript, then sent it off to all the people she could think of who might recognize the value of her work and give it a public endorsement. One copy landed on the desk of Professor John Dawson, a geologist who had become principal of McGill College in Montreal; another arrived at the doorstep of William Hincks, professor of natural history at the University of Toronto. Catharine also sent a copy to George Lawson, a Scot who had published more than fifty articles on botany before his thirtieth birthday, and who had arrived at Queen's College, Kingston, in 1858 to teach natural history. In 1860, he'd founded the Botanical Society of Canada, which was soon busy cataloguing Canadian plants and advising farmers on pest control.

In the end, it was none of these well-positioned or ambitious men who helped Catharine get her work in print, but her own niece, Susanna's daughter Agnes Fitzgibbon.

The older Agnes Moodie Fitzgibbon got, the more she resembled her mother. She had Susanna's delicacy of appearance and air of vulnerability that hid an iron will. She shared her mother's sense of humour, wicked temper and stylish dress sense: her bonnets reflected Parisian modes, and her skirts were always as wide as fashion dictated. Sharp-featured and proud, with a penetrating gaze, Agnes was extremely beautiful. Since her marriage in 1850, Agnes had lived in Toronto, and, now in her twenties, she far preferred the diversions of a big city to those of rural life. She found Toronto at mid-century just as thrilling as Susanna had found London in the 1820s. And Toronto

was

exciting as it swelled from a muddy little port to a booming railroad city. Men were making fortunes in the milling, transportation and banking industries, and building monuments to their success in the form of splendid stone banks and office buildings.

Unfortunately, Charles Fitzgibbon was not one of the Toronto entrepreneurs making his fortune. He and his wife had little time and less money to enjoy many of the new civic amenitiesâthe library and music hall of the Mechanics' Institute on the corner of Adelaide and Church, built in 1854, or the splendid row of new glass-fronted stores on King Street, offering clothing, dry goods, carpets, curtains, books and boots. Agnes spent the fifteen years of her marriage to Charles Fitzgibbon in the usual Victorian cycle of repeated pregnancies, births and intermittent deaths. Four of the eight children born to Agnes and Charles died before they were ten years old. She had some help from a succession of teenage Irish girls (the only domestic servants that the Fitzgibbons could afford), but she could rarely leave home. There were few opportunities for strolling down King Street's plank sidewalks, or watching games of cricket at the Old Garrison Reserve during the summer, or ice-boating in the harbour in winter. Most of her excursions were walks in the nearby valley of the Humber River, where the children played on the

riverbank and she sketched wildflowers. Her mother had taught Agnes how to paint flower pictures when she was a little girl, and Agnes's skill had quickly surpassed Susanna's.

Catharine had always had a close relationship with Agnes; aunt and niece got on much better than mother and daughter. Agnes “was always my own dear child when she was a baby,” Catharine confided to her sister Sarah in England. “I always had her with me when dear Susanna was ill or confined, and she has been like one of my very own daughters all her life and very dear to me she is.” It suited Catharine that Agnes Fitzgibbon lived in Toronto, which was starting to rival Montreal as a centre for Canadian publishing. The Fitzgibbon house on Dundas Street had quickly become her base on her occasional trips to Toronto to hustle publishers, and Catharine would moan to Agnes about their reluctance to take on her manuscript unless she could produce better illustrations.

In 1865, Charles Fitzgibbon died, and thirty-two-year-old Agnes was abruptly widowed, with a family to support. “Having only the proceeds of my husband's life insurance upon which to feed, clothe and educate them, it was necessary for me to replenish my purse before its contents were exhausted,” she later wrote. But her only salable skill was her dexterity with a paintbrush. She decided to put together a volume of flower illustrations, with text provided by Catharine from her lengthy manuscript.

It was a wildly ambitious project. Agnes's mother and aunt could have thrown cold water on any hope that such a book would make much money. But when Agnes set her mind to somethingâwhether it was marriage when she was only seventeen, or authorship when she had no experience in the book tradeâshe usually achieved it. Agnes displayed the same Strickland drive that had kept both her mother and her aunt scribbling during their wretched years in the backwoods. She certainly cut a more impressive figure in publishers' offices than her aunt, whose country-mouse clothes and eagerness to distribute gingerbread recipes were out of place amongst Toronto's new entrepreneurial elite.

Agnes began by approaching John Lovell, her mother's publisher in

Montreal, to buy the idea of an illustrated volume of Canadian wildflowers. Lovell was a great champion of the need for a vibrant Canadian publishing industry, and he liked Agnes's determination that her book should be an exclusively Canadian production. He agreed to be the publisher. Next, Agnes co-ordinated efforts to sign up five hundred subscribers for the proposed volume. At five dollars a volume, it was an expensive proposition, but Agnes bullied all her family, friends and acquaintances into agreeing to buy the book before it was even in print. Then she sketched out the ten illustrations required for Catharine's text and looked around for a printer who could reproduce them by means of the newly developed process of lithography.

Lithography, perfected by the Munich printer Aloysius Senefelder in 1796, was a popular medium amongst nineteenth-century artists such as Goya and Daumier. By Agnes's time, it was well-known in the United States through the colourful scenes of horses, yachts and newsworthy events published by Currier and Ives. But it had only reached Upper Canada in the 1830s, and was used there exclusively for maps, charts, cheques and banknotes. The colony's artists considered the quality of local lithography far too poor for illustrations; Cornelius Krieghoff 's

Scenes in Canada

were sent back to Munich to be lithographed. Agnes did enough research to convince herself that it was the perfect medium for her drawings because hundreds of illustrations could be taken from one stone. However, no Toronto printer could undertake the production of such sophisticated designs, so she decided that “if no one else could, I must endeavour to do it myself.”

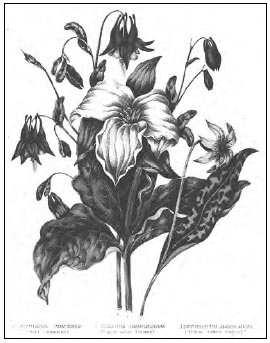

She acquired a specially prepared block of limestone from a printer called Ellis and drew a trillium on it. Under Ellis's guidance, she etched around the lines with chemicals, then greased the plate, rolled ink over the design, and pressed a damp sheet of paper onto the stone. A perfect reproduction of the trillium appeared on the paper. Fired up by success, Agnes drew the first of her own exquisite floral designs onto the stone and printed out five hundred plates. Then she cleaned off the first design and repeated the operation with the second design for five hundred

copies. She worked on methodically, reusing the same stone each time, until she had five hundred copies of each of her ten designs.

Both Agnes's aunt and her mother were in awe of Agnes's achievement. Catharine recognized that this was “a gigantic effort to be executed by one person”âespecially when the person was a single parent with a limited budget. Susanna, ever the pessimist, felt that her daughter had taken on far too much. She wrote to Catharine that if Agnes tried to paint all the plates herself, “it will well nigh kill her ⦠I much fear either of you embarking in such a hazardous enterprise which if it did not succeed would be utter ruin.” But Agnes ignored the Cassandra chorus. She and her three eldest daughtersâMaime (then sixteen), Cherrie (thirteen) and Alice (ten)âsat down at the dining-room table of their house on Dundas Street and coloured the whole edition of five thousand illustrations by hand. Some of the illustrations featured a single plant, such as

Sarracenia purpurea,

or purple pitcher plant. Others showed an unrelated group of three or four flowers, such as

Veronica americana

(American brooklime or speedwell),

Rubus odoratus

(purple-flowering raspberry),

Moneses unifloea

(one-flowered pyrola) and

Pyrola elliptica

(shin leaf). Had the book been published in England, with a professional lithographer and artist preparing the illustrations, she later discovered, the cost would have been 1,500 pounds ($7,500).

It did not take Catharine long to assemble from her plant life manuscript the brief literary descriptions to accompany Agnes's lithographs. Each mini-essay (thirty-one altogether) was vintage Traill, combining a detailed description of the plant, its medicinal qualities, references to previous botanists' writings about it, a smattering of poetry and Catharine's personal opinion of its merits. She included the English, scientific and native names for each plant. And some of the information has a modern ring: for example, she described the medicinal qualities of coneflower, commonly known today by its Latin name, Echinacea. She mentioned that wintergreen could cure rheumatism, balsam made a good dye, and Indian herbalists used turnips as a remedy for colic. Of the species

Pyrolae

(wintergreen), she wrote an admiring description that is a botanic variation of something Agnes Strickland might have said about a particularly good-looking branch of the British aristocracy: “Every member of this interesting family is worthy of special notice. Elegant in form and colouring, they add to their many attractions the merit of being almost the first green thing to refresh the eye, long wearied by gazing on the dazzling snow for many consecutive months of winter.”

Frontispiece for “a most valuable addition to the literature of Canada,” to which citizens of the newly-minted Dominion eagerly subscribed.

Agnes Moodie Fitzgibbon's lithograph of a trillium: she and her daughters hand-coloured 5,000 illustrations.