Sisters in the Wilderness (20 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

Susanna, like Catharine, was a resourceful, practical woman. She was a better cook than her sister, and just as accomplished at preserving cabbage, pickling cucumbers, smoking bacon and plucking wildfowl. When presented with dead squirrels, she could transform them into pies, stews or roasts without a twitch of distaste. When they could no longer afford tea or coffee, she recalled a recipe for dandelion-root coffee in the

Albion

and promptly went out to dig up some roots. “The coffee proved excellent”; a supply was sent over to the Traills. But things went from bad to worse, and during the bitterly severe winter of 1836, Susanna's children were weak with hunger. Overcoming her kneejerk English sentimentality about pet animals, Susanna slaughtered her daughter Katie's pet pig, Spot. She noted with remorse, however, that while her family fell on the pork, their dog Hector, who had been Spot's boon companion, could not bring himself even to gnaw on one of Spot's bones.

Susanna and Catharine clung to each other in hardship. When the Traills were afflicted with “the ague,” as settlers always called malaria, Catharine noted that, “but for the prompt assistance of ⦠Susanna, I know not what would have become of us in our sore trouble.” In return, Catharine sent over bread and maple cakes for the Moodie family. Kitchen utensils and farming implements were shuttled between the two log houses.

Relations between the two brothers-in-law were less amicable. They were such different characters that, when things were going badly, it was almost inevitable that Thomas's lugubrious pessimism would irritate easygoing John, while John's consistently bad judgment about business matters would exasperate Thomas. Thomas was annoyed when the Moodies borrowed, and broke, the Traills' sugar kettle (although they had it mended for him). For some time, there was a distinct chill between the two men. This pained their wives, who knew their kinship was too valuable to disrupt with petty squabbles. Eventually, Thomas apologized to his brother-in-law: “I again express my sincere and bitter regret at ever having given you any uneasiness, the more particularly at a time when you had more than enough to annoy you otherwise. I hope we shall hence forward live as friends and brothers.”

As the decade drew on and harvests failed, in damp little log cabins scattered through the bush, settlers were starving. Those from genteel backgrounds, like the Moodies and Traills, were the most vulnerable: unlike working-class immigrants, they didn't have the manual skills to

farm for themselves, and they no longer had any money to pay others to work in the fields. Despair drove many to drink. News of the most hopeless cases travelled quickly from settlement to settlement.

Susanna heard about one half-pay officer in nearby Dummer Township, an epauletted and decorated veteran of military service in India, who was so depressed by the dreary cycle of isolation, poverty and crop failures that “the fatal whiskey-bottle became his refuge from gloomy thoughts.” Captain Frederick Lloyd finally deserted his wife Ella altogether and headed south. Susanna organized an expedition to take bread, gingerbread, sugar, tea and home-cured ham to the abandoned wife and her seven children. Since John was away, she asked Thomas, her brother-in-law, to accompany them. Thomas, Susanna and her friend Emilia Shairp, whose cabin was close to the Moodies', walked for miles in the bitter January cold through the “tangled maze of closely-interwoven cedars, fallen trees and loose-scattered masses of rock.” When they finally arrived at their destination, Susanna saw a picture of utter desolationâa woman struggling to maintain her dignity while watching her children shiver and weep with hunger. They had exhausted their supply of potatoes, which was all they had eaten for weeks. Susanna stared at the wan, emaciated figure in a thin muslin gown (“the most inappropriate garment for the rigours of the season, but ⦠the only decent one that she retained”). She looked at two little boys cowering under the coverings of a crudely made bed in the corner “to conceal their wants from the eyes of the stranger.” She stuttered out a formal greeting: “I hoped that, as I was the wife of an officer, and, like her, a resident in the bush, and well-acquainted with its trials and privations, she would look upon me as a friend.” The little family fell on the sackload of supplies with gratitude. As Susanna watched, she must have wondered whether this was what the future held for her.

Chapter 9

A Call to Arms

I

n early December 1837, Sam Strickland was too intent on keeping the heavy iron plough steady to notice the young lad racing over the hill towards him, waving a piece of paper. As dusk settled on the grey landscape, snowflakes began to swirl around the horns of the lumbering oxen. Sam urged Buck and Bright forward. He was late planting, and he knew that once he had finished his own field, he would have to help at his sister Susanna's farm. John Moodie had broken his foot while sowing his winter wheat and was limping around on homemade crutches.

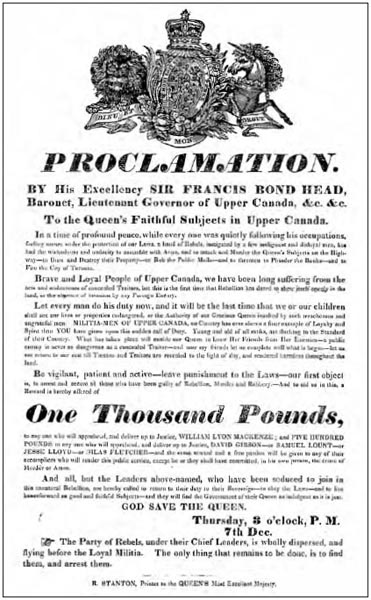

The excited cries of James Caddy, his neighbour's son, finally caught Sam's attention, and he grabbed the paper from the panting youth. It was a proclamation dated December 5, two days earlier, from the Lieutenant-Governor of the province, Sir Francis Bond Head. Rebellion had broken out in the colony. The Lieutenant-Governor called upon the loyal militia of Upper Canada to assist in putting down an armed uprising. Toronto

was under siege, James blurted out between gasps for air. William Lyon Mackenzie was at the head of a ragtag army of rebels. Shod in clogs and armed with rifles, pikes and pitchforks, they were marching down Yonge Street. Little Mac was challenging the rule of law, the authority of the British crown and the power of the Westminster-appointed governor. There was even talk, young Caddy breathlessly added, that Toronto had already been burned to the ground, Bond Head killed and war declared between Upper Canadians and the Yankees.

This was shocking news. Douro Township's gentlemen immigrants were too distant from Toronto to know that Bond Head was an arrogant fool who had misjudged the strength of popular feeling and had helped provoke the uprising by treating Mackenzie as nothing more than a raving madman. At the various harvest festivals and Strickland family celebrations along Lake Katchewanooka that fall, Little Mac had been regarded as a bit of a joke. “Mackenzie's treason,” in Catharine's words, “had been like the annoying buzz of a mosquito ever in the public ears.”

Now Mackenzie had co-ordinated his offensive with an uprising of the Patriotes in Lower Canada, led by Louis-Joseph Papineau, who were also demanding more control over the colonial government. Taking advantage of Bond Head's ill-advised decision to send his troops to Montreal, to quell the Patriotes there, Little Mac had launched an attack on a defenceless Toronto.

Within hours, eager to support the Crown, Sam Strickland had said goodbye to his family and set off through the December night to Peterborough, to join the Peterborough Volunteers. By the following morning, Thomas Traill was marching alongside Sam down the rutted cart-track towards Port Hope. A day later, John Moodie had shouldered his knapsack and limped on his crutches the eleven miles to Peter-borough, where he borrowed a horse and rode on to Port Hope at the head of two hundred more loyal volunteers. For Thomas and John, the call to arms was thrilling. Soldiering was their business. Soldiering meant the jangle of harness, the bark of orders, the acknowledgment of their officer statusâas well as regular meals and jovial male companionship.

It meant an escape, albeit temporary, from the backwoods and suffocating poverty. Both men dearly loved their wives, but the opportunity to defend the interests of the motherland was irresistible. It had an extra piquancy in 1837, because Britain had a new monarch, Victoria. For the first time in their lives, the rallying cry for these soldiers was “God save the Queen!”

For Catharine Parr Traill and Susanna Moodie, however, the news was appalling. Dutiful feelings of loyalty to British interests were swept aside by dismay at the prospect of their husbands' prolonged absence. They had infants to nurse and children to feed, and now they would also have to do the men's work in the dead of winterâkeeping fires lit, woodpiles filled, animals fed and paths cleared. The snowstorm had continued all night; weeks of freezing temperatures and snowdrifts lay ahead. “God preserve us from the fearful consequences of a civil warfare,” Catharine confided to her journal. “O, my God, the Father of all mercies, grant that he may return in safety to those dear babes and their anxious mother.” The backwoods reverberated with rumours: Toronto was beseiged by sixty thousand men; four hundred Indians had attacked the city and slaughtered all the inhabitants; American soldiers were crossing the border in support of Mackenzie. The two women were terrified that armed rebels might burst out of the forest at any moment, intent on rape, pillage and murder. “Became so restless and impatient I felt in a perfect fever,” Catharine wrote in her journal. Susanna and her children moved into the Traills' cabin.

In fact, the rebellion fizzled out almost before it began. There were scarcely any casualties, and William Lyon Mackenzie was forced to flee across the border. Bond Head offered a reward of one thousand pounds for his capture. When news reached the little settlement north of Peterborough that the men would soon be home, Catharine escorted Susanna home in the horse-drawn sleigh. With the children swathed in buffalo rugs, the two women wrapped themselves up in a blanket together and started laughing hysterically in the cold night air. Suffused with relief that their husbands were safe, they were overcome with the humour, as Catharine noted in her journal, of finding themselves “not a whit less happy than if we had been rolling along in a carriage with a splendid pair of bays instead of slowly creeping along at a funereal pace in the rudest of all vehicles with the most ungraceful and uncouth of all steeds.” Thomas and John were back on their farms only days after they had left.

Despite its comic-opera aspect, the rebellion had stirred everybody up. Susanna wrote an anthem calling on the “Freemen of Canada” to fight the “base insurgents.” Fifty years before Rudyard Kipling, she tapped into the British appetite for triumphant patriotism. It was soon on the lips of every soldier in Bond Head's ragged defence force. The second of its five verses made it plain that the loyalty of true Canadians, wherever they were born, must lie with the motherland:

What though your bones may never lie

Beneath dear Albion's hallow'd sod,

Spurn the base wretch who dare defy,

In arms, his country and his God!

Whose callous bosom cannot feel

That he who acts a traitor's part,

Remorselessly uplifts the steel

To plunge it in a parent's heart.

The rousing words were accompanied by banging pot lids and waving fists as Susanna's children marched around the kitchen reciting the anthem, while their father accompanied them on his flute.

The triumphant suppression of the '37 Uprising infused the Christ

mas celebrations two weeks later with additional jubilation. Catharine decorated her cabin with even more ingenuity than usual, threading dried cranberries onto pine boughs to simulate the red holly berries she had gathered as a girl in Suffolk. Her daughter Katie made a hemlock wreath and twisted her precious coral beads (which her mother had refused to sell) around the boughs. Catharine scrounged supplies from her brother

Sam to ensure a feast, and by the time the Moodie family arrived in their sleigh, the Traills' table was laden with the weight of roast duck, potatoes, vegetables carefully preserved four months earlier, pies, preserves and breads. While Thomas and John toasted the new Queen in treacle beer (made from treacle, hops, bran and water), Catharine distributed maple sugar sweets to the children.

After dinner, the two families went outside to play in the newly fallen snow. Both men were now limping, since awkward Thomas had fallen off his mount and sprained his ankle at a meeting of the militia in Peterborough a few days earlier. Though the men were unable to pull the children on their homemade sleds along the snowy paths through the woods, the two Strickland sisters, as usual, compensated for their husbands' handicaps.

It was only when night fell, and the women sat beside the Franklin stove nursing their infants and reminiscing about Reydon Christmases, that a sadder note crept in. They recalled jubilant wassailing parties while their father was still alive, when the Hall was thronged with merrymaking neighbours and attentive servants. They thought of their four older sisters in England. They remembered how, after their father's death, Agnes always took charge of celebrations, while gentle Sarah quietly produced a delicious dinner despite their straitened circumstances. “Our Christmas meetings at best are but a melancholy imitation of those social hours,” sighed Catharine. “Their chief charm arises here from the retrospect of the past and from the long train of affectionate remembrances that crowd thick and fast upon each other.”