Sisters in the Wilderness (23 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

Susanna swallowed her doubts and began to organize the move. There was a lot to do, but as usual she systematically and efficiently accomplished the task. She sold their stock, implements and household furniture, disposed of the livestock and made the necessary arrangements to lease the farm and leave the backwoods. Then she and the children sat back and waited for the onset of winter. There had to be a good base of packed snow on the corduroy roads before the two sleighs that John had hired in Belleville could make their way north to collect her. They waited and waited, and no flakes fell. On Christmas Day, her eldest son Dunbar looked out the window at the bright sunshine glittering on the ice of Lake Katchawanooka and groaned, “Winter never means to come this year! It will never snow again.”

It was six more days before a savage winter gale swept across the landscape. The following morning, Dunbar looked out at trees, lake and distant woods covered in a thick white mantle. The same afternoon, the

Belleville sleighs arrived (the storm had hit the lakefront a few days earlier). Blowing on their frozen hands, Susanna and Jenny quickly loaded their belongings. In the midst of all the confusion, Sam Strickland arrived and announced that he would transport his sister and her children to Belleville in his well-sprung lumber sleigh, which meant they would have a much more comfortable journey. Susanna always relaxed around her large, noisy, capable brother. Soon they were both laughing as they watched Katie try to squeeze the old cat Peppermint into a basket. Sister and brother were convulsed when Jenny appeared, balancing on her head no fewer than four hatsâa drawn silk bonnet, a calico cap, a beribboned straw sunhat and a grey beaver-fur hat. “For God's sake take all that tomfoolery from your head,” Sam instructed her between guffaws. “We shall be the laughing stock of every village we pass through.” Faithful Jenny had stuck with the Moodies through all their tribulations, but as Susanna prepared to reenter “civilization,” the social gulf suddenly yawned between mistress and servant. Susanna sent Jenny ahead on the uncomfortable hired sleigh.

A last wave of nostalgia washed over Susanna as she took a final look back. She saw the log cabin in which she had given birth to her three sons; she gazed at the snake fence she had constructed with her own hands around her garden, and at the lonely lake beyond. She realized that her Chippewa friends had silently materialized in the clearing: with tears running down her cheeks, she kissed the women and their babies in an affectionate farewell. Daylight was nearly gone, and Sam had no time for his sister's sentimentality. He hurried her onto the seat next to him, shot a quick glance backwards to make sure children, baskets and bags were safely stowed and gave a loud “Giddyup” to the horses.

Susanna was mute as the sleigh slid through the incredible pall of the winter landscape. Tears ran silently down her face as she listened to the jangle of the horses' bridles, the rhythmic

chunk-chunk-chunk

of their hooves, the slither of runners on hard-packed snow, the rustle of dried leaves still clinging to the trees. Cold air entered the travellers' nostrils like knives; the horses' heads were soon white with frost. The party

spent that night in Peterborough, where Susanna was able to arrange for the return of little Aggie to her own family after close to a year with Mary Hague.

In town, Susanna had a jarring insight into her children's ignorance of any life beyond their hardscrabble solitude in a backwoods cabin. As the loaded wagon entered the main street, five-year-old Dunbar stared in amazement at buildings that nestled up against each other. “Are the houses come to see one another?” he asked. “How did they all meet here?”

Chapter 10

Belligerent Belleville

B

y the admittedly modest standards of Upper Canada in 1840, Belleville was close to the acme of sophistication, with far more class and culture than Cobourg or Peterborough. It was large (the most important settlement between Kingston and Toronto) and well established (its Loyalist founders could trace their history in Upper Canada back three generations). It had been named after Lady Bella Gore, the beautiful young wife of Governor Francis Gore, in 1816, and its ladies prided themselves that their fashionable attire was less than a year behind London's.

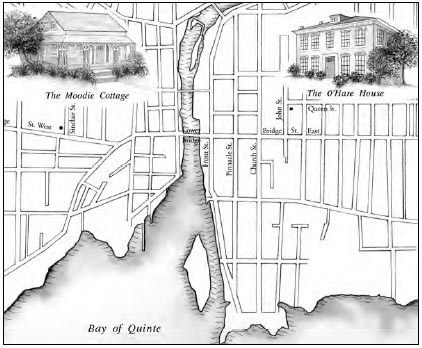

In 1840, Belleville was one of the most important towns in Upper Canada,

with a good harbour and a growing population.

Belleville's economy was thriving, thanks to two flour mills, two carding mills, four sawmills, three breweries, seven blacksmiths' shops and two tanneries. At its wharves, sailboats bringing goods from northern New York State via the Bay of Quinte jostled with fishing boats and steamers carrying passengers along the lakefront. Its twenty-six shops and twelve grocery stores carried imported goods from the United States, the West Indies and Europe, as well as locally grown produce. The town had at least one bookstore and a circulating library, and on Sundays, its 1,700 citizens had four churches to choose from: Presbyterian, Methodist, Roman Catholic and Anglican. While Belleville's finest families lived in solid limestone houses with large sash windows, the town still had no sidewalks, and pigs roamed freely along the muddy streets, gobbling up the garbage. But residents of Belleville were confident that they were in the vanguard of colonial progress: every seventh house had a streetlight in front of it, which was lit on moonless nights so that pedestrians could avoid the puddles and pigshit.

Underneath this urbane surface, however, seethed all the most vicious emotions of the raw young colony. Every kind of prejudice flourished in the town: Tories versus Reformers, Methodists versus Anglicans, Irish

versus Scots, Protestants versus Catholics. Belleville's numerous Irish Protestants had established one of the most active Orange Lodges in the province, and they commemorated the defeat of the Catholics in the 1690 Battle of the Boyne with bloodthirsty glee. All over Upper Canada, Orange Lodges were well on their way to becoming the most important club in every small townâboisterous, populist and passionately pro-British. But the Belleville Orange Lodge was particularly forceful.

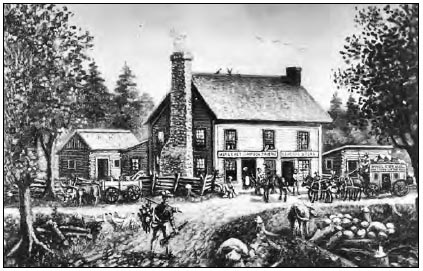

Mrs. Margaret Simpson's tavern, where the MontrealâToronto coaches

changed horses, buzzed with partisan gossip.

By the time John Dunbar Moodie had secured a permanent job in Belleville, he was well aware that the town pulsed with bad blood. As he strode down Front Street in his military uniform, he endured the catcalls of those who had supported the rebels in '37. In Mrs. Margaret Simpson's smoky tavern on the waterfront, he heard the Scots immigrants sneer at the “Paddies” and watched the Irish immigrants come to blows with the “damn Yankees.” He was at the opening of Belleville's most imposing new buildingâthe county jailâwhich immediately filled up with drunks, debtors, cheats, violent criminals and thieves. The level of partisan sniping and name-calling was enough to discourage even an

optimist like John. “I sometimes wish I could clear out from this unhappy distracted country where I see nothing but ultra selfish Toryism or Revolutionary Radicalism,” he wrote in 1839. “The people in this part of the country are split into some three or four factionsâThe Catholics harbouring dark designs under an hypocritical profession of loyalty and Orangemen goading them on to rebellion by claiming all the loyalty in the country to themselvesâwhile the native Canadians [second- and third-generation immigrant families] are hugging the loaves and fishes as their own peculiar perquisite, agreeing with the others on hardly any one point but in hatred of the Scotch and their Church.”

In the early days of 1840, however, John was too eager to see Susanna and their five children to dwell on Belleville's shortcomings. He had a new job and a new house, and he was going to make a new start in the new decade! He strutted past the unpainted frame houses that sprawled untidily along Bridge Street and Front Street, the two main streets that intersected on the banks of the Moira River, carefully avoiding the potholes and happily greeting passers-by. He was good at remembering names, and he delighted in offering cheery hellos to every lawyer, merchant, housewife and child he bumped into. Short and plump, his vest straining across his belly and his ready smile almost obscured by his mutton-chop whiskers, he radiated geniality. At last, after two years of almost constant separation, he could dream about cosy evenings with his family grouped around the fireside in the pretty, neat little cottage he had rented and furnished. He could imagine Susanna's relief that she no longer had to struggle out in the chill of a January morning to milk the cows; instead, she could purchase staples at a store. He could almost hear little Agnes and Katie singing nursery rhymes as he accompanied them on his flute. He smiled as he imagined his three sons chasing chickens in their yard. Most of all, John longed to show Susanna the china tea service he had recently purchased. There could be no more satisfactory symbol of Susanna's release from the backwoods, he fervently believed, than the chance to return to the old Reydon Hall custom of taking tea at four o'clock each afternoon in bone china cups.

On the third day of January, Susanna, Jenny and the children arrived in Belleville after a long and freezing journey from Peterborough through Cobourg. Thin-lipped with cold, Susanna was tearful and nauseated, and in no mood to be cheered up by bone china. Her first bit of news for John, as she pressed little Johnnie, now fifteen months, into her husband's arms, was that she was once again expecting a baby. John had made a brief visit home the previous Novemberâjust long enough to conceive their sixth child.

Although Susanna didn't welcome another pregnancy, both she and John were proud of their rapidly expanding family. Had she wanted to, Susanna could undoubtedly have learned about natural abortificeants (her Indian friends might have told her about the effectiveness of oil of cedar, hellebore or ergot of rye). But birth control and terminations were rarely considered by Canadians of this period. A brood of eight or ten children provided a ready supply of much-needed cheap labour for the farm, even if it did put a huge strain on the mother's health. Even in larger towns like Belleville, the birth rate remained high until the late nineteenth century, because children were still regarded as insurance for the future. One of the ditties popular in the colony suggested that:

Of all the crops a man can raise

Or stock that he employs,

None yields such profit and such praise

As a crop of Girls and Boys.

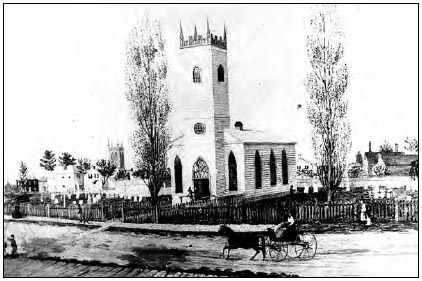

The following day, Susanna set off to explore Belleville. She was deeply disappointed, and irritated by what she perceived as its pretensions. She had hoped for a thriving market town like Bungay or Southwold, with cobbled streets and charming stone cottages. Instead she found “an insignificant, dirty-looking place” in which the frame houses were “put up in the most unartistic and irregular fashion.” Large sections of Front Street remained unpaved, and the slabs of limestone on the paved sections were laid so carelessly that pedestrians were constantly tripping and falling. Susanna harrumphed that the “paving committee had been composed of shoe-makers,” because so many shoes got destroyed in falls or stuck in the deep, mud-filled potholes. Her relief at the prospect of regular Sunday worship was diluted by her disgust at the brick-and-frame “eyesore” that was St. Thomas's Anglican Church. St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church, on the same block, was an even shabbier wooden building. John's assurance that at least five households boasted pianos did not raise her spirits. Only the cedar-fringed banks and “rapid, sparkling” water of the Moira River, which thousands of logs floated down each spring, brought a smile to her face. The river reminded her of the Otonabee. Faced with the gossipy little community of Belleville, Susanna grew quite nostalgic for the privacy of her cabin on Lake Katchewanooka.