Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon (5 page)

Read Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon Online

Authors: Stephan V. Beyer

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Religion & Spirituality, #Other Religions; Practices & Sacred Texts, #Tribal & Ethnic

The Attack by Don X

In the late iggos, dona Maria was employed from time to time to do healing

ceremonies for ayahuasca tourists at a lodge about two hours by boat from

Iquitos. There she worked alongside a well-known ayahuasquero whom we

will here call don X.

As we will discuss, accusations of sorcery are not infrequent in the Upper

Amazon, and can have serious consequences. Although I knew don X personally-indeed, I was living with him in his jungle tambo during part of this period-the constraints imposed by the relationship of confianza I had with dona

Maria and her friends prevented me from asking him for his side of the allegations against him. Hence his anonymity.

Now, don X had a son whom he had trained as an ayahuasquero, and who

was able to pick up occasional employment at the lodge when dona Maria was

unable to attend. According to dona Maria and her friends, don X decided that

if dona Maria could be eliminated, the way would be open for his son to take

her place in the relatively lucrative business of healing gringo tourists. So don

X attacked dona Maria with virotes, magic darts, sending them deep into her

chest and throat, causing her to suffer a serious stroke.

The attack took place at the tourist lodge, at night, when dona Maria was

sleeping. She tried to get out of bed to urinate, but, when she got up, she

fell to the floor, partially paralyzed, unable to move. She cried for help. One

worker came, but he was not strong enough to move her; eventually, with the

help of the gringo owner, she was lifted back onto the bed. "She was just like

deadweight," the owner later told me. "It was all I could do to get her up to

her bed myself."

Dona Maria spent the next six weeks in the hospital, slowly recovering

from her stroke. She had originally resisted hospitalization, because she believed that the injections she would be given there would kill her. She felt

herself to be lost. "Where will I find help?" she thought. Throughout this

period, she heard a wicked mocking brujo laugh-the voice, she realized, of

don X.

When she returned home, she was cared for by a Cocoma Indian shaman

named Luis Culquiton, who was able to remove a few of the virotes, and who

took care of her for six months. Don Roberto, her maestro ayahuasquero, had

gone away to his chacra, his swidden garden in his village, but sent her medicine from afar. Although she recovered slowly from her stroke, she was unable to drink ayahuasca. She was thus cut off from the very sources of her protection; indeed, part of the cleverness of the attack was to separate her from

her protectors by making it hard for her to drink ayahuasca.

The problem was that Maria continued to work with don X. She did not tell

anyone that she had recognized his mocking laugh. Don X, as brujos do, allegedly concealed his malevolence under the guise of concern and sympathy.

The virotes in her throat kept Maria from being able to sing at the healing

ceremonies. "See, she can't sing," said don X to the gringo owner. "She is still

too weak. You need to bring in my son."

Finally, after six months, don Roberto returned and sucked out the remaining virotes, but Maria continued to be weak. After her stroke, she said, her

brain was "blank," and all the power she had received from ayahuasca was

taken from her. She lost her visions, she could not drink ayahuasca-yet, she

said, her spiritual power remained, because that came from Jesucristo and

Hermana Virgen. "Whatever happens," she told me, "you must keep going

forward, never give up."

Slowly, she began to drink ayahuasca again. As she drank more and more,

she began to recover some of her powers. Yet, at the same time, she continued

to work with don X, who actively suppressed her ayahuasca visions with his

secret songs. Indeed, one of the ways a sorcerer attacks another shaman is

by using an icaro to darken the vision of the victim. I do not know why Maria

continued to work alongside her attacker-perhaps concern over accusing a

well-known ayahuasquero, although, over time, she let the identity of her attacker be known; perhaps bravado, a demonstration of her own fuerza; perhaps-and this seems to me most likely-a demonstration of the forbearance

she prized as part of her practice of pura blancura, the pure white path.

In July 2oo6, dona Maria died of complications resulting from the stroke.

She continued her healing work, especially with children, to the end.

Dona Maria often shook her head in dismay at my questions, my blockheaded inability to absorb the immense plant knowledge she offered to me. What I needed to learn I would learn, over time, from the plants themselves,

she said; the way for me to learn was to "continue on, and all will be shown

to you." This was typical dona Maria. When I would say I couldn't learn any

more, she would scold me. Study, study, study, she would tell me. Follow, follow,

follow.

PRELIMINARIES

It is getting dark, and the room is lit only by a few candles. People are beginning to gather. They talk quietly in small groups or lie in mute and solitary

suffering on the floor. People tell jokes and exchange stories; they talk about

their neighbors, about hunting conditions, about encounters with strange

beings in the jungle. Some of them will drink ayahuasca, and some will not;

some will drink for vision, and some for cleansing. Some drink in order to

see the face of the envious and resentful enemy who has made them ill, or the

one who has caused their business plans to fail, or the one with whom their

spouse is secretly sleeping. Some drink to find lost objects, or see distant relatives, or find the answer to a question. Some may use 1a medicina as a purgative, a way to cleanse themselves. All are here for don Roberto to heal them.

Except for me. I am here not to be healed but, rather, to learn the medicine.

I am here to be the student of el doctor, la planta maestro, la diosa, ayahuasca,

the teacher, the goddess; to take the plant into my body, to give myself over

to the teacher, to become the aprendiz of the plant, while under the powerful

protection of don Roberto's magical songs, his icaros. I have been following

la dieta, the diet-no salt, no sugar, no sex, eating only plantains and pescaditos, little fish. I have drunk ayahuasca with don Roberto before, and with other

mestizo healers around Iquitos-dona Maria, don Rbmulo, don Antonio. I

am nervous about the vomiting. I wonder what I will see tonight; I wonder if I

will see anything.

Don Roberto comes into the room and moves from person to person, joking, smiling, asking about mutual acquaintances, gathering information,

talking about matters of local interest, getting the stories of the sick. Some

people laugh at a joke, feel the brief light of his full attention on them and their problems. He spends some time talking informally with each person

who has come for healing, and often with accompanying family members,

quietly gathering information about the patient's problems, relationships,

and attitudes. In addition, as himself a member of the community, don Roberto often has a shrewd idea of the tensions, stresses, and sicknesses with

which the patient may be involved. There are about twenty people present. Everyone is given a seat and a plastic bucket, filled with a few inches of water, to

vomit in.

Learning the Medicine

When I lived with don Romulo Magin in his jungle hut, we drank ayahuasca together, sometimes with his son don Winister, also a shaman, as often as I could

stand it. The goal of the sessions was not healing but, rather, for don Romulo to

guide my visions with his songs, make sure I kept the prescribed dietary prohibitions, and protect me from sorcerers who might resent my presence. None of

my teachers was concerned that I myself might not become a healer; it is not

uncommon among mestizo shamans to follow the ayahuasca path as a personal

quest for learning and understanding., Indeed, mestizo shamans may periodically gather just to share their visions, trade magical knowledge, and renew

their strength.

NOTES

i. See Luna, 1986c, p. 51.

2. Luna, 1986c, p. 142; Luna & Amaringo, 1993, p. 43 n. 69.

THE MESA

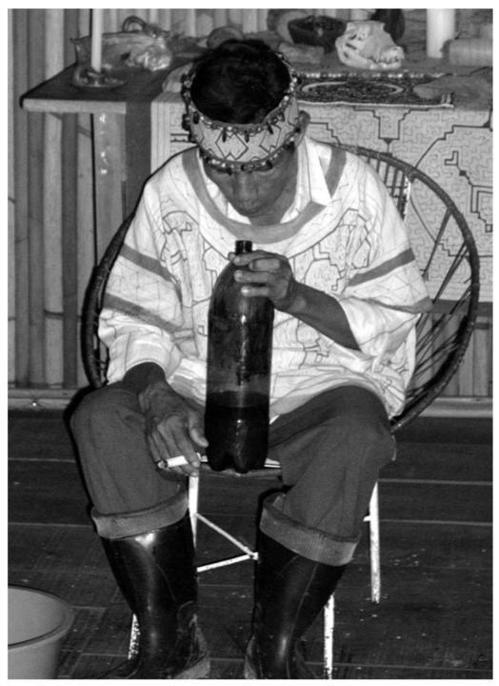

Don Roberto leaves and then returns, dressed for the ceremony. He is now

wearing a white shirt painted with Shipibo Indian designs, a crown of feathers, and beads. He smiles, makes a joke, and then spreads a piece of Shipibo

cloth on the ground, to form his mesa, table., On the cloth he places his ceremonial instruments:

• a bottle containing the hallucinogenic ayahuasca that will be drunk

during the ceremony;

• a gourd cup from which the ayahuasca will be drunk;

• a bottle of camalonga, a mixture of the seeds of the yellow oleander,

white onion, camphor, and distilled fermented sugarcane juice,

which he may drink during the ceremony;

• bottles of sweet-smelling ethanol-based cologne-almost always

commercially prepared agua de florida, but also including colonia de rosas and aqua de kananga-which he will use to anoint the participants

and which he also may drink during the ceremony;

• mapacho, tobacco, in the form of thick round cigarettes hand-rolled

in white paper, distinguished from finos, thinner and considerably

weaker commercial cigarettes;

• his shacapa, a bundle of leaves from the shacapa bush, tied together at

the stem with fibers from the chambira or fiber palm, which he shakes

as a rattle during the ceremony; and

• his piedritas encantadas, magical stones, which he may use during the

ceremony to help locate and drain the area of sickness in the patient's body.

PROTECTION

Don Roberto then goes around the room, putting agua de florida in cross patterns on the forehead, chest, and back of each participant; whistling a special icaro of protection called an arcana; and blowing mapacho smoke into the

crown of the head and over the entire body of each participant. Don Roberto

usually sings the same protective icaro at each ceremony. The song has no

special name; don Roberto simply calls it la arcana.

The goal is to cleanse and protect, on several levels. The arcana calls in the

protective genios, the spirits of thorny plants and fierce animals, and the spirits of birds-hawks, owls, trumpeters, screamers, macaws-which are used

in sorcery and thus the ones who best protect against it. Moreover, the good

spirits like-and evil spirits hate-the strong sweet smell of agua de florida

and mapacho, which thus both cleanse and protect the body of the participant. The goal, as don Roberto puts it, is to erect a wall of protection "a thousand feet high and a thousand feet below the earth."

PREPARING THE AYAHUASCA

Don Roberto sits quietly on a low bench behind his mesa, lights another mapacho cigarette, picks up the bottle of ayahuasca, and blows mapacho smoke

over the liquid. He begins to whistle a tune-a soft breathy whistle, hardly

more than a whisper-as he opens the bottle of ayahuasca and blows tobacco

smoke into it. The ayahuasca, don Roberto says, tells him-in the resonating sound of his breath whistling in the bottle-which icaro he should sing, and

he "follows the medicine." The initially almost tuneless whistling takes on

musical shape, becomes a softly whistled tune, and becomes the whispered

words of an icaro, which may be different at different ceremonies.

FIGURE 4. Don Roberto blowing tobacco smoke over the ayahuasca.