Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon (4 page)

Read Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon Online

Authors: Stephan V. Beyer

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Religion & Spirituality, #Other Religions; Practices & Sacred Texts, #Tribal & Ethnic

Maria told me of one dream from this period of her life, which remained especially vivid. She was very tired, she recalled, and went to bed early. She

dreamt that many people, adults and children, came and embraced her,

showed her many plants, walked with her in the mountains and on the

beaches. She played with these people in a beautiful river, and saw the sirenas,

the mermaids, with their long hair, and the beautiful and seductive yacuruna,

the water people, who live in cities beneath the water. Every day, she said, she

had dreams like this and became happy and unafraid of any animal or insect.

During this time, too, she frequently made up oraciones, prayer songs,

which she sang while walking to and from school. The other children, she

said, liked to hear her sing her prayer songs. Even at this time, she called these

songs her icaros-the term used not for prayers but for the sacred songs of

mestizo shamans. She also discovered that she could foretell the future; she

told me a story of how, when she was young, on a sunny day, she warned her

mother to return early from gathering beans in her swidden garden in the jungle because, as she correctly foresaw, a fearsome thunderstorm was coming.

This is the paradisal portion of dona Maria's narrative. She told not only of

her innocence and spiritual happiness but also of her turning away from evil.

She could have been a gran bruja, a great sorceress, she said; the evil spirit in

one of her father's magic stones gave her eight chances to turn toward sorcery, and each time she refused.

When Maria was nine, her father ran away with a brasilera, a woman from

Brazil. It is remarkable how frequently Peruvian men are said to run off with

Brazilian women-so remarkable, in fact, that I have come to believe that the

term brasilera is not meant literally, but is used as a generic pejorative term for

the type of woman who runs off with a married man. His sudden departure

left Maria, her mother, and her brothers and sisters all destitute; around this

time, too, perhaps due to the departure of the father, the family moved from

Lamas to Iquitos, where they lived a hand-to-mouth existence. At the same

time, Maria's dreams and visions were increasing in frequency and intensity.

She was frequently told by angels where there were sick children who needed

healing, and she was able to help her family with the offerings she received

from grateful families.

When she turned eighteen, dona Maria had the dream that was to influence her entire life-what she called her coronacion, her crowning or initiation. She told me each episode in the dream in precise detail, although the

episodes differed somewhat in different retellings. She was lifted up in her

mosquito net by the Virgin Mary and carried to the earthly paradise, where she

was greeted by thousands of white-robed angels, holding beautiful brightly lit

candles, lifting up their hands and saying amen in a single voice.

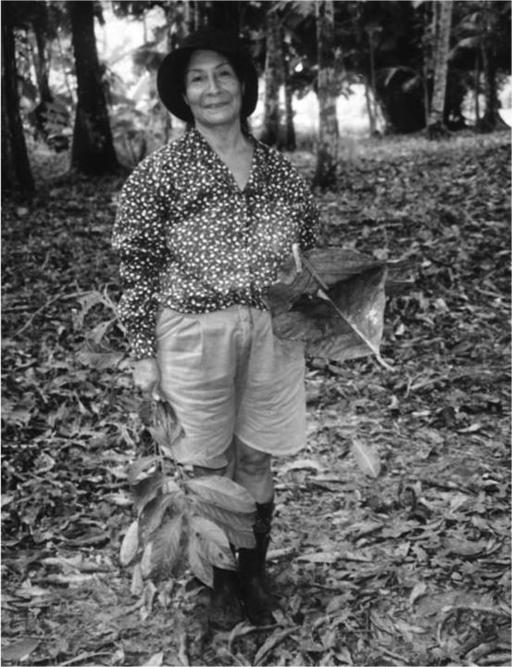

FIGURE 3. Dona Maria gathering plants.

Here she had numerous marvelous encounters-with magic stones, who

sang to her in welcome; with the suffering souls of aborted babies; with the

souls of the dead. They came to a great spiritual hospital where people greeted

her, saying, "We've been waiting for you. We are going to crown you because

you are a spiritual doctor." She was taken to a room where she was dressed in

white clothing, white shoes, and a surgical mask, and her hands were washed

with fragrant perfume. "You were brought here because you are a doctor

for the earth," she was told. "Tonight you will begin your work here and on

earth." She observed operations performed by the heavenly doctors, and was taken to a huge spiritual pharmacy filled with plant medicines of all kinds.

Again she was told, "Welcome, doctora. Tonight you are going to receive the

spiritual medicine." And everything that Maria saw and learned in the pharmacy she remembered when she awoke.

Finally, Maria and the Virgin came to two forking paths. One path was

filled with beautiful, fragrant, inviting flowers and led into the green valley;

the other path was filled with spiny and thorny plants and led to the rocky

and barren mountains. "Now choose a path," the Virgin Mary said. "Will it

be flowers or mountains?" Maria decided to take the path to the mountains,

on which she saw many plants she recognized from the earth, as well as many

that were new to her. The woman gave her a hug and kissed her forehead. "It

is the better path you have taken," she said. Maria and the woman held hands

and prayed. Maria felt emotion through her whole body and began to tremble.

"Do not be afraid," the woman said; and Maria saw that the rocky path was

in fact a precious highway, leading far away. "As far as you have come," the

woman said, "you have a long way to go. As of this day, you have the corona de

medicina, the crown of medicine"; and the woman placed a brilliant shining

crown on Maria's head. From the time of this initiation dream, Bona Maria

told me, she understood that she was no longer to heal only children, but

adults as well.

Ayahuasqueras

There are very few women shamans in the Amazon and certainly few among

the mestizos.' Dona Maria said that she had encountered very little prejudice

because she was an ayahuasquera. There were some shamans who said that

she should not be a healer, but, in her typical way, she said that those were all

stupid people with no fuerza, shamanic power, anyway.

Still, her vocation is rare. Rosa Amelia Giove Nakazawa, a physician at the

Takiwasi center who treats addictions with traditional Amazonian medicine, reports that, in twelve years of investigation, she has known only two women who

heal with ayahuasca. One is an elderly Quechua-speaking woman from Lamas,

who lives in isolation, feared in her village as a bruja, sorceress; the other is well

known in Iquitos but has fewer patients than the male ayahuasqueros, despite

the fact that their methods are similar.,

I know of just two female mestizo shamans-dona Maria and dona Norma

Aguila Panduro Navarro, who, until her recent death, performed healing ceremonies at Estrella Ayahuasca, her Centro de Investigaciones de la Ayahuasca y

Otras Plantas Medicinales between Iquitos and Nauta.3

One of the reasons for the scarcity of ayahuasqueras is a concern, widespread in the UpperAmazon, about menstruation; theShuarare perhaps unique

in making no distinction regarding ayahuasca use based on sex.4 Dona Maria

told me that the plant spirits-who dislike the smells of human sex, semen, and menstrual blood-will not go near a woman who is menstruating. The presence

of a menstruating woman at an ayahuasca ceremony, she said, will disturb the

shaman's concentration and impair the visions of everyone present. Such a participant can drink ayahuasca, but she will not receive the full benefit of the drink.

Blowing tobacco smoke on the menstruating woman-all over her body, beginning from the crown of her head down to the soles of her feet-may mitigate but

does not eliminate the problem. For the same reason, dona Maria said, a female

shaman cannot work while menstruating,

Such prohibitions are common in the Upper Amazon. Among the Piro, a

menstruating woman-or even one who has recently had sex-should not participate in an ayahuasca ceremony .5 Don Jose Curitima Sangama, a Cocama shaman, says that for the ayahuasca vine to grow properly, it must not be seen by a

woman, especially a woman who is menstruating, or has not slept well because

she was drunk. "If those women see the ayahuasca," he says, "the plant becomes resentful and neither grows nor twines upright. It folds over and is damaged."' For the same reason, don Enrique Lopez says that anyone undertaking

la dieta must avoid women who are menstruating, or who have made love the

previous night? Menstruating women must even avoid touching or crossing over

fishing equipment or canoes, lest they bring bad luck.$

There is less consensus regarding the effects of ayahuasca on a pregnant

woman. Dona Maria told me that drinking ayahuasca while pregnant gives

fuerza, power, to the developing child9 The same belief is found among the

Shuar: some women express the belief that a child is born stronger if it receives

the beneficial effects of ayahuasca while still in the womb.'° Elsewhere, because

of fear of spontaneous abortion, women do not drink ayahuasca at all." The Piro

agree; ayahuasca, they say, causes a pregnant woman to miscarry."

Some of these attitudes may be slowly changing, at least in some urban centers, in large part due to the effect of ayahuasca tourism. Female tourists who

have come great distances at considerable expense to attend an ayahuasca ceremony object strongly to being excluded because they are menstruating. There

are also an increasing number of ayahuasca retreats for women-only tourist

groups, and an increasing demand for female ayahuasqueras to accommodate

female tourists.

NOTES

1. On Amazonian women healers generally, see Giove, 2001; Zavala, 2001. For a comprehensive review of gendered shamanism among the Shuar, by a woman anthropologist who is herself an initiated Shuar shaman, see Perruchon, 2003.

2. Giove, 2001, p. 37.

3. Brief accounts of three female healers in the Iquitos area are given in Dobkin de

Rios & Rumrrill, 2008, pp. 95-98, 109-110.

4. Perruchon, 2003, pp. 222-223.

5. Gow, 2001, p. 138.

6. Quoted in Dobkin de Rios & Rumrrill, 2008, p. 61.

7. Quoted in Cloudsley & Charing, 2007.

8. Hiraoka, 1995, p. 213.

9. See also Giove, 2001, p. 39.

10. Perruchon, 2003, p. 223.

11. For example, Siskind, 1973a, p. 136.

12. Gow, 2001, p. 138.

The Meeting with Don Roberto

At the age of twenty-five, Maria was attacked by an angry and envious sorcerer,

one of whose victims she had healed with her prayer songs. She was struck by

his magic darts, one in her throat and two in her chest, which penetrated so

deeply that she could not talk and could scarcely breathe.

Dona Maria spoke frequently about other people's envidia, envy, at her successes as a healer, and their unwillingness to share with her. There are three

sins that characterize most adults, she said-envidia; egoismo, selfishness;

and ambicidn de la plata, greed. When she calls the spirit of an adult, she told

me, the spirit feels like a wind; but when she calls the lost soul of a child, it

appears as an angel, because children are innocent of these sins.

She frequently compared her own openhandedness with the selfishness

of other shamans, who do not want to reveal their icaros, their magic songs.

"I'm not selfish," dona Maria said. "I sing loud because I'm not afraid to let

people know what I know." She frequently spoke of her own practice as pura

blancura, pure whiteness, compared with the black or-even worse-red

magic practiced by other, less disciplined shamans. Her attack by this brujo

was the result of his envy and resentment; her later attack by don X, as we will

see, was the result of his resentment and greed.

During this first magical attack, she went to the cemetery and prayed, cried

out to all the almas olvidadas, the lost and despised souls, to help her find a

shaman to remove the darts that had been shot into her body. Around three

o'clock in the afternoon, a friend came to Maria's house; Maria could barely

speak to her, because of the darts that had been shot into her throat. The

friend offered to take Maria to meet a shaman she knew-a man named don

Roberto.

It was Sunday when she came to don Roberto's house. When she knocked

on the door, Don Roberto opened it and said, "Welcome, sister. I have been

waiting for you." He continued: "Sister, I knew you were coming. Your body

is fine, you are strong, you know much about the spirits, but you lack defense. Ayahuasca will give you defense." He told Maria how he had just cured

a woman of sorcery, inflicted on her by the use of a manshaco, a wood stork.

Then he sucked out the three darts. He gave one of the darts to Maria, putting

it safely into her body through her corona, the crown of her head. He said,

"Sister, this one is for you. I will keep the others."

Don Roberto told her, "Sister, you are very strong, but you do not yet know

ayahuasca. If you come to me on Tuesday"-Tuesday and Friday nights are

the traditional times for ayahuasca healing ceremonies-"I will introduce you." On Tuesday she drank ayahuasca with don Roberto, had a very powerful

purge, and started on the ayahuasca path as his apprentice, along with five

men and four other women who were already working under his direction.

"Now you will work with ayahuasca in addition to what you are doing," don

Roberto told her, "and you will move forward."

Dona Maria worked with don Roberto for ten years, until she was thirtyfive years old, learning ayahuasca. This was a time, she said, of pura medicina,

pura blancura, only medicine, only whiteness; nada de rojo, nada de negro, no

red or black magic. After these ten years, don Roberto decided to return to his

chacra in the jungle; but even when they were separated, dona Maria said, they

continued to call upon each other from afar for help in their work.