Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher (39 page)

Read Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Having lost Muhr, his photo-finisher, Morgan, his patron, and Upshaw, his translator;

having had Phillips, his field stenographer, and Schwinke, his cameraman, go off to

other callings, Curtis counted on Myers as a brother in The Cause. Myers was his second

self, his ghost in the writing, his chief ethnologist, journalist, editor and wordsmith

combined, the only person alive who knew the work as well as Curtis, who bled the

project. What’s more, he and Curtis truly got along. After almost twenty years together,

“we never had a word of discord,” Curtis wrote.

The North American Indian,

with its exhaustive accounts of languages, customs and histories that had never been

fully recorded, might never have existed without Myers. Not only was his work ethic

extraordinary, matching Curtis in long hours, but his temperament was suited to the

thankless task. He rarely complained. But it was all over now.

“Like a bolt of lightning out of a clear sky” was how Curtis described the news to

Hodge.

He paid tribute to his partner in the introduction to Volume XVIII, the last book

to which Myers contributed. “In the field research covering many years, including

that of which the present volume is the result, I have had the valued assistance of

Mr. W. E. Myers, and it is my misfortune that he has been compelled to withdraw from

the work, owing to other demands, after so long a period of harmonious relations and

with the single purpose of making these volumes worthy of the subject and of their

patrons,” Curtis wrote. “His service during that time has been able, faithful, and

self-sacrificing, often in the face of adverse conditions, hardship, and discouragement.

It is with deep regret to both of us that he has found it impossible to continue the

collaboration to the end.” Myers wept when he read the dedication.

The new kid was just out of the University of Pennsylvania, a native of Vermont. Did

he know anything about the West? About Indians? About ethnology? Not much, as it turned

out, but Stewart Eastwood had taken some anthropology classes and had come highly

recommended by an authority on “Eastern Woodland Indians,” as his résumé said. Eastern

Woodland Indians? Who the hell were they?

Curtis had tried to lure Hodge out of the office to take up the final fieldwork with

him, knowing he liked to flee the city, particularly for trips to the Southwest. But

Hodge had a full schedule at the museum, so he vetted the Ivy League kid and sent

him out to Oklahoma to meet the Shadow Catcher. It was a rough go. Eastwood joined

Curtis at a large intertribal gathering in the flat light of Oklahoma. They spent

weeks working sources, looking for faces to shoot, stories to tell. It was depressing.

“The program is tentative,” Eastwood reported back to Hodge, “we are up in the air

since so many problems have arisen . . . The five civilized tribes are so much civilized,

so white, that they will be impossible while the wealthy Osage are not only becoming

civilized but wealth gives them a haughtiness difficult to overcome.” It was a problem,

this business of civilized tribes and tribes grown rich from oil discoveries on tribal

land. Curtis noted that “idle wealth” was like a disease among the Osage; the men

were chauffeured around in new cars, while the women—in an ironic twist—employed poor

whites as their housekeepers.

The Wichita were another kind of problem. Mormon and Baptist missionaries had been

all over them, and as a result, many tribal customs were now banned as pagan rituals.

Their practice could mean a sentence to hell. “Couldn’t even take a picture of one

of their grass houses,” Eastwood complained. (Curtis eventually managed to shoot that

very image, titled

Grass House—Wichita,

for Volume XIX.) Tribe after tribe, it was the same story—no story. The past had

not only been banished but wiped away, no trace of it in this new land. The urgency

of his work over nearly a third of a century, always in a hurry to stay one step ahead

of “civilization,” was never more justified than in Oklahoma. There, Curtis saw his

worst fear; it was why he’d lamented, time and again, that with each passing month

“some old patriarch dies and with him goes a store of knowledge and there is nothing

to take its place.”

No tribe in the country had fallen so far as the Comanche. Once, as masters of an

enormous swath of flatland, they had forced Texans to retreat behind settlement lines

and Mexicans to run at the sight of them. Indians from other tribes would slit their

own throats before allowing themselves to be taken prisoner by a Comanche. There were

no better buffalo hunters, nor more efficient warriors, than this tribe. They reveled

in scalping and torture of enemies, particularly fellow Indians without battle skills.

Their raids for wives and horses were legendary, going after the Apache, the helpless

Five Civilized Tribes and assorted natives up and down the Rio Grande and north into

Kansas and Colorado. All of it was carried out with an exuberant “blood lust,” as

Curtis wrote. The sight of the Comanche now, forced into stoop labor, raising chickens

on a reservation in Caddo County, Oklahoma, was pathetic to Curtis. “The old wrinkled

men,” he wrote, “sit about and tell of the days of their ancestors when life was real

and full of action.” The best he could do was to concentrate on portraits. Only in

the faces could Curtis find some hint of the authentic. He did not care if they appeared

before his camera in starched shirt and tie; what fear the Comanche still struck in

the hearts of others would have to emanate from a glare that carried a sense of menace

from their grandparents.

The text was a struggle from start to finish. Hodge judged it an inferior work and

asked for a major rewrite. He complained to Eastwood about his spelling, accuracy,

sentence structure and the paucity of new information. It was a mess. They clearly

needed Myers’s hand. And Myers himself was sorry that the work had suffered so much

from his departure, feeling author’s remorse. “I am distressed by your report on vol.

19,” he wrote Hodge, “it really causes me regret that I yielded to the lure of Mammon.”

By early 1927, after hammering away at Eastwood, Curtis felt the kid was improving,

though he was not holding up well to the withering critiques from Hodge. Eastwood

threatened to quit.

“You’re a good editor but a bum diplomat,” Curtis wrote Hodge. “It has taken a lot

of quick figuring and hard talking to keep the boy in line. To have him drop out at

this last moment would wreck the ship.” Hodge insisted they keep their standards high

this close to the end. “There is no need of being thin-skinned in a work of this kind.

The manuscript is either right or wrong, and if wrong should be righted.” The writers

went back to their notes, but it was hard to find water when the well was dry. As

they closed out the editing, Curtis conceded that Volume XIX probably would not stand

among the rest. Time had robbed him of the chance to find the pulsing heart of Indian

life in the state with more Indians than any other.

“You say the Comanche material is inadequate,” he wrote Hodge in a testy exchange.

“I grant you that it does not make a strong showing, but one cannot make something

from nothing . . . The only material we could find was countless, meaningless, fragmentary

obscene stories of the camp fire type.”

There remained one chance for redemption: to finish on a high note in the far north.

Alaska had held a special place in Curtis’s heart ever since his sea journey there

with the Harriman expedition of 1899. He was thirty-one then, still on the boyish

side of manhood. The gimpy-legged graybeard of 1927 who made plans for the final field

trip of

The North American Indian

was broke, divorced, a year shy of his sixtieth birthday. He had a lifelong nicotine

addiction and the smoker’s hack to go with it, as well as assorted grumpy complaints

about his bad fortune at this stage of life. And yet in one respect he moved as he

always did: confident in motion itself as the animating virtue of his existence. Beth

would finance the trip with money from the studio and from her husband, Manford Magnuson,

whose own portrait photography business was doing well. The latest home of the Curtis

studio was the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles, which gave it a glamorous address for

the stationery and was a prime spot for tourist traffic. Visitors from the East or

from Europe needed to go no further than the lobby of their downtown hotel to purchase

a Curtis Indian, the kind of picture that would generate stories back home and become

an heirloom in time.

The new plan was to sail from Seattle to Nome, a fogbound seaport in Alaska Territory,

ice-free only a few months of the year, within easy distance of the Arctic Circle.

From Nome they would branch out to the Bering Sea, to islands and cliffs, in search

of Eskimo people, all the way to the Siberian shore. They could work sixteen-hour

days in the midnight sun, Curtis reasoned, and stretch the season out until the first

snows of September. “Good fortune being with us we may, by working under great pressure,

manage to finish the task in one season,” Curtis wrote. The college kid, Eastwood,

signed on for a second go-round despite his difficult rookie outing in Oklahoma. The

joy for Curtis was the first assistant, his daughter Beth. For much of her life she

had dreamed of spending time in the wild with her father. Florence had gotten to experience

him in action in California. Now it was Beth’s turn. When Myers heard of the final

launch of

The North American Indian,

he was sick with regret, killing time in San Francisco, his real estate deal yet

to come together.

“Curtis writes me that he is leaving for Alaska,” Myers told Hodge. “I wish I were

going.”

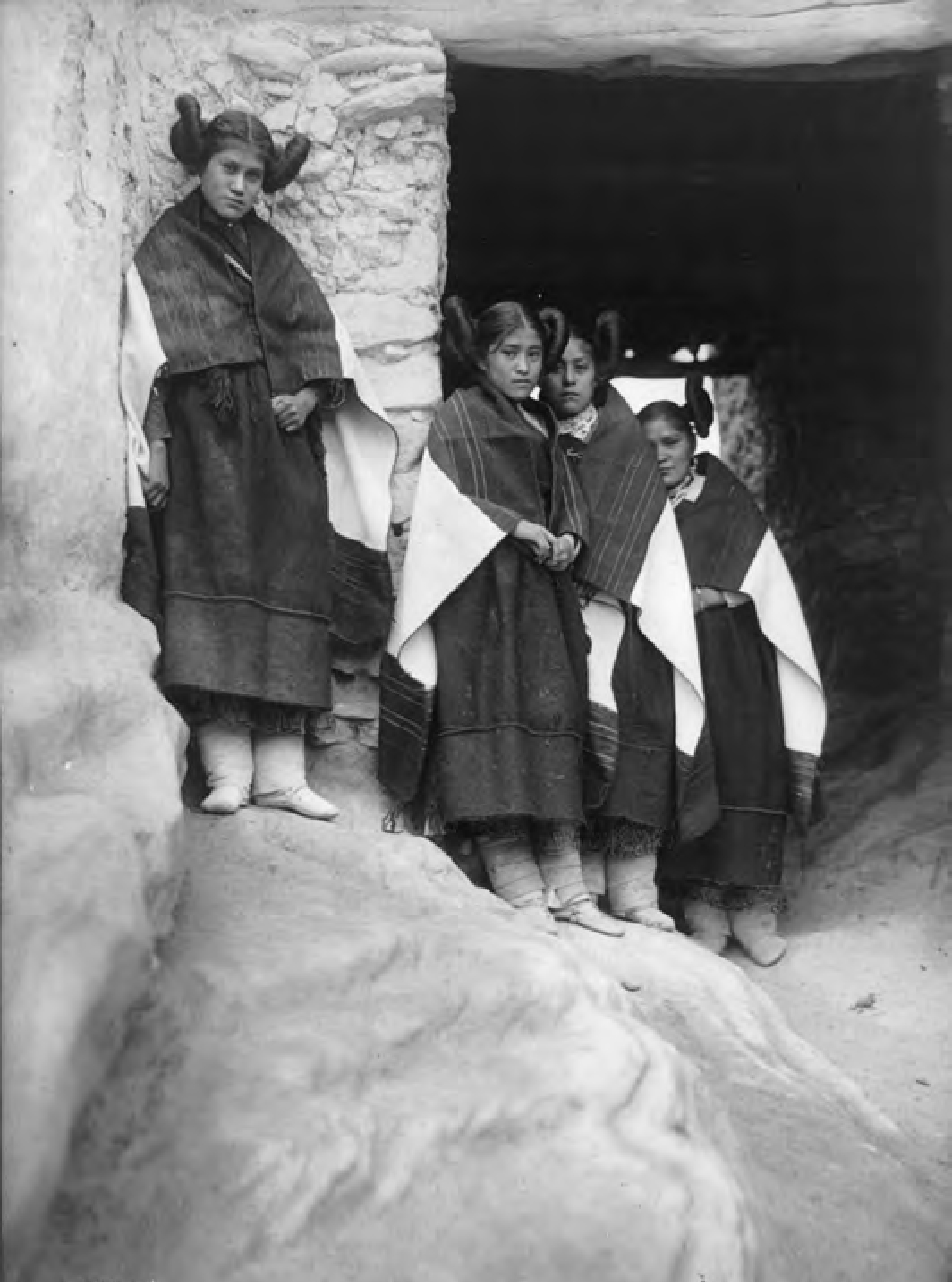

1906. The young women wore their hair in squash blossom whorls.

1906. Curtis returned to the Hopi Nation more than half a dozen times, until his

presence was barely felt. These women lived at the summit of the stone village of

Walpi, in Arizona.

1923. In northern California, after many years in which his grand project was at

a standstill, Curtis was revived by a trip with his daughter Florence back into Indian

country.

1927

T

HE STEAMER VICTORIA

left Seattle on June 2, 1927, bound for Nome and ports in between, a journey of 2,350

miles by sea, a bit shorter than a trip by train from Puget Sound to New York. The

rail travel cross-country could be made in four days. The passage to northern Alaska

was supposed to take ten. A late-spring drizzle misted over Elliott Bay as Curtis

and his daughter posed on deck. He was in suit and tie, with a thick woolen overcoat,

cigarette in hand. Beth wore a flapper’s cap, a fur-collared jacket and a cocky smile

that bore her father’s DNA. “It truly seemed as though I was going to the other end

of the world as the boat pulled out from the wharf and I was finally on my way for

the much longed for trip with Dad.” Both father and daughter kept diaries. For Curtis,

it was the only time he wrote a day-by-day account of his activity, and he even gave

it a title: “A Rambling Log of the Field Season of the Summer of 1927.”