Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher (36 page)

Read Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

The studio was the crown jewel, for now, of what had been a Curtis empire. In 1916,

just before the divorce papers were filed, it had moved to a new location, at Fourth

and University, perhaps the most prestigious address in the city, where the University

of Washington had its original campus. Across the street were the Indian terra-cotta

heads of the Cobb Building, a Beaux Arts beauty completed in 1910. The Indian heads

were a tribute to Curtis. A hotel that was destined to be the city’s finest, the Olympic,

was rising on another corner. The studio was a must-stop for educated tourists visiting

Seattle. Inside, light flowed through large windows, illuminating the inlaid wood

floor, the stunning designs of Navajo rugs and the numerous portraits in the gallery.

Beth Curtis, just out of her teens, oversaw the operation. In a few short years she

had gone from apprentice to boss, a source of many disputes with her mother, who had

tried to keep a hand in the family’s most valuable asset. Here, orotone prints were

refined and rebranded as Curt-tones. This process, used only rarely by Curtis, involved

printing an image directly onto glass instead of paper, then backing it with a gold-tinged

spray. Curt-tones were more fragile, but could also command a much higher price; the

finish jumped out of the frame.

Beth tried to keep her mother, who was full of rage, at arm’s length. As Beth had

risen, Clara had been marginalized. She would show up at the studio steaming, and

start harassing employees. Beth was embarrassed; customers were shocked at the shouting

matches, the accusations. To Beth it seemed that her mother was on a campaign of intimidation

designed to drive the daughter from the business or to bring the whole enterprise

down. On an April day in 1919, Clara stormed into the studio, moving with a single

crutch. She had been injured, she said, and it was because of the strain of the broken

marriage and family strife. When Beth approached her, Clara attacked her with the

crutch. Employees were stunned—mother and daughter coming to blows, a combustion of

screeching and flailing arms.

When

Curtis v. Curtis

was finally settled in June of 1919, Clara got the house and the studio. The judge

ordered Curtis to pay her $100 a month in child support. She had been unrelenting

in going after what she felt was rightfully hers after nearly a quarter century of

marriage, and the court agreed with her. Since filing to end the marriage in 1916,

she had requested preliminary financial help, but Curtis was unresponsive. In 1918,

she asked that he be held in contempt for failing to pay alimony. “I am practically

destitute and dependent upon friends and relatives for support,” she wrote. As one

example of her sorry state, she said her youngest child was in need of dental work,

but there was no way to raise the $300 for it. She had also sued Beth, claiming her

oldest daughter was in cahoots with Curtis to deprive her of income. In Beth’s response,

she said Clara had gone mad. She detailed the ugly visits in the studio when Clara

tried to “harass patrons” and “greatly embarrass” Beth. It came to a head with the

assault. Yes, there was plenty of vitriol, even some violence, Clara agreed—but for

good reason. She said Beth had been secretly funneling money to her famous father.

“He is in the habit of going from place to place all about the country, living in

a manner befitting his reputation and his pretentions.” In truth, Curtis was living

more like a hobo, sleeping under the stars more often than he was beneath the roof

of a hotel; without permanent address or paycheck, he wandered the West.

That same year, Curtis lost the most powerful and influential of all his backers,

Theodore Roosevelt. The president died in his bed at Sagamore Hill at the age of sixty,

a relatively young man who had lived a dozen lives in his three score years. Curtis

had tried to maintain his ties to Roosevelt after the president left office in 1909.

He sent him notes and pictures, always addressing him as “My Dear Colonel Roosevelt,”

as T.R. preferred to be called postpresidency. But starting about 1915, the notes

became excuses of a sort, Curtis apologizing for being late with a promised photograph

or claiming once that he had nothing to do with someone who had petitioned Roosevelt

to speak on Curtis’s behalf. This most energetic, athletic and prolific of presidents

died of an embolism in the lung—a blood clot. Other maladies surely took their toll.

He had carried a bullet in his chest since a would-be assassin shot him during a speech

in the frenetic 1912 Bull Moose election campaign. The gunman’s slug was deemed too

deep, too close to vital organs, to remove. Roosevelt’s trip to an uncharted and malarial

river in the Amazon—“I had to go, it was my last chance to be a boy”—had nearly killed

him, and he never had the same vigor afterward. But it was the death of his son Quentin,

an aviator for the Allies who was shot down by the Germans in a war Roosevelt righteously

promoted, that left him so bereft of spirit, a Shakespearean ending.

For Curtis, losing the studio was the lowest blow. His countless negatives and glass

plates, the many prints he had labored over with Muhr—they were part of “the property.”

What would Clara, still seething and capable of assaulting her own daughter, do with

these treasures? Beth, apparently, was unwilling to take that chance. Rushing to act

before the keys were turned over to her mother—and moving ahead with the approval

of her father—Beth and several employees worked nonstop to print up dozens of Curt-tones

of some of the more iconic images and shepherd them off for safekeeping. Then, trunkloads

of glass negatives were taken across the street to the basement of the Cobb Building

and destroyed. It is unclear why this was done—was it to prevent Clara from going

out on her own with all the Curtis property she’d won in the divorce, as some family

members have said?—but what is known is that hundreds of plates were smashed to pieces.

The tired sun of Hollywood was not the ideal cast for a man who once waited days

for a single instant when natural light held the world a certain way. But Curtis was

now being paid by how quickly he produced a picture, and so better to move it along.

Here was Tarzan in 1921, looking ridiculous in leopard-skin loincloth, fake vines

in the foreground, blowing a flute. A flute! The job that kept Curtis going in 1921

found him shooting the actor Elmo Lincoln, who starred in a series of Tarzan movies

at the height of the silent picture era. Lincoln had made a name for himself in

The Birth of a Nation

and

Intolerance,

two of the best-known works of D. W. Griffith, and he could be a pain.

For Curtis, Los Angeles was now home. He opened a new office at 668 South Rampart

Street, a few blocks from some of the major film studios. It was just Curtis and his

daughter. Beth ran the business side. Curtis labored over portraits of character actors

and cowboy stars, film directors and minor starlets. He needed a fresh start, and

Hollywood, with a steady payroll for pictures, seemed like the best place. It meant

something, still, to have “Curtis” written across the bottom of a photograph, with

the familiar fishhook signature. The jobs came at an uneven pace and did nothing to

stir Curtis’s blood. It was hackwork. He processed the pictures out of his home. One

of the great ironies to beset his own film was that shortly after

In the Land of the Head-Hunters

was released, the commissioner of Indian affairs announced that the government would

no longer allow filming of Indians in “exhibitions of their old-time customs and dances.”

Hollywood went back to featuring Italians and Mexicans in pulpy westerns shot on back

lots not far from where Curtis now lived.

Curtis was a middle-aged, divorced man trapped by bad luck, he told a friend, without

spare cash even for a train ride to Arizona. The piecemeal work paid the bills, and

kept the “Home of Curtis Indians,” as it said on the stationery, a going concern.

What that meant was that—someday—there might be enough money to spring him from Los

Angeles. At first he did only movie stills, though he certainly knew his way around

any device to record an image. Tarzan was a big client. Curtis tried to bring some

dignity to the work. He posed the shirtless actor straddling a stream—the familiar

water motif—each leg on a rock. The studio wanted the leopard skin, and the damn flute.

Who was Tarzan calling? Would creatures of the African wild respond to a summons from

a white guy with a delicate instrument? These were not questions for Curtis to answer.

His job was to take the publicity shots and go on his way.

In time, he found work from some of the biggest names in Hollywood, most prominently

Cecil B. DeMille. For the great director, Curtis took photographs of

The Ten Commandments

in production, and also did some of the field research, such as it was. A beach in

Santa Monica became the Arabian sands. Much later, DeMille gave Curtis acknowledgment

as a second cameraman on the film, though he never got a screen credit. A few of the

Hollywood pictures that remain reveal a dash of Edward Curtis—a high-drama chariot

scene, blue-toned pictures that convey plenty of betrayal, lust and intrigue, and

a handful of arty nudes.

Curtis never thought of Hollywood as anything but a sad, single-business town full

of hustlers. He recognized the type. Everyone had a screenplay, of course. Even Meany

inquired about getting some of his stories onto the screen. Good God. Curtis responded

in blunt terms.

“The scenario schools and rewrite crooks keep leading people to think that there is

a market for stories,” he told Meany. “I know good writers who have from a dozen to

50 good stories on the market and have not sold one in three years.”

Meany was by then a beloved figure in the Pacific Northwest; a mountain in the Olympic

range would be named for him, as would Meany Crest on Rainier. He’d found it difficult

to maintain his friendship with Curtis after the photographer left Seattle in 1919,

because Curtis did not hold up his end. He fell out of touch, a slight. He also succumbed

to depression, a fog that made him feel helpless and humiliated. In correspondence,

and in the eyes of many who had considered him an American master, Curtis was a dead

man.

When Meany heard in 1920 that Curtis had slipped into town, he dashed down to the

Rainier Club, only to learn that Curtis had already left for the train. The professor

ran the half mile to King Street station, but just missed him. Later, he heard that

Curtis had suffered a complete breakdown, his depression leaving him unresponsive

and unproductive through some of the Hollywood years. That would explain why he was

afraid to see Meany, and would go years without writing him.

“My good friend,” Meany wrote Curtis in 1921, “I certainly wish you more happiness

than has been your portion of late.” For all the lapses and holes in their friendship,

Meany kept working on the relationship, though Curtis continued to shun him. Sam Hill,

the quirky railroad millionaire, suggested to Meany that Curtis could make a bit of

money touring reservations with an Indian-loving Frenchman of his acquaintance, Marshal

Joseph Joffre, an Allied commander during the Great War. Hill lived in Seattle and

was an early Curtis backer. He was best known for erecting an enormous castle along

the treeless, windswept hills in the eastern part of the Columbia River Gorge and

then stuffing it with Rodin sculptures and live peacocks. Curtis felt the suggestion

demeaning. What, was he now some tourist guide for entitled toffs?

Hill’s idea prompted the first letter Curtis had sent to Meany in a long time. “I

fear this is not possible,” he wrote in January of 1922. He was feeling low, empty

and angry, and couldn’t let any of it go. “Mr. Hill, always having an ample bank account

at his command, is scarcely in the position to realize the situation where one has

to produce something today or not eat tomorrow.”

1915. On the far western edge of the continent, Curtis loved the inherent drama of

fishing and whaling. The whaler is Wilson Parker, dressed in traditional bearskin,

with the spear and floats used in the hunt.

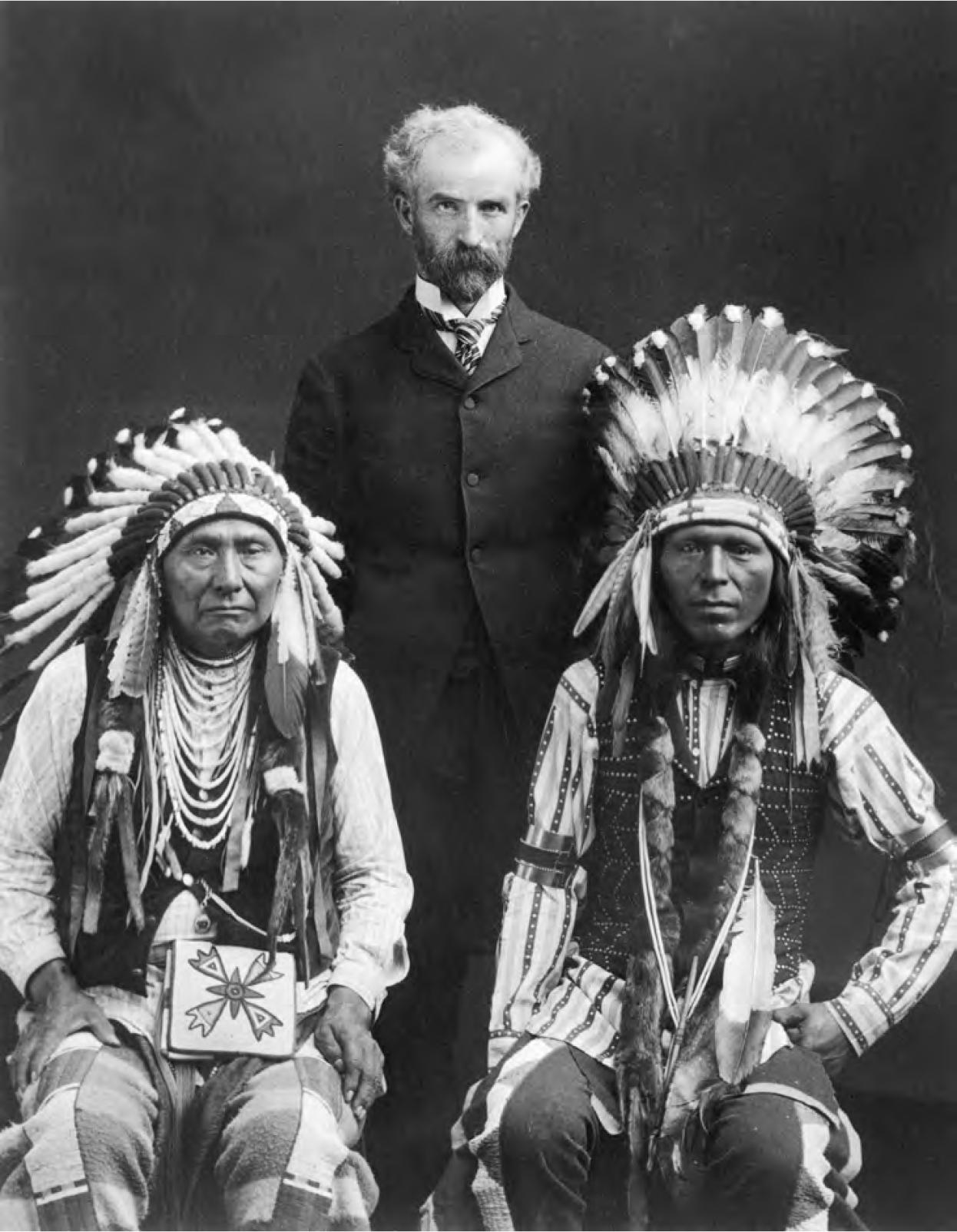

and despair with his friend Edward Curtis. Here he poses with Chief Joseph and Joseph’s

nephew Red Thunder in a picture taken by Curtis in his studio in 1903.