The floating population, deracinated rural workers and beggars,

mangliu

in Chinese, became an increasingly major social problem as the economic Reforms continued in the 1980s and 1990s. Urban dwellers often spoke of the masses of roving peasants (tens to hundreds of millions depending on what sources you accepted) as being a major threat to social stability and future prosperity. Some mangliu, however, believed that it was from their ranks that a new strongman, someone perhaps with the stature of Mao Zedong, would eventually appear to rule the nation.

|

Mao himself had an early career as a

mangliu

of sorts, details of which are recorded in a book by his companion at the time, Siao-yu.

1

In the 1990s China's floating population armed itself with the invincible weapon of Mao Thought, or as a popular rhyming saying put it:

|

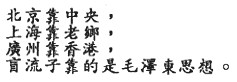

|  | Beijing kao zhongyang,

Shanghai kao laoxiang,

Guangzhou kao Xianggang,

Mangliuzi kaode shi Mao Zedong sixiang.

|

|  | Beijing relies on the Center,

Shanghai on its connections,

2

Guangzhou leans on Hong Kong,

The drifting population lives by Mao Zedong Thought.

3

|

In February 1995, the Australian-based Chinese journalist Sang Ye, co-author with Zhang Xinxin of

Chinese Lives: An Oral History of Contemporary China,

4

was back in China working on a new volume of interviews. His subjects included a

mangliu

who spoke of the venerable pedigree of

mangliu

in Chinese history.

5

|

In fact, the founding emperors of all China's dynasties were

mangliu.

Chairman Mao was a big

mangliu.

When he first came to Beijing from Hunan, [the leader of the Communist Party] Chen Duxiu and [Mao's wife] Yang Kaihui's father were well-known professors. They made hundreds of

|

|