Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire (34 page)

Read Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire Online

Authors: Eric Berkowitz

There was no military need for Balboa to commit these murders. The local king had already been liquidated, and Spanish power in the area established. The story had much more to do with public relations at home than with military strategy. By repressing native sodomy, the conquistadors were able to claim that they were doing God’s will. Not only were they rampaging for plunder, they were also righting moral wrongs. Interestingly, the earliest account of this massacre frames the entire affair as a merciful liberation of good natives from corrupt courtiers. When the common folk learned what the king’s brother and his men had got up to, they “begged [Balboa] to exterminate them, for the contagion was confined to the courtiers and had not yet spread to the people.” The natives reportedly raised their arms to heaven and expressed their understanding that “this sin” caused “lightning and thunder” as well as “famine and sickness.”

To believe this story is to accept that the native population of Panama had already read and embraced Leviticus, with its message that God rains down hellfire everywhere sodomy takes place (as he had done to Sodom and Gomorrah), recalling it as they were being attacked by Spanish soldiers. But veracity was not the point. As the destroyer of sodomites everywhere, Balboa was portrayed as morally correct not only in killing the king’s brother, but also in protecting the local populace from God’s anger.

Upon landing in Mexico in 1519, the conquistador Hernán Cortés described the local populace in blunt terms: “They are all sodomites.” In every village he entered, Cortés called for sodomy to be abandoned and Christianity adopted. He was equally frank with the Aztec leader Moctezuma, whom he exhorted to halt the “abominable” sin of sodomy in his lands. Of course, there was no suggestion that the rape of native women was just as improper; Cortés handed out “Caribs” to his captains just as Columbus had done a generation earlier—although the women were baptized before distribution. (One of them later had a child by Cortés himself.) To Cortés, sexual conquest and the eradication of sodomy were one and the same thing.

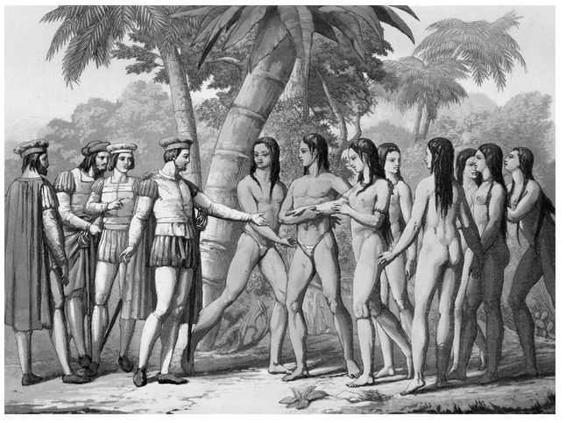

THE FRUITS OF CONQUEST

During the age of exploration, the New World was depicted as a humid sexual playground full of willing females ready to “debauch and prostitute themselves” for the pleasure of European men. This image shows Christopher Columbus receiving a comely native girl as a “gift.” The other young females seem ready to give themselves to the explorer’s companions.

©TOPFOTO

The linkage of enemies with ungodly sex was nothing new. In 1492, the year Columbus first sailed to the Western Hemisphere, Christian leaders finally regained full control of the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim rulers after centuries of trying. As the mass expulsions and murders of Muslims and Jews commenced, both groups were broadly accused of committing and condoning sodomy. To the Spanish and Portuguese, the natives of the New World were also cut from sexually incontinent cloth, and deserved no less to be extirpated. While Balboa, Cortés, and their like killed accused sodomites in the West Indies, thousands more were being burned and castrated throughout Iberia.

In the early years of overseas conquest, the New World was, at least for heterosexuals, a lawless place where a man could indulge in sexual adventures. Yet this dynamic could not last. Law abhors a vacuum, and the joys of sex without consequence were short-lived. With the establishment of settlements, trading posts, and ports, Europeans mixing with native populations soon generated offspring. As white, black, and brown combined to create new human incarnations, the laws also had to change color.

4

GETTING CLOSE TO THE NATIVES

Take a man from his home, put him on a lengthy, dangerous sea voyage, and then drop him on a beach with barely clad native women, and he will forget that fornication and adultery are forbidden. Thousands of miles away from tradition, mothers, and wives, the panoply of European laws limiting sexual behavior (especially those barring sex with non-Christians) was jettisoned as unnecessary ballast. As one thing follows another, the men often came to realize that indigenous women were much more than objects to be raped and discarded. Many colonists and sailors formed deep relationships with them—attachments that demanded that traditional norms regarding sex, marriage, and children be reexamined on the fly.

Throughout the period of European conquest in Africa and the New World, the law was simple: No sex outside marriage was allowed, and sex or marriage with non-Christians was a serious crime. Carnal relations with Muslims, for example, were a capital offense in Portugal and Spain, and sex with Jews was proscribed almost everywhere. The penalties ranged from small fines to banishment and execution, depending on the location and the status of the men and women involved. For example, sex with Muslim women was punished by death in Modena, Italy, except when the women were prostitutes—in which case the male customer was to be merely thrown in jail for the rest of his life and deprived of all of his property.

Of course, the existence of laws does not mean they were always followed, much less vigorously enforced, and there was often a gap between the harshness of the rules governing sex and the punishments actually meted out. The rules against sexual congress with non-Christians were transgressed everywhere such people were encountered, and unless the couplings were too obvious or somehow upset the broader social order, most of them went unpunished. A furtive union between a Christian and a Jew in Spain, for example, was likely to be overlooked so long as it remained quiet. If the affair grew into something resembling marriage, the risk level also grew. While Vespucci and his ilk touted the New World as a paradise of sexual opportunity, they referred only to short-term carnal fulfillment, not lasting marriages. No one disagreed that these relationships crossed every moral and legal boundary, but they happened anyway. What to do?

In West Africa, where many colonists were Portuguese

degredados

(convicts put onto boats rather than executed), official responses to intimate affairs with natives were inconsistent. Many of the men in charge of the Portuguese enterprises were sexual adventurers themselves. Bishop D. Gaspar Cão, for example, was accused of keeping concubines of many races. In the early 1500s the Portuguese Crown began appointing married men to the

capitanías

on the assumption that they would be less inclined to sexual excess, and would set a good example. One such appointee, Fernão de Melo, came to the island of São Tomé to succeed his predecessor, who had lived for years with a slave and a concubine. De Melo brought his wife and children, but kept them locked in a stone tower for their own protection against unruly colonists and foreigners.

The Portuguese who came to Africa were strongly attracted to native women. Time and again, the Portuguese home authorities sent white women to entice the colonists away from natives, but these efforts often met with failure. First, female prisoners were brought over in the hope that they would mate with the

degredados

and populate the settlements with white people. No such luck was to be had. The Crown then sent thousands of Jewish adolescents who had recently been expelled from Spain, hoping that they would marry

degredados

and spawn children. Again, the plan failed. Many of the Jews died, and the survivors proved incompatible with the

degredados.

In fact, both groups preferred the company of natives.

The Portuguese Crown also tried to prevent its colonists from bonding with natives by providing them with cheap prostitutes and slaves. Unattached and well-paid “castle women” were also made available to work in the settlements and, it seems likely, to provide for the colonists’ personal physical needs as well. Both of these policies put the Crown in the sex business, but that was preferable to allowing its subjects to form families with Africans. Yet these efforts failed, too. The slaves and castle women did their jobs—they had not been hired for good conversation—but that did not prevent interracial marriages from taking place. As happened elsewhere, religious authorities grudgingly relented and approved the unions provided the native women were baptized and renounced their former lives. But cultural adjustments after marriage sometimes went in the opposite direction. Some of the men left the colonies entirely, settled inland with their wives, and assumed native ways. They became known as

tangosmaos

, a derogatory term implying the worship of fetishes.

Once married white men took up lasting relationships with native women, the question turned to the fates of their families back home. Which family had greater claim to the men? Which children inherited their property? If the African women were technically slaves (which was not always clear, especially when the men had “paid” for their wives), the law always gave preference to their husbands’ legitimate families. Once she learned what her husband was up to in her absence, a Portuguese wife could turn to the courts to force him to sell his black wife and mixed-race children. However, in the haze that existed between the European and colonial worlds, the certainties of the law were often obscured. Stationed for extended periods in the tropics, even the most elevated members of colonial society formed profound ties with women who would otherwise have been considered unsuitable as wives, and the law was often at a loss as to how to deal with them.

When the Portuguese captain of São Tomé, Álvaro de Caminha, died in 1499, he left a will that evoked a welter of emotional entanglements. First, he provided for the manumission of Isabel, an African slave to whom he seems to have been deeply attached. He also left her money and a slave child of her own. In the same document, de Caminha left money, furnishings, and several slaves to Ursula, a converted Jew he also loved deeply. Ursula had been in his employ, and while she was not technically his wife, he had lived with her in harmony for some time. De Caminha’s will suggested a suitable marriage partner for her and included a letter of introduction to a convent, in the event she decided not to marry and become a nun instead. Most remarkably, the will specified that both Ursula and Isabel were to take their new slave entourages and property and board the first boat for Portugal, where they were meant to support each other in their new lives.

A will is only effective if the courts enforce it. De Caminha was indisputably a man of wealth and influence, but he also must have known that his alliances with an ex-Jew and an African would not necessarily find a willing reception in the staid halls of Portuguese justice. We don’t know the fates of Ursula, Isabel, or de Caminha’s other slaves and concubines; it seems unlikely that they would have sailed to Lisbon, collected all that he had left to them, and then settled into Portuguese society as wealthy widows. In any case, his freewheeling sex life did not sit well with the Crown: It was after his death that the policy of appointing solid family men to high colonial posts was instituted.

5

On the other side of the Atlantic, the French in North America found that the more they blended with locals, the better it was for business. Early French colonists were dependent on the aboriginal peoples for their food supplies, as ships from home usually arrived late or came bearing spoiled food. Administrators were frequently forced to disperse their countrymen to local villages, as the resources of the settlements were insufficient to sustain them all. Once the colonists became accustomed to trapping and living with Native Americans, they often refused to work the land as their bosses wanted, preferring instead to conduct commerce with the tribes and hunt for a living.

Most Native Americans made no distinctions between the personal and professional, so sex and marriage often followed commercial relationships. French fur traders, for example, quickly recognized the advantages of forming close bonds with native women. Many kept wives or steady lovers in several locations, both for intimacy and to ensure a consistent supply of pelts. Rather than interdict such practices, French authorities sometimes tried to turn them to their advantage. By cautiously allowing the men to intermarry and produce children with Native Americans, they hoped to housebreak them. Marriage, they believed, would tame the French colonists’ fascination with “savage” life and guide them toward settling down and establishing profitable farms. In the process, they hoped that native women and their children would become Christians and eventually acquire the benefits of French civilization.

This “Frenchification” policy began in the 1660s and continued fitfully for several decades, but it ultimately failed. Rather than remaking aboriginal females into decent Frenchwomen, it was the men who went native. A 1709 letter from a Jesuit in Canada declared: “All the Frenchmen who have married Indian women have become libertines . . . [and] the children they have had are as idle as the Indians themselves; one must withhold permission for these sorts of marriages.” The rules then tightened, but relationships with natives and the men’s adoption of “lawlessness and idle” ways continued. The choice must have been easy for them. The allure of native women, freedom from repressive French authority, and profits from trading were all too strong to resist, regardless of whether or not they were approved back home. The French explorer Antoine de Lamothe, Sieur de Cadillac, wrote with disappointment in 1713 that his countrymen were “addicted to vice” with Native Americans, “whom they preferred to French women.” Worse, aboriginal women were inheriting their husbands’ wealth. In 1728, after complaints that native widows were returning to the wild with their dead husbands’ property, the law changed to disinherit them if they were to “return among the natives to live according to their manners.”

6