Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985-2010 (7 page)

Read Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985-2010 Online

Authors: Damien Broderick,Paul di Filippo

9

Joan Slonczewski

(1986)

BESIDES REPRODUCING

the evocative Ron Walotsky art from the first hardcover edition, the first paperback edition of Joan Slonczewski’s

A Door into Ocean

, from 1987, adds an interior illustration showing two darkly tinted naked humanoids amidst lush foliage and exotic flying and crawling beasts. A naïve reader today might easily mistake the scene for an outtake from the film

Avatar

, a project some twenty-plus years unborn when that paperback appeared. And thus we get a lesson yet again in how Hollywood “honors” its prose antecedents with outright shameless, unacknowledged theft.

And to compound the injustice, Slonczewski goes without fair credit for her influential, groundbreaking work even among hardcore readers. For although perceptive critics of the James Cameron movie cited many sf “contributions,” from Poul Anderson and Ursula K. Le Guin to the Strugatsky Brothers and Ben Bova, hardly any mention was made of Slonczewski’s important work, a finer accomplishment even than many of the other respected alleged sources, and one that stands to Cameron’s broad cartoony strokes as a Mary Cassatt painting to an animated advertising mascot.

Two contrasting worlds are intimately linked: Shora, a large moon, an ocean planet populated by parthenogenic females only, who rely on bio-sciences and possess a complex Zen-style philosophy of integration with nature and rules for harmonious interpersonal dynamics; and Valedon, the primary world, a planet hosting a warlike, competitive society of traditional males and females, who rely on the usual “hard” technologies, and who seem bent on despoiling Shora.

Two unofficial emissaries from Shora to Valedon adopt a young lad named Spinel and bring him back to their planet in an attempt to see if he may be “humanized.” A prior instance of such acculturation, a woman ambassador named Berenice, was a less-than-sufficient proof of concept—although she will continue to play an integral and touching role in the story.

Spinel adapts with no small reluctance and frequent misunderstandings, even falling in love and mating, tantric-sex-style, with Lystra (whose name, echoing the famous story of Lysistrata, is not be overlooked by the reader). After half a year on Shora, events compel Spinel’s return to Valedon, where culture shock with his old home further enlightens him. A campaign of brutal suppression is undertaken on Shora, and even Spinel’s return as interfacing man-of-two-worlds might be inadequate to secure peace.

The lucid gravitas of Slonczewski’s prose is matched by her even-handed comprehension of every viewpoint shared by her disparate cast, and her story—as well as her intricately fabricated ecology—contains numerous surprises and epiphanies, as well as plenty of Thoreauvian heartfelt paeans to the power of nature—a decided rarity in the “steel beach” catalogue of sf.

In the cool water, branch shadows wove fleeting patterns upon the hide of the young starworm. Lystra admired the sinuous trunk that stretched several swimming-lengths ahead of her, though barely a third as long as the maturer specimens of Raia-el. The mouth stalks of the starworm spread in a perfect star around its lip, none broken and regrown as on older starworms…. The young starworm had lone streamers of filters within its mouth, because it was not yet large enough to digest squid or large fish, only plankton and fingerlings. As Mithril’s cousins raked debris from the filters, Lystra swam up to the surface to get the net full of fingerlings that could be fed into the star-rimmed mouth, a handful at a time.

In the best manner of sf dialoguing, Slonczewski confesses to several inspirations, works she wished to respond to: Le Guin’s

The Word for the World is Forest

, Herbert’s

Dune

, and, surprisingly, Heinlein’s

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress

. She plucked from these models a set of polarities which she would embody in an alluring narrative, resolving their seeming incompatibility into a whole, organic synthesis.

Besides its generally acknowledged prominent place in the lineage of feminist sf,

A Door Into Ocean

fits neatly into three other equally valid traditions, conferring on it a quadrupled strength and complexity.

First is the utopian strain. Attempting to imagine and depict a society that confers maximum freedom and sustainable necessities for all, Slonczewski evokes any number of ancestors, from John Uri Lloyd’s

Etidorhpa

, through Le Guin’s

The Dispossessed

. And extending her influence forward, we reach descendants like Kim Stanley Robinson.

A second tributary of theme and topic might be deemed the literature of transcendental refusal, a much tinier stream in the canon than the utopia, but still significant. Melville’s

Bartleby, the Scrivener

and Edward Abbey’s

The Monkey Wrench Gang

come to mind.

Lastly, the third extra-feminist lineage shared by

Ocean

is the biopunk, or ribofunk one. Biology has always taken a back seat in sf to the so-called hard sciences, and works such as Damon Knight’s

Masters of Evolution

and T. J. Bass’s

The Godwhale

shine out all the more for their stance that squishy is powerful. Slonczewski’s training and expertise as a professor of biology lend her work a sophisticated plausibility and ingenuity found only at the top of this subgenre.

Feminist/monkey-wrenching/utopian/biopunk sf: now, that’s a standout combination that only a masterful writer could bring off! And Slonczewski does it superbly.

Slonczewski reportedly took eight years to craft

Ocean

, and her newest book (as of this essay) was separated from its predecessor by eleven years. But like the patient lifeshapers of Shora, what counts in her work is not speed and volume, but elegant living results.

10

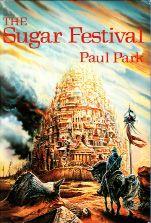

Paul Park

(1987)

[Starbridge Chronicles]

BRUCE STERLING,

Jeff VanderMeer, Paul Park: three authors who share a generation and who spent a sizable portion of their formative years outside the United States. For Sterling, India; for VanderMeer, Fiji; and for Park, Sri Lanka and other parts of Asia and Africa. The seminal experience of being indoctrinated in alienness and apartness shines forth in the writings of each, rendering them mutually resonant spirits, rare genre writers who have an interest in recreating the exotic, but inhabited from inside, with full understanding of the manifold traps and joys of multiculturalism. And certainly all three men share a kinship with older models of such genre cosmopolites: Cordwainer Smith (Paul Linebarger) and James Tiptree, Jr. (Alice Sheldon).

Park’s transcendent first novel,

Soldiers of Paradise

, and its sequels,

Sugar Rain

and

The Cult of Loving Kindness

, speak treasure troves about this kind of global upbringing and attitude, and certainly could not have been written with the same intensity, creative ferment and insightfulness by someone merely swotting up Baedekers.

Soldiers

and

Rain

are essentially one long narrative, broken in two for publishing purposes (and indeed they appeared yoked together in a second edition as The Sugar Festival), while Cult exhibits a time disjunction that qualifies it for separate inspection.

Initially our venue is the city of Charn and, later, its rival metropolis, Caladon. Charn is a big, dense, multiplex city of numerous well-delineated districts, inhabited by elites—primarily, the many-branched Starbridge family, with a distant member of the clan actually ruling Caladon as well—and masses of poor and suffering workers, some of them belonging to non-human races. With a complex topography—the major prison alone is an enormous labyrinth cored from a mountain and housing hundreds of thousands of prisoners—the religion-besotted, politics-mad, outré city is as much character as the major personages. The history and culture of this world—not Earth, but part of a solar system whose mechanics enforce seasons of enormous duration, seasons whose violent transitions power much of the disruptive human activity—are impasto’d with such intensity and specificity that Park’s world looms almost as solid as our own.

Those major protagonists would be Abu and Charity Starbridge, brother and sister, and their cousin, Doctor Thanakar. From a life of privilege, the three will descend into a welter of suffering as their city undergoes revolution and war. Martyred toward the end of the first volume, Abu becomes a saint whose legacy figures heavily in the third installment. The second book concerns the aftermath of the long war between Charn and Caladon, the French-Revolution-terror of the political scene in Charn, and the struggles of Thanakar and Charity to survive and reunite.

Park employs a certain distancing technique in his narrative, having our unnamed, omniscient historian sometimes speak of events as occupying the ancient past. But this occasional leap into historicity does not preclude an intense immediacy of sensory and emotional impact, as we follow Thanakar and Charity through their trials, to an eventual hard-won reunion of damaged souls.

In an interview with critic and editor Nick Gevers, Park said, “In the

Starbridge

books, the task I set for myself was to make a strange place come alive, so that the experience of reading it was comparable to the experience of living in that world. More than people or events, those books are about the place itself: to a large extent, especially in the first book, events occurred so as to carry the reader into different sections of the physical and social landscape. What I was trying to do was to make every moment both physically and emotionally vivid, which requires a lot of description, and a layered technique.” His success is undeniable.

The speculative elements in the sequence are integral to the human dramas, and innovative in their own right. The long seasons of this world, where a whole new generation may arise before, say, winter departs, have been integrated into the culture and internalized in the psyches of the inhabitants in curious and novel ways. Likewise the “sugar rain” of spring, with its mutation-inducing chemicals. And receiving insightful dissections are the power-trip strictures and habits of a religion whose actual epiphanies seems to be provable and irrefutable.

The third book inhabits a different but allied territory, being in some ways a pastorale opposed to the panoramic, Victor-Hugo-tapestried urbanism of the first two parts, almost a

Green Mansions

idyll. In a forest far from Charn, during the long summer that comes after the spring revolution, an elderly monk following quasi-Buddhist teachings and named Mr. Sarnath rescues two orphaned newborns, another brother and sister pairing, who grow up to be Rael and Cassia, teenaged acolytes of the Cult of Loving Kindness. Eventually Cassia becomes the prime engine of the movement.

Park’s close-up portrayal of this nascent crusade is almost Southern Gothic in its treatment. One could imagine this passage, for instance, to have come from Flannery O’Connor describing some backwoods revival meeting:

The cripple lay on his back, his long legs crossed, each ankle locked over the opposite knee. The two women were kneeling on either side of him. The piebald woman had unscrewed the top from a jar of ointment, and she was rubbing the ointment on the cripple’s legs. Still the crowd was singing and clapping to the rhythm that the pregnant woman had abandoned; she was out of breath. Her naked breasts were heaving as she bent down low and took some of the ointment on her palms.

This installment ends inconclusively, with Cassia’s legacy rippling forth unpredictably into the long, eternal future of the world.

Readers will search in vain for critical appreciation of the

Starbridge Chronicles

as part of the New Weird movement exemplified by China Miéville and others (Entry 62), but its place there is incontestable. Deriving much of its atmosphere, style, plot structures and characterization techniques from the work of Mervyn Peake, a New Weird preceptor, the

Starbridge Chronicles

serve as an interface between unchristened, older, proto-New Weird opuses such as Gene Wolfe’s

Book of the New Sun

and Robert Silverberg’s

Majipoor

sequence, and the younger novels that would finally crystallize the mode. Mention of the

Majipoor

books also brings up the much older subgenre of planetary romance, pioneered by Leigh Brackett and C. L. Moore, among others. The

Starbridge Chronicles

plays off this old pulp mode masterfully and with natural feel for

Planet Stories

exoticism. A savvy reader would not jump overmuch to encounter Moore’s hero Northwest Smith battling the insidious Shambleau in Charn’s precincts.

In the same conversation with Gevers cited earlier, Park self-deprecatingly observes, “The hardest thing for me as a writer is to speak without irony, without the protection of being misunderstood. To say, ‘this is what I think is important,’ or ‘this is what I think is true, or beautiful, or funny, or moving’—that is what is difficult for me.” But readers of this masterful series will attest that Park has brilliantly overcome any such earnest flubbing of his heart’s message.