Travels with Myself and Another

Read Travels with Myself and Another Online

Authors: Martha Gellhorn

Tags: #General, #Literary, #Travel, #Autobiography, #Editors, #Voyages And Travels, #Christian Personal Testimonies & Popular Inspirational Works, #Martha - Travel, #Women's Studies, #1908-, #Publishers, #Martha, #Journalists, #Gellhorn, #Women, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Personal Christian testimony & popular inspirational works, #Journalism, #Personal Memoirs, #Travel & holiday guides, #Biography And Autobiography, #Essays & Travelogues, #Martha - Prose & Criticism, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography

Most Tarcher/Putnam books are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchase for sales promotions, premiums, fund-raising, and educational needs.

Special books or book excerpts also can be created to fit specific needs. For details, write Putnam Special Markets, 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam

a member of

Penguin Putnam Inc.

375 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

www.penguinputnam.com

First published in 1978 by Eland

First Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam Edition 2001

Copyright © 1978 by Martha Gellhorn

Introduction copyright © 2001 by Bill Buford

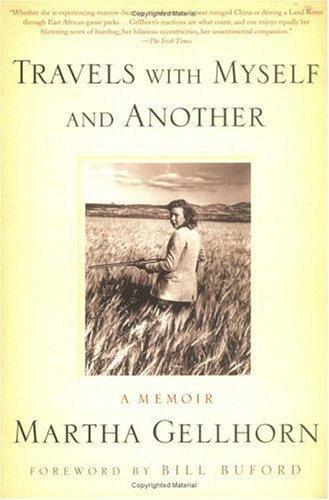

photo on page iv © Lloyd Arnold/Archive Photos, print courtesy of The John F. Kennedy Library; photo on page xxii by Ruth Rabb; photo on page 8 courtesy of The John F. Kennedy Library; photo on page 58 © U.S. Navy, courtesy of The John F. Kennedy Library; photo on page 106 by Ruth Rabb; photo on page 240 courtesy of The John F. Kennedy Library; photo on page 284 courtesy of The John F. Kennedy Library; photo on page 292 © Lloyd Arnold/Archive Photos, print courtesy of The John F. Kennedy Library

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not

be reproduced in any form without permission.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gellhorn, Martha, 1908-1998

Travels with myself and another / Martha Gellhorn.

p. cm.

Originally published: London: Allen Lane, 1978.

eISBN : 978-1-585-42090-2

By the same author

FICTION

The Trouble I’ve Seen

A Stricken Field

The Heart of Another

Liana

The Wine of Astonishment

The Honeyed Peace

Two by Two

His Own Man

Pretty Tales for Tired People

The Lowest Trees Have Tops

The Weather in Africa

NONFICTION

The Face of War

The View from the Ground

For Diana Cooper with long-lasting love

Idaho, 1940

The good traveller doesn’t know where he’s going.

The great traveller doesn’t know where he’s been.

CHUANG TZÛ

Leap before you look.

OLD SLAVONIC MAXIM

“Oh S. the sights are worse than the journeys.”

SYBILLE BEDFORD,

A VISIT TO DON OTAVIO

INTRODUCTION

My dear William. Note: that’s William. Not Bill. You must change your name. No one will ever take you seriously as Bill. Bill Buford? No, it just won’t do. And your hair. You’ve got to do something with your hair. And that beard? Shave it. You look like Allen Ginsberg.” I’m quoting Martha Gellhorn, a characteristic letter, imperious, forthright, even bullying. Martha was a novelist, a war correspondent and, with the publication of

Travels with Myself and Another

in 1978 (when she was just turning sixty), a travel writer of a wildly original voice. She died in 1998. I had the privilege of publishing some of her work during her last decade, her ninth.

“I forgot to add, William. You must buy new trousers that don’t look like what the well-dressed young elephants are wearing this year. How else can you win the Iranian’s love?” The Iranian in question was a particularly elusive girlfriend. Martha tutored me on matters of the heart, and on drinking (you could never drink enough), on my appearance (a disaster), and on my manners—especially my manners: my manners, in Martha’s eyes, were catastrophic.

“I’ll be in London for a few days later this month,” she wrote me after we had a row arising out of another one of my behavioral misdemeanors, and the exchange must have lead to Martha’s being so rude—and I infer this from the correspondence that I’m rereading for the first time—that I sank into a sulk.

“If you don’t return my call, I’ll sadly take it that you wish to sever relations forever. A pity. But think about it, William. I may be the only old person you know, and elders and betters are necessary as I know with despair, now that all of mine are dead.”

The elementary facts of her life: born in 1908, in St. Louis, the place, according to Martha, that everyone flees from (and thus the ideal nurturing ground for a travel writer); bossy, straight-talking, cigarette-smoking; the boozy reporter of wars and of the plight of the down-and-out; also a writer of short stories, novellas, and novels. She was married to Ernest Hemingway, and she hated the fact that, whenever her work was written about, his name was invariably mentioned as well, just as I’m mentioning it now. But it’s hard to avoid. The two of them met when the world was at its most dramatic. They fell in love at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War and divorced once World War II had ended—and in between was Cuba and big-game hunting and trips to China and battlefields in Finland and Barcelona and the beaches of Normandy. She rarely admits his existence, which makes his depiction here, in “Mr. Ma’s Tigers,” a great rarity. He’s the U.C. referred to, the Unwilling Companion (she wouldn’t, of course, use his name), and he comes across as a rascal of pranks and charm, held affectionately dear. It’s Martha, for instance, who insists that, despite Hemingway’s enthusiasm for Chinese fireworks, he simply has got to stop lighting them in the bedroom. Could there be any two people more romantic? By then he was Papa Hemingway, and she was, what, blonde and thin and sassy, a starlet of the highest order, a young Lauren Bacall, except that she was a whole lot brainier than a young Lauren Bacall, but just as sexy. There was a glamour about Martha Gellhorn, the glamour of black-and-white movies. It was in her manner and her way with the ways of the world. She was a dame.

In 1983, I hadn’t read Martha Gellhorn, but I was living in England and editing a literary magazine and putting together an issue of travel writing, and someone said I should ask her to contribute. I had missed the publication of

Travels with Myself and Another,

which appeared only five years before. I now believe I missed it because the book was written before its time (and therefore hadn’t fully caught on), even though most of the episodes described in it occurred many years before. Curiously, the book tells us as much about Gellhorn as the places she visits (curiously, because she was deeply private), and, in this, writing stories about journeys that are, finally, about many more things than the journeys themselves, she prefigures the works of people like Bruce Chatwin and Paul Theroux and Jonathan Raban and the renaissance of first-person adventure writing. I contacted Gellhorn—I got her address from someone—and a piece about a trip to Haiti was the result (something I only now recall had been originally intended for this volume but wasn’t finished in time). The piece was dramatic and eventful (a white woman on an island of angry blacks who nearly gets stoned) and full of what I would come to recognize as Gellhorn rage—the irrepressible, passionate rage against injustice. Gellhorn alludes to this rage in her account of visiting Mrs. Mandelstam (Mrs. M.), the widow of the great poet, one of the last and most moving essays in this volume. At some point, the famous widow describes living in constant fear, and she asks Martha if she, too, feels fear all the time. “No,” Martha says in reply (sharply, I imagine, definitively, without hesitation). “I feel angry. Every minute about everything.” No one was so capable of rage or of being so poetic expressing it.

“The Big Picture always exists,” she wrote, and by Big Picture she means the drama of power brokers and politicians and corporations. “And I seem to have spent my life observing how desperately the Big Picture affects the little people who did not devise it and have no control over it.” She was engaged by politics but hated politicians, and the ones who figure in this volume, like those who appeared throughout her life, are insufferably boring (and, in the Gellhorn vocabulary, there is no more damning thing to be). “I expected powerful political people to be boring,” she writes here, on meeting Chiang Kai-shek and his wife. “It comes from no one interrupting or arguing or telling them to shut up. The more powerful the more boring.” Politics, she declares during her trip across the equator of Africa (she had never been; it seemed like a journey worth taking; why not?), is the bungling management of the affairs of men. “It is a game played among themselves by a breed of professionals. What has politics to do with real daily life, as real people live it?”

I was astonished by Gellhorn when I finally met her. I felt I had discovered her and didn’t know why it had taken me so long. This American in Britain, this throwback to a time when truth was truth, and right was right, and wrong was an identifiable thing that must be fought at all costs—she was all these things, and I fell for her. I wanted to do everything for her. I wanted to publish her in my magazine. I wanted to publish her books. I wanted to be her agent. I wanted to see her work translated, brought back into print, made into movies. And, for a brief period (both of us fools), she let me be all these things—editor, publisher, agent, the works. But I was still in my twenties and briefly believed that there was nothing I couldn’t do, and she, nearly fifty years older, probably should have known better. I know now that I had put myself in a role that she was already familiar with: the incompetent male charmer whom she had to tell what to do and how to do it. I had chills of recognition rereading Martha’s account of travelling across East Africa, with a driver, Joshua, who knew neither East Africa nor how to drive. (And only Martha would end up with a driver who can’t drive and then go on to spend more time with him than any other travelling companion in her life.) On meeting Joshua (“black imitation Italian silk pipestream trousers, white shirt, black pointed shoes, black sunglasses in ornate red frames, holding a cardboard suitcase”), Martha knew he was probably not right. “Instinct, which I regularly ignore, told me that Joshua was not the man for the job.” Instinct told her, I’m sure, that I was not the man for the job as well, but we carried on until it became too obvious to ignore.

Her letters to me are postmarked Belize and Kenya and Tanzania and the south of Spain. Martha was fundamentally a loner (in this volume, you’ll note that people are rude, incompetent, unreliable, drunk, and they smell very bad; Martha never travelled for people; it was natural beauty she sought, the view of the Rift Valley, a beach on the Indian Ocean, a giraffe in the wild). Her social life, true to character, was conducted mainly through letters, written late at night, in solitude, and these stories were often first told in letters home—letters that Martha recovered in order to write this book.

She was happiest in places hot enough that she could wear little—she lived for swimming—but her home was a cottage in north Wales, Catscradle, atop a blustery, exposed hill (again, every travel writer needs a place from which to flee), where she lived alone, drank booze, read mystery novels, and wrote, until she got tired of her company and came into London. Her days there were tightly organized—drinks and dinners and maybe a nightcap. She didn’t have parties—she rarely saw people in groups—but met with her friends, one by one. John Pilger, Paul Theroux, James Fox, Nicholas Shakespeare, John Hatt, Jeremy Harding—journalists, adventurers. Those were some of her regular men friends. We’d see each other—one of us on the way out, while another was arriving. She had some women friends, but Martha liked men, was easy around them, and could be flirty and coquettish even at the age of eight-five. One evening, she recounted her being thrown off a press boat during the Normandy invasion (Hemingway, with whom she was by then in a relationship of unmitigated acrimony, had taken her credentials), and her being summarily returned to Britain. By her own account, she flirted her way back onto another boat (a hospital ship), stowed away in a broom closet, and saw the invasion firsthand. It was a telling incident: unintimidated by one of the most dangerous military operations of the war (and so fearless in a male way) and yet utterly capable of making men melt (devastating in her distinctly female way). And of course Hemingway.

I brought him up the first time I went to her London flat for dinner. It was the forbidden subject. “William,” she said, “I have only one response to people when they bring up his name. And that’s to show them the door.” She didn’t show me the door. In fact, the taboo having been broken, she went on to talk about him at length—both that evening and on many occasions thereafter. Yes, she resented him for all kinds of reasons, but he was the only man she talked about. She mentioned her next husband only once—that was Thomas Matthews, the editor of

Time

magazine—and that was to express her regret at having been married to the man. “I don’t know what happened,” she said. “It’s as if, for ten years, I just stopped thinking. I did no work. I did no writing. Just endless entertaining—grand dinners with crystal and china and men in dinner jackets serving us.”

But Hemingway was present on a first-name basis. Sometimes it was Ernest the monster (how he terrified his children) and sometimes Ernest the myth (he was, in her words, “shy in bed,” and had, she was convinced, slept with no more than five women). She was fed up with him by the end of World War II—he was bloated and self-centered and indifferent to history—but she had respect for the writing. She talked about the philosophy of his sentences and that business of paring them back until they were as direct and true as they could possibly be—something she did herself in her own, tough, often staccato prose, one that often hangs on one perfectly chosen word, usually a simile: the flamingoes, in East Africa, lifting off and spreading in a coral pink streamer against the sky, and “the sound of flight was like silk tearing.” Mr. Slicker, another one of Martha’s wholly inappropriate guides, tells Martha how the locals value the texture of skin in a woman—this is the quality they find beautiful—and Martha understands why, “since the ladies were mainly huge bottoms, like carrying your own pillow.”

These are very Gellhorn sentences—careful, witty, spare. On our many, always boozy nights together, she talked like this and said many more things, vivid and indiscreet at the time, but usually uttered under the influence of her liquor cabinet or the bottles of wine that we had at dinner (“tight as a tick” was one of her phrases), and few details now remain. Once I recall writing something down on a napkin—Martha had gone to the loo, having just revealed some wonderfully salacious anecdote—but I was myself so drunk that I later blew my nose into it and then threw it away.

There was a growing suspicion among Martha’s friends that she would never die. She had too much energy, too much determination to be curtailed by something as ordinary as mortality. She had a ninetieth birthday coming up. Surely she’d make that. And there was the prospect of another war, in Iraq, in the Balkans—Martha wouldn’t allow herself to miss those. But she will. And she did.

I feel lucky to have known her, this proof of the human spirit, the naysayer to naysayers. I know her friends do, too. Now we just have her books. And, among my favorites is this one,

Travels with Myself and Another,

in part because it’s her most revealing book, the closest thing we’ll get to an autobiography. It’s also one of her most forthright—energetic, vicious, self-deprecating, bigoted, witty, and outrageous. It’s very Gellhorn.

—

Bill (“William”) Buford