Scent and Subversion (14 page)

Read Scent and Subversion Online

Authors: Barbara Herman

by Christian Dior (1949)

Perfumer:

Edmond Roudnitska

A cross between Roudnitska’s fruity chypre Femme (in its Prunol buttery plumminess) and Guerlain’s Mitsouko, Diorama might challenge fans of angular minimalism. Its combination of fruity, spicy, and powdery just might be too much. Jean-Claude Ellena, the pope of minimalism himself, declared himself a fan: “No perfume has ever had a

more complex form and formula, more feminine contours, or been more sensual, more carnal.”

Top notes:

Bergamot, aldehydes

Heart notes:

Jasmine, rose, gardenia, peach and plum (undecalactone gamma—peach aldehyde—and Prunol), raspberry, strawberry, galbanum, lily of the valley

Base notes:

Patchouli, oakmoss, vetiver, violet (methyl ionone gamma), labdanum, castoreum, civet

by MEM Company (1949)

A friendly, unassuming leather-and-woods scent that smells like it was meant to be splashed on as an aftershave, English Leather balances a leather base with honeyed rose heart and a fresh, herbaceous top. Tonka’s cinnamony-vanilla provides a slightly sweet warmth in the drydown.

Top notes:

Bergamot, lemon, petit grain, orange, lavender, rosemary

Heart notes:

Rose, orris, honey, fern

Base notes:

Cedarwood, leather, tonka, vetiver, musk

(La Fuite des Heures) by Balenciaga (1949)

Perfumer:

Germaine Cellier

Has the name for a perfume ever so aptly described the quality all perfumes share? Namely, that poetic condition of being something beautiful and rare yet momentary—evaporated almost as soon as we have contact with it.

Fleeting, too, are the notes that make up the perfume. It is hard to tell what exactly I smelled when I first took a whiff. Soapy and aldehydic, but with a soft, organic, herbal base that smelled like nature refracted through synthetics, helping to blend, soften, and blur the recognizable lines of the flowers and herbs.

Fleeting Moment reminds me of the perfume version of a now-discontinued (of course!) drink from the UK I used to splurge on, called Aqua Libra. This lightly carbonated and ever so delicately sweet drink was infused with herbs: tarragon, cardamom, thyme, sesame seeds. It was so interesting I felt like I was drinking perfume.

Top notes:

Citrus aldehydic with a slightly aromatic touch (tarragon-like): bergamot, orange, aldehyde C10, aldehyde C11-enique, neroli

Heart notes:

Floral bouquet (ylang-ylang, fresh rose, jasmine) with a very light lily-of-the-valley base (more modern than No. 5), and floral powdery notes (orris absolute and methyl ionones)

Base notes:

Soft woody with powdery and musky notes like vetiver (plus the acetate), sandalwood, vanilla, sweet coumarine, and musk (musk ketone and natural musk)

(Notes from Octavian Coifan.)

by Coty (1949)

In the running now as one of my favorite vintage tuberose perfumes, Méteor certainly rocketed into my stratosphere and took me by surprise. Buttery tuberose joins with jasmine and rose to attack on one side while civet and nitromusks get you from the other. It’s an effective little formula, this My Sin–esque combo of sexy florals plus animal notes. Sumptuous and hard to find.

Notes:

Jasmine, rose, tuberose, musk, civet

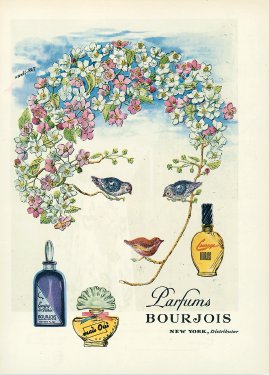

In this 1940s ad by artist Xanti-Pat, three birds make up the

trompe l’oeil

eyes and mouth of this lovely woman for Bourjois perfumes.

Before Demeter perfumes created Gin and Tonic and Cosmopolitan, Jean Patou had cocktail-scented perfumes. In addition to Dry, featured in this 1952 ad for the 1930s-era perfume by artist Maynard, there was the original Cocktail and Bitter Sweet.

Intimate, Cabochard, Youth Dew (1950–1959)

I

n the 1950s, perfume was all about “friendly-sexy.” If aggressive 1980s perfumes wore olfactory shoulder pads, as perfume writer Susan Irvine suggests in her book,

Perfume Guide,

then picture 1950s perfumes wearing those dresses with rounded shoulders and poofy skirts. “Friendly-sexy” was exemplified by Marilyn Monroe’s soft, downward-curving, and rounded eyes, full lips, and pillowy body. Her look screamed sex—but with a smile.

Perfume in the 1950s, represented by Revlon’s Intimate or Robert Piguet’s Baghari, is also steeped in musky sensuality. Intimate’s animalic ballast—castoreum, civet, and musk—is about as subtle as a bullet bra, and Baghari sinks you into a musky vanilla reverie that is heavy and rich. The good girl / bad girl dichotomy was in rare form in 1950s perfumes, exemplified in the Max Factor ad for Primitif, which asks the question, “Why not let your perfume say the things you would not dare to?” Poivre by Caron reminds us that not all 1950s perfumes were addressing the women who would be Marilyn; with its aggressive pepper and clove notes, one is reminded that Sylvia Plath, Diane Arbus, and Anne Sexton inhabited—and set fire to—that decade as well.

by Robert Piguet (1950)

Perfumer:

Francis Fabron

The mark of a beautiful perfume is that even though it may not be your type, it pulls you in anyway. Such is the power of Baghari. Soft, floral, even tropical, Baghari has a lushness, like fur, that has to be experienced to be understood. It smells like fur scented with flowers—animalic and sophisticated yet unintimidating.

Baghari was the first vintage perfume that showed me that vintage perfumes can have a depth—a volume, as some people say—a way of unfolding through time that even complex, modern fragrances don’t have. Baghari’s appeal was its roundness, for lack of a better word, something 3-D and physical about it that I haven’t really encountered in any modern fragrances.

I gave perfumer Yann Vasnier a sample of Baghari, and he smelled aldehydes; orange flower; orris; jasmine; rose; clove; hay; musk; and Animalis, a perfume base by Synarome that contains civet, castoreum, musk, and perhaps costus. Thanks to the depth and boozy richness that come from its animal base, Baghari, like vintage Chanel No. 5, is practically a touchstone for animalic perfumes.

Top notes:

Aldehydes, bergamot, orange blossom, lemon

Heart notes:

Rose, lilac, ylang-ylang, lily of the valley, jasmine, bourbon vetiver

Base notes:

Benzoin, musk, amber, vanilla

(Thanks to Denyse Beaulieu of the blog Grain de Musc for the information on Animalis.)

(1951)

Perfumer:

Edmond Roudnitska

Perfumer Edmond Roudnitska said of Eau d’Hermès that it was “the interior of a Hermès bag in which wafted the aroma of a perfume … A note of fine leather, wrapped in a slightly spicy citrus.” And actual wearers of the stuff? “Sweaty balls may be the most accurate description of the scent,” writes one irreverent wag on a perfume forum.

My first impression was somewhere between the haute leather impregnated with spicy citrus and abject bodily smells: I smelled cuminy lemon with a dose of animalic civet, backed up by herbs and spices such as lavender, clove cinnamon, and coriander. Clean shot through with something not exactly dirty, but rather, alive. (Cumin is not listed in the official notes, but it’s unmistakably present.)

Notes:

Lavender, lemon, clove, cardamom, cinnamon, coriander, geranium leaf

by Caron (1951)

In this 1955 ad for Caron’s Poivre (“Pepper”), a red dragon wrapped around the Caron bottle evokes China and the spice trade. The eau de toilette version, Coup de Fouet (“Crack of the Whip”), is lighter, but still spicy.

Perfumer:

Michel Morsetti

Many fragrances from the 1950s helped women to express their erotic selves through carnal, animalic perfume notes, or, as the Max Factor Primitif ad put it, these perfumes helped “say the things” that women “would not dare to.” But this is a familiar trope in perfume. Sniffing Caron’s Poivre and thinking about all the metaphors of fire and explosives in its ads and descriptions, I began thinking about how many perfumes express violence and danger in their notes, perfume signifiers not entirely subsumed by sexuality?

Well, Caron’s Poivre, for one. Apparently, Caron’s creative director Félicie Wanpouille, who had collaborated with Caron perfumer Ernest Daltroff on the drop-dead sexy Narcisse Noir, wanted to buck the trend of 1950s well-mannered, ladylike florals, so she asked Caron’s then-perfumer Michel Morsetti to create something fierce and wild.

Caron’s Poivre extrait starts off with a fiery and earthy spark of crushed black pepper and sharp florals (you really smell the ylang-ylang). Then, like a slow-motion olfactive explosion, it unfurls carnation’s clovey facets, weaving together floral and spice, with sweet warmth from clove and opopanax. To add fuel to the fire, so to speak, it turns out that pepper is not the only note that signifies darkness and danger in Poivre: There’s also carnation. Not only has the American carnation largely lost its characteristic spicy smell, but it also appears that we don’t have the dark associations with carnations/cloves that Europeans do. In France, for example, cloves have been considered bad luck for centuries.

Notes:

Red and black pepper, clove, carnation, ylang-ylang, jasmine, opopanax, cedar, sandalwood, vetiver, oakmoss, musk

by Nina Ricci (1952)

Perfumers:

Michel Hy and Jacques Bercia

The word

animalic

as a perfume descriptor refers to base notes sourced from animal bodies—civet, castoreum, and musk, for example. But sometimes, plant-derived ingredients such as costus root, the dried root of the

Saussurea lappa,

can also provide the eros and warmth that evokes the human animal.

Fille d’Ève (“Eve’s Daughter”) starts off very brightly, with an herby, citrusy, sweet floral note that is sparkling and feminine. The perfume exists for me in the drydown, when the costus root note rises up like the bed-head scent of a well-washed beauty on her third day without bathing. According to perfume historian Octavian Coifan, costus root references sebum, the smell of dirty hair, and it has a “slightly resinic note, like myrrh, elemi or opopanax.” If you have, as I do, a fetish for hair that smells slightly dirty and greasy—particularly if you can still smell traces of the shampoo from the last wash—then Fille d’Ève is for you.

As the clean, white flowers fade, the velvety sebum takes over, and Fille d’Ève becomes a gorgeous skin scent, a scent someone would have to lean in close to get a whiff of. There’s something very sexy to me about the idea that you’d wear a perfume not to mask your own gorgeous dirty smells with aldehydic flowers, but to enhance them.

The

1964 Dictionnaire des Parfums de France

describes Fille d’Ève as “An original chypre subdued by fruity notes … an endearing fragrance combining freshness and seduction.”

Notes from

1964 Dictionnaire des Parfums de France:

Oak absolute, jasmine, bouvardia, cistus, bergamot, clove, patchouli, pinang

by Galion (1952)

The rose in Snob is raised an octave by green narcissus, light hyacinth, and a tuberose/jasmine duo that injects Snob with an oomph that momentarily quotes the perfume Joy’s richness. Maybe Snob is Joy’s nouveau riche cousin who’s bragging about being related to Joy? Whatever the case, there’s a family resemblance—and it’s intoxicatingly beautiful. The

1964 Dictionnaire des Parfums de France

describes Snob as “a floral aldehyde … [i]deal for society events, cruises and sunny days.”

Notes from

1964 Dictionnaire des Parfums de France:

Aldehydes, narcissus, hyacinth, rose, jasmine, tuberose

by Estée Lauder (1952)

Perfumer:

Josephine Catapano with Ernest Shiftan

Neither youthful nor dewy, Estée Lauder’s first fragrance, Youth Dew, was initially marketed as a scented bath oil so that women would buy it for themselves. (Men were supposed to buy women perfume and jewlery.) I know it’s a beautifully composed fragrance, and I can even appreciate its beauty in a technical, cerebral way. But its sweet, amber/vanillic heaviness and mossy-spicy-bitter herbaceousness are two great tastes that for me, anyway, don’t taste great together. Hours into it, though, the drydown is fantastic—soft, a little funky, and ambery warm.

Top notes:

Orange, spice note, bergamot, peach, aldehydes

Heart notes:

Clove, rose, ylang-ylang, cinnamon, cassie, jasmine, orchid

Base notes:

Amber, tolu, patchouli, olibanum, oakmoss, Peru balsam, benzoin, vanilla

by Christian Dior (1953)

Perfumer:

Edmond Roudnitska

A simple, herbal/anisic chypre that Edmond Roudnitska described at the time as “the only true chypre on the market.” To a modern nose, it might come across as a little too lemony.

Top notes:

Mandarin, orange, lemon

Heart notes:

Rosewood

Base notes:

Vanilla, oak moss

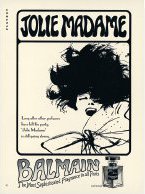

by Pierre Balmain (1953)

This elegant 1950s leather chypre is advertised as a party-girl fragrance … in

Playboy

.

Perfumer:

Germaine Cellier

Perfumer Germaine Cellier often played with olfactory gender conventions in her perfumes, femme-ing up Fracas into a floral so over-the-top it was almost a parody of a feminine fragrance (or at least its campy version), and butching up Bandit into a green leather chypre with a buzz cut and a leather jacket.

In Jolie Madame, masculine and feminine notes coexist in contrast without ever resolving themselves, exposing how arbitrary gender in perfume is, and perhaps also reflecting how complex gender codes were for the 1950s woman.The almost cloying floral notes are undercut with the tough notes of leather, musk, castoreum, and civet, demonstrating in perfume form that a ’50s woman may have appeared all smiles and pleasantness, but underneath she could be the toughest person around, or, to be less literal, more complex than those florals would suggest.

Top notes:

Gardenia, artemisia, bergamot, coriander, neroli

Heart notes:

Jasmine, tuberose, rose, orris, jonquil

Base notes:

Patchouli, oakmoss, vetiver, musk, castoreum, leather, civet

by Dana (1955)

If 1940s and ’50s perfume ads are any indication, trapping—or in this case, Ambushing—a man was a full-time job. Perfume, as shown here, is apparently one of a woman’s man-trapping tools.