Scent and Subversion (11 page)

Read Scent and Subversion Online

Authors: Barbara Herman

It’s hard to imagine perfume brands today getting away with using wartime themes as part of their advertising campaigns, but Corday did it in this 1940s ad.

Vent Vert, Femme, Miss Dior (1940–1949)

W

ith the darkness of World War II dominating the first half of the decade, it’s not a surprise that renewal and rebirth in perfumery, in the olfactory form of green scents, would help to represent the reinvigoration of a world in disarray. And no perfumer dominated the 1940s in the way that iconoclast Germaine Cellier did, almost single-handedly jump-starting perfume with adrenaline shots to its olfactory heart with a dizzying array of scents, including Bandit (1944), Coeur-Joie (1946), the galbanum-overdosed Vent Vert (1947), Fracas (1948), and Fleeting Moment (1949).

Some women had to play dual roles in the 1940s—working outside of the home when men were off to war, but then returning to a traditional kind of femininity in the home when they came back. Christian Dior’s New Look in 1947 responded to their homecoming/traditional role with fashion’s return, as has been said, to a kind of Belle Époque femininity: full skirts, soft shoulders, and cinched-in waists. Cellier, one of the few female perfumers of that time, created scents that reflected an awareness of the multiple roles women were supposed to play in the 1940s and scents that seemed to question the idea of gender itself. If one looks at her fragrances from this perspective, their wildly gender-bending ways make historical sense: From the butch, leather-clad masculinity of Bandit to its counterpart, the aggressive, almost-drag femininity of Fracas, these perfumes suggest that gender is something constructed, as arbitrary and labile as a perfume one could put on or take off.

by Dana (1940)

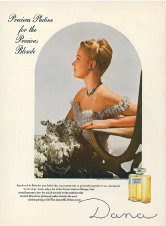

“For the precious blonde,” Platine perfume had silver flecks floating in it like confetti, and its ads were often co-branded with jewelers, such as this one from 1944, with Harry Winston.

A fresh floral aldehydic chypre on the green lily of the valley side, Platine (or “Platinum”) was marketed “for the precious blonde,” complete with platinum flecks floating in its Art Deco bottle. In ads, the platinum blonde woman who was its namesake seemed remote, untouchable, and unreal. Its freshness, perhaps due to vetiver and sandalwood, is much more soft, friendly, and approachable.

Notes not available

.

by Lucien Lelong (1940)

Perfumer:

Jean Carles

A perfume name that matches its character, Jean Carles’s whimsical Tailspin sends you careening and spinning from one incongruous perfume accord to the next, making your olfactory brain work overtime trying to figure out what’s going on. It starts out with an herbal, vegetal green freshness with minimal sweetness, moves to a rich floral that’s hard to identify, then to a tobacco-y, cinnamon spice base that resolves into a soapy floral. Its cinnamon spice seems very Carles-like, like the marriage of cinnamon with gardenia in Carles’s Ma Griffe. The jarring and odd part of Tailspin is a confusing, coal-tar aspect that disappears as quickly as it arrives.

Notes not available.

by Houbigant (1941)

In the same way that some perfumes smell insurmountably gendered, some notes smell resolutely old-fashioned; for example, the “powderiness” that sometimes comes from carnation, orris, and sandalwood, all three of which are in Chantilly. If you can get past this modern prejudice against powdery scents, Chantilly will knock your socks off. If you can’t, spicy baby powder will be all you can smell, which would be a pity.

Chantilly starts off with fresh lemony/fruit top notes, evolving into a powdery, spicy floral with flashes of animalic leather and musk. It’s hard to discern specific floral notes, although the carnation’s spice builds a bridge to its rich undertow of sandalwood, and rich balsams. A classical powdery Oriental that smells old-fashioned in one sense and sexy-animalic in another. If you can handle the dichotomy, you’ll love Chantilly.

Top notes:

Bergamot, lemon, neroli, fruit note

Heart notes:

Jasmine, rose, ylang-ylang, carnation, orris

Base notes:

Sandalwood, vanilla, leather, benzoin, tonka, musk

by Robert Piguet (1944)

A bottle of Bandit perfume pierced and shattered by a dagger evokes the perfume’s provocative scent and shocking debut on the designer’s catwalk in this 1947 advertisement.

Perfumer:

Germaine Cellier

Perfumer Germaine Cellier was said to have been inspired to create Bandit when she took a whiff of models changing their undergarments backstage at a Robert Piguet show. In a fitting debut for the perfume, models dressed as pirates, complete with masks, toy guns, and knives, introduced Bandit to the public during a Robert Piguet fashion show. Lore has it that one model smashed a bottle of Bandit on the runway, turning on her heels as the bitter, gorgeous, butch perfume filled the air.

So does this bitter, smoky, leather chypre live up to its myth?

Yes.

Its dominant twin notes—the sting of galbanum with the warmth of leather—encircle any sweetness that could emerge from jasmine or rose. Although Haarmann & Reimer’s perfume notes listed below don’t include isobutyl quinoline (a synthetic leather note that often smells rubbery and bitter), it was Cellier’s daring 1 percent overdose of that ingredient that makes it infamous. Galbanum and isobutyl quinoline make Bandit an extreme scent: Picture a bouquet of flowers wrapped with a black whip instead of a shiny ribbon.

Bandit’s sharp angles make you pause and think. Its cacophonous notes are at the core of its appeal, like an instrument playing off-key in an atonal modern musical

composition, or a modernist portrait of a woman with a blue face and green lips. Dry, leathery, mossy—call it what you will, but Bandit makes being bad smell good.

Top notes:

Artemisia, bergamot, gardenia, aldehydes, galbanum

Heart notes:

Jasmine, orris, rose, carnation

Base notes:

Castoreum, patchouli, vetiver, myrrh, oak moss, amber, civet

by Rochas (1944)

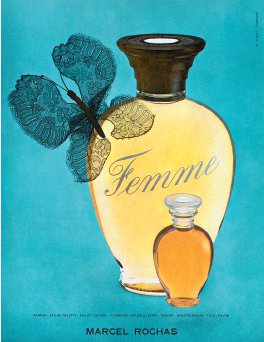

This 1957 ad for Femme by Rochas features the curvy bottle inspired by Mae West’s hourglass figure.

Perfumer:

Edmond Roudnitska

Like the inside of a woman’s butter-soft suede purse that has accumulated the feminine smells of perfume, lipstick, and other womanly objects, this classic fruit chypre smells like softness. Roudnitska created Femme in 1944 for Marcel Rochas to give to his wife, and the bottle was designed to recall Mae West’s hourglass figure. Its reformulated versions with cumin seem more wearable and modern.

Top notes:

Peach, plum, lemon

Heart notes:

Jasmine, rose, rosewood

Base notes:

Patchouli, musk, amber, civet, leather, oakmoss, sandalwood

by Raphael (1944)

Réplique smells like a lot of good ideas thrown together that just don’t add up.

It first challenges you with its herbaceous top note—sweet, citrusy qualities—followed by its spicy, animalic, almost gourmand base. This complex, overloaded Oriental perfume smells sickly sweet and uncomfortably creamy in the drydown. To me, it’s this herbaceous green quality that throws me off, creating a difficult minor-key element to an already dark-toned perfume.

If Réplique were a drink, it would be Fernet Branca, a mix of herbs, vanilla, and orange in a dark iteration. Was it inspired by Tabu, and a precursor to Opium, Obsession, Youth Dew, and other big-bosomed perfumes? Once it settles down, the drydown gets sexier and more tolerable—a dark Vermeer painting of a perfume.

Top notes:

Bergamot, neroli, orange, coriander, clary sage

Heart notes:

Clove bud, rose, orris, ylang-ylang, jasmine, tuberose

Base notes:

Patchouli, amber, moss, leather, musk, vanilla, civet

by Fabergé (1944)

In spite of being advertised as a scent “for the casual you,” the spicy, vanillic, and animalic Woodhue has a darker, more-mysterious vibe than its ad would suggest. As often happens with vintage perfume, Woodhue’s top notes were a bit off the first time I sniffed it, and in this case, initially smelled like hairspray.

Woodhue was most seductive when it was in the last stages of the drydown. A delicate, orris-like veil of powdery softness blended with the spices, vanilla, and touch of civety musk. Perfume historian Octavian Coifan sees Woodhue as built around a floral spicy note that sits between the “fresh rose facet of Chanel No. 5 and the soft, sweet, spicy carnation of L’Air du Temps.”

An hour or so in, a natural vanilla scent blended in with my skin to create a comforting, ambrosial, lightly sweetened milkiness. Occasionally, sniffing my wrist with my nose up close to my skin, jasmine would pierce through the softness like rays of sunshine through a cloud. The rocky road to this drydown is worth it, so if you get some of the old stuff, give it a chance to sputter, screech, and blow smoke like an old jalopy you started up after fifty years of its lying inert. It’ll be worth it once this scent hits its stride, and the resulting ride is smooth.

Notes from

Octavian Coifan:

Jasmine, ylang-ylang, orris, clove, a green violet note, methyl ionone, ionones, benzoin, vanilla, opopanax, myrrh, amber accord, nitromusks, civet, sandalwood, cedar, vetiver

by Weil (1945)

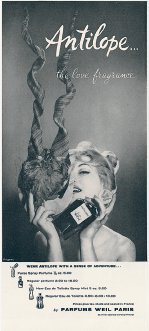

Is the woman who holds up antelope antlers and a bottle of Antilope perfume supposed to be hunter or prey?

You’d think that a perfume called Antilope would be a little more, well, gamey or animalic, but Antilope by Weil lives up more to the habitat of the antelope than to the animal the name evokes. One gets the sense that the leaves, woods, and flowers that went into Antilope have dried into a haylike concentration whose scent is stirred into recognition only by a hot sun or a brief summer wind. I imagine a sleeping animal on a bed of herbs, dried grass with flowers in the distance. In sum: dry, sweet, and woody.

Top notes:

Aldehydes, spice note, citrus oils

Heart notes:

Jasmine, rose, orris, lily of the valley, violet

Base notes:

Cedarwood, vetiver, leather, musk, amber

Notes from

PerfumeIntelligence.co.uk:

Tangerine, neroli, galbanum, acacia, farnesiana, narcissus, hyacinth, ylang-ylang, may rose, lily of the valley, oakmoss, civet, sandalwood, and musk