Save the Cat! Strikes Back: More Trouble For... (16 page)

Read Save the Cat! Strikes Back: More Trouble For... Online

Authors: Blake Snyder

Tags: #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #Screenwriting

As the writer, in addition to getting notes on every page that needs fixing — little things mostly — you must decipher what the main problems are by making sure you understand what is required. At every step of the way, as Dean points out, execs may have different, even contradictory, opinions. That's fine. Nobody's perfect. We're all searching for the solution here and circling the answer isn't an exact science (although using

Save the Cat!

comes close). But since “you're the writer,” it's up to you to “get it.” If you don't understand, get clarification before starting. If a note is contradictory, without playing “Gotcha!” say so, but only in trying to be clear about what's being asked.

There will sometimes be tension. And the more tension, the more difficult it is to hear notes on your script without having one of two reactions: “I suck” or “You suck,” when in truth neither is correct. I have been in meetings, both as the writer and as the producer, when a note is given that a writer disagrees with, resulting in a quite obvious “bile-rising clenching of the teeth,” that instant where we all go:

Uh-oh

.

The truth is if you didn't have passion for a project, you would be worth nothing. Studios don't want zombie note takers, but they don't want hair-trigger bomb throwers either. Yet it all starts with that moment in the meeting when someone broaches a subject that the writer does not look happy about. You wanted to call a character Minnie in honor of your favorite grandmother, and the note is: “Kill Minnie.” Or worse: “Can we change Minnie's name? She sounds like a mouse.” Little darlings like these are dropping left and right, and that's just the warm-up. The whole reason for writing this script is the theme you struggled to build into every scene — “No man is an island” — to which everyone says: “Can we lose the maudlin stuff?”

This is not the theater where the writer's power is supreme; this is not even publishing, where you own the copyright. This is da movies. And in some cases, you are now a hired gun assigned to kill someone you love very much: you. Dan has great advice:

Don't be defensive. I know you've worked months on every word and scene, but the meeting with the producers has to be open-minded about the project as a whole. This is tough, but if you are defending every note, not only will it wear the producers down and make them more reluctant to be even more direct about their feelings, but you won't get a clear picture of their thoughts.

And that is really the job!

But I do have some good news: The more you do this, the easier it becomes — especially after you learn to be open to suggestions. I often think about something that happened years ago with a pair of writers I worked with. Now a successful team, at the time they were young and still finding their stride. On this particular project, we had to deal with several rounds of notes from producers and the team's attitude was unreceptive. The producers were afraid the writers weren't up to the task, and because I was the intermediary, it was my duty to lower the boom. I felt it was not only a defining moment in the project, but in their careers, and told them so, yet had little confidence they heard me.

But at the next meeting, it was like a switch was flipped. The producers’ notes were comprehensive, yet the duo didn't hesitate. They went into the rewrite with gusto, and projected the attitude they could be back tomorrow, throw that script out, and start over with even better stuff. The project survived, but more important, I'll always think of it as the moment they turned pro.

To quote Dan:

Don't be afraid to try sweeping changes. You've always got the first draft to fall back on if the second turns out to be too extreme. I can't tell you how many times I've received a second draft where the writer goes on and on about all the changes that were made, only to find that minimal things were done — a few scenes moved around, a character's name changed, what-ever. Again, don't be afraid to rewrite stuff, or at least explore big dramatic changes. At least for a day or two.

And I couldn't agree more.

You've heard “writing is rewriting”? Ha! This is child's play compared to the true “

reeee-eee

-writing” we are often called on to perform as screenwriters at the behest of those we've been hired by. And the pros, the winners, the A-listers… don't whine. They just do it. The shooting script for

Little Miss Sunshine

was number 100 according to its author, Michael Arndt. Even in my own experience with

Blank Check

, a movie Colby Carr and I wrote in March of 1993 and was out in theaters by February 1994 (under a year), we had 20 to 30 drafts to get it into shape by first day of shooting, including working through drafts from other writers who had been hired (unbeknownst to us) by the studio. And yet we kept managing to put it back right — and kept improving it, too.

Point is, let go. Get over yourself. You'll always have Paris and that first draft, but if you want to get into production, you have to let those who are responsible for the finances see all the extrapolations of your story they want to. They want the “hero-is-a-teenager” draft when, in fact, the hero in your script is 30 years old? You will try like hell to talk them out of it. But “at the end of the day,” it's their dime. To quote Jeremy on this subject:

Know what fights to fight and when to lay down. If you're 100% sure you are right, fight the fight. If not, then try with your best efforts and who knows, maybe the guy is a big-time producer because he's not such an idiot after all. I've been certain that I was correct about something until I tried it differently and it was better!

Weaving your way through the rewrite process is about hearing notes and delivering script improvements to the best of your ability. Often this involves “interpolating” to get to the “real note,” which can drive writers batty. Yet we must abide.

Once, Colby Carr and I got the feedback that we should make our script “25% funnier.” Excuse me? Let me get my Gag-o-meter. But as maddening as that sounds, I actually understood. There were funny bits but there weren't enough of them,

so give me some more of those

— which we did! The other mysterious note in this category had us baffled for a long time. “Too broad” was the note we got. Too broad? Did that mean the scene lapsed into the unbelievable? Was “too broad” short for “not real”? Because we had a lot of “not real” scenes and jokes in our story, and the studio seemed to like

those

! It took us awhile, but we finally figured it out. Too broad meant… “not funny!” It meant: “Doesn't work.”

And that's kind of a clue for every note a writer gets. If you want to get binary about it, at its most simple, any red flag offered by any reader or executive means “doesn't work.” How or why it doesn't work almost doesn't matter. It just means that the line or scene or character, as it is currently written, stopped the reading process, stopped the enjoyment of the story, and, that in and of itself, must be addressed. I've even talked to writers who are convinced a specific page note — for example, a problem on page 35 — might be about problems that happened several pages before. We may have started to lose the reader five or 10 pages back, so it isn't a bad idea to review the run-up to the actual note to see if the problem doesn't really lie earlier on.

Other little notes that I've heard over the years include:

►

Dial it up

or

Dial it down

– Often these phrases are heard in context of minor characters. Can we “dial up” the essence of that character and see or hear more? Can we get more scenes with him or her and make that role bigger? Or, conversely, can we “dial down” to make that character less so? In

Star Wars

, they “dialed up” Yoda as the “prequels” unfolded, but “dialed down” Jar Jar Binks. (If only it was done at the script stage!)

►

Too soft

– This was a note — particularly given to me as a family-film writer — that was often baffling. “Too soft” went hand in hand with the notion that my script had to be more “edgy.” Too

soft meant so sweet or homespun we need insulin shots to read it. But “too soft” can also mean the hero is passive, that there is not enough conflict, or the tone is out-of-date for the audience.

►

In your face

– Here's another peculiar one. I was once told that a scene someone felt was dull or not “big” enough, had to be more “in your face.” My best guess is this means we need the conflict to be greater, and whatever confrontation was on display — either as a whole or in a scene — had to have more to it. Again, it boils down to: If it “doesn't work,” our job is to make it work… or be prepared for executives to hire a writer who will!

One of my favorite aspects of the rewrite process — and working with others — is the frequent discussion that comes up about

“What would

really

happen?”

We bring different experiences to the development of any script, but it's amazing, no matter how wildly different we are, our sense of “natural law” is the same. And yet finding that consensus can lead to some memorable discussions.

Often these debates occur between notes sessions. We'll have a “tools-down” moment when everyone shares their personal philosophies about a fictional situation, and the different notion of what is logical as we see it. These conversations, examples of which follow, can be remarkable.

What is “justice”?

Let's say we're figuring out the punishment for a minor character in a story. Think of the one Jason Alexander plays in

Pretty Woman

. Toward the end of that film, jealous Jason attempts to rape Julia Roberts, and as his just desserts he is denied the friendship of — and a business deal with — Richard Gere. But should he have been more harshly dealt with? What about filing charges? What about reporting his behavior to his wife or his boss? Is Jason's punishment enough?

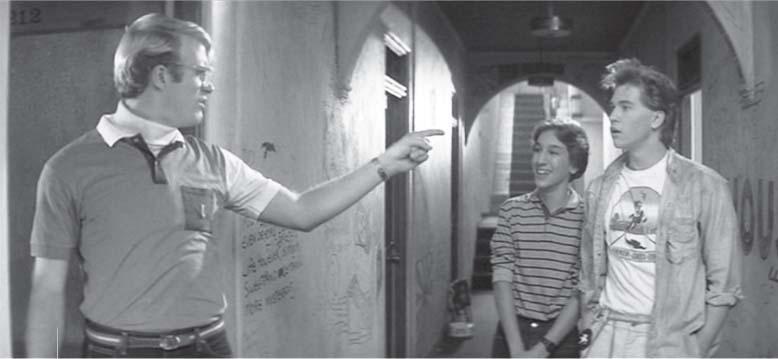

This same debate can be applied to another favorite example from the Val Kilmer-starring, Martha Coolidge-directed comedy,

Real Genius

. At the end of that film, Kent (Robert Prescott), the Cal Tech “snitch,” is implanted with a microchip in his fillings that makes him think God is talking to him, and directing him to help our heroes best the bad guys. His punishment is the “justice” of exclusion and embarrassment. But for a whole movie's worth of nasty things that Kent did to Val and his genius-IQ buddies — including sabotaging a vital experiment — is this enough? When Kent's nearly killed by a satellite laser beam in the Finale, and our heroes rush to save him, should they? Or does Kent deserve to die?

Real Genius

: Before he was Batman, Val Kilmer was a Real Genius up against the Big Snitch on Campus, Kent. But does Kent deserve to die?

What is “admirable”?

One of my favorite examples of “Save the Cat!” is when we first meet the title character in

Aladdin

, as the hungry waif steals some bread. He's let off the hook for his crime by giving his hard-earned prize to two orphans in an alley — thus

“saving the cat.” We are even shown Aladdin's sidekick, Abu the monkey, selfishly eating

his

stolen pita, and note the difference between them: Heroes not only have honor, but also the self-control their own pals lack! There's a very different “Save the Cat!” moment in

The Dark Knight

, when we meet Batman battling look-alikes and killer dogs. The “Save the Cat!” beat comes when Batman snaps the neck of one of the dogs — and the audience cheers! Are they right to? Does this show the same compassion that heroes in these kinds of movies are known for? And if not, why are we still rooting to see Batman defeat the Joker? Is it only because the Joker is “worse”? Well, what's worse than strangling a dog?

What is “proper”?

Once during a notes meeting for a movie script a partner and I had written, we had a discussion about the hero who had just been stood up by his girlfriend. What should be our guy's response? The reactions around the table were kinda tame, varying from “Call the girl and find out what happened” to “Go to her apartment to see if she's okay.” Finally during a pause in the proceedings, a male producer shouted: “Dump the bitch!” to which everyone responded in horror.

On the surface, our reaction to the note was a reaction to him.

Chauvinist! Sexist! Gold-chain-wearing Hollywood producer!

we all were secretly thinking. But in fact what he was pointing out… made sense. What he was

really

saying was that in his opinion he lost respect for a character that didn't stand up for himself. Having been dissed, having been put down by being stood up, maybe being understanding wasn't “proper” at all? It also spoke to a problem we'd been having all along: Our hero was soft (there's that word again), and while that's okay in a rom-com — when the hero is a goofy loser about to learn that his gal is cheating on him — that wasn't the case in this story. In fact, what might be “proper” in a real life situation wasn't appropriate here either!