Save the Cat! Strikes Back: More Trouble For... (15 page)

Read Save the Cat! Strikes Back: More Trouble For... Online

Authors: Blake Snyder

Tags: #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #Screenwriting

It's time for the “rewrite.”

And as important as it is that I and my patrons are all on the same page — literally — this is where the real work starts.

The one thing I became a writer hoping to avoid.

But if we want to continue to be highly paid professionals, or just test our ability to be good and sober citizens, we have to employ all new ways to grin and bear it. So how do we do that — and still maintain the integrity of our story?

Tops on the mind of every writer is the fine line we walk every time we saunter into the studio: Is it our job to speak, on behalf of a script we know better than anyone, by defending every comma? Or are we to just be good sports, go along to get along, and help Og and company realize their vision too — going so far as to incorporate a “vision”we're sure Og came up with by driving past the same billboard we did on our way to the meeting?

If we are to learn one thing from the

Cat!

method, it's that “no man is an island.” More than any other creative venture, filmmaking is a group grope, a team sport, and now you must pass the ball, or be passed, or worse, be taken out of the game.

Well, here's a flash: You aren't the only one who's scared.

And I'm here to tell you how wonderful “they” can be and how safe you are in their presence. How do I know? How can I be so assured that your next rewrite will be the best one ever?

Because I will give you 100 years’ worth of experience to deal with any crisis in “the room” — and give you a peek into the future of the development process — to let us all…

strike back!

I have just returned from a meeting with my writer's group. This small group technique is one I encourage all writers to pursue as they continue to develop their stories. In fact, we have

Cat!

writers groups set up all over the world.

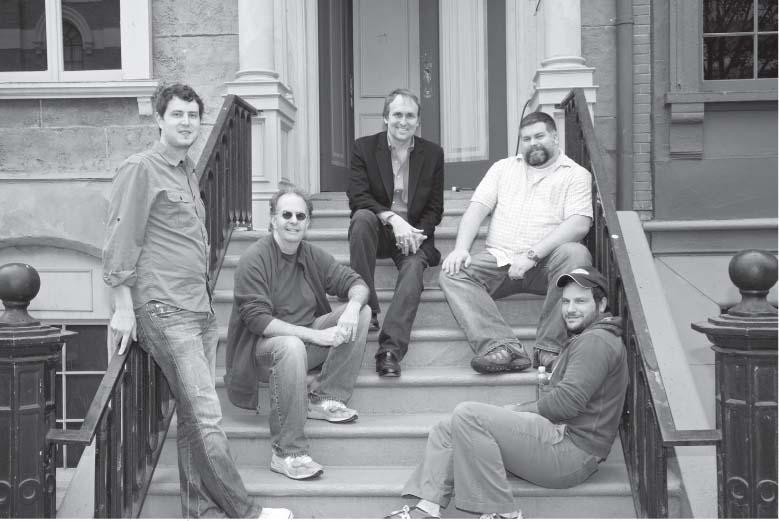

Writers Group: Ben Frahm, Dan Goldberg, Blake Snyder, Dean DeBlois, and Jeremy Garelick on the New York set on the Warner Bros. backlot.

Not to brag or anything, but take a look at who's in mine:

Dan Goldberg

, screenwriter of

Meatballs

,

Stripes

, and

Feds

, and now a producer of such hits as

Old School

and

The Hangover

.

Jeremy Garelick

, screenwriter of

The Break-Up

,

The Hangover

(uncredited), and the upcoming

Baywatch

.

Dean DeBlois

, screenwriter/director of

Lilo & Stitch

and

How to

Train a Dragon

.

And freshman

Ben Frahm

, whose first script,

Dr. Sensitive

, sold to Tom Shadyac and Universal for $350,000 against $500,000.

How did I get so lucky?

Our group got its start thanks to Dan, who in 2007 was giving a talk to screenwriters here in Los Angeles and mentioned

Save the Cat!

as a new favorite. Through the grapevine, I heard this and called up Dan to introduce myself and say thanks! Dan wondered about my

Cat!

workshops and we decided to form a group based on the

Cat!

beats.

Dean had taken my class; so had Ben. In fact it was in one of my early workshops where Ben, new arrival to L.A. via Cornell, worked out the initial beats for

Dr. Sensitive

, and Dean had developed a “Monster in the House” script he sold to Disney. Jeremy and I had met thanks to my manager, Andy Cohen, and was also a

Cat!

fan. We'd often spoken about getting together to pitch ideas and read scripts in progress using

Cat!

as a guide.

Our initial meetings were supercharged.

Seriously, these are some of the fastest story guys I know, with amazingly fluid minds. Because we are a mutual admiration society, and have such respect for each other's work, we are only interested in making great ideas greater, and straightening our story spines. And the fact

your

script isn't

my

script helps.

What is most surprising about this group, though, is that our problems are the same. Despite our professional accomplishments, we are just as likely to go down the road of a bad idea, or not thoroughly figure out what it takes to make a good idea better. Maybe because of our success, too, we are sometimes less inclined as individuals to admit our blind spots to higher-ups, but in a group of peers like this, we are more likely to let our guard down — and our egos — and see a “note” as a plus.

In a recent session, in point of fact, the subject of “getting notes” was the topic. Dean had two projects at two separate studios and was sharing the joy and the pain of…

… the rewrite process.

As we helped Dean prepare for his meetings, we were playing our favorite game, “Guess what they'll say?” This is the world-weary

writer's mental jujitsu that tries to anticipate how bad it will get in that room, what really obvious thing in our script or story

won't

be obvious and

must

be made clearer?

But at core was the fear the process makes scripts worse.

As we played this terrible game, we were brought up short by the more experienced members in our group, particularly Dan.

No one is trying to wreck your script!

was his steadying advice. Having been on both sides of the table, both as a writer getting notes on

Meatballs

and

Stripes

from the legendary Ivan Reitman, and now as a producer himself giving notes to writers, Dan has more experience than any of us. So much of learning is told in stories, and Dan has told us about his experiences writing the classic Bill Murray comedies — and how many blind alleys had to be gone down, and trees slain, in order to get what wound up on screen that seemed, in the end, so simple — and simply great.

No, no one is

purposely

trying to wreck your script!

But since getting and giving notes is about communicating ideas — and since we all see different movies as influences — this is where the pushmi-pullyu that is the script development process sometimes earns that reputation.

When we had finished our work one afternoon, I asked My Guys for a little feedback on how they approach the challenge. How do they negotiate the rewrite process, both as writer, and in Dan's case as producer, to see the world from the executive's point of view?

How have we gotten through the challenge of hearing notes, responding to them, and delivering a script that is still ours?

And what are the benefits of possibly altering the current methods of script development in the future by replacing the “top-down” model (in which executives dictate notes to writers) with a “peer-to-peer” model (like the one we use in our writers groups)?

In either case, success starts with the right attitude.

You are about to attend your first notes session for a script you've just sold. You're still getting the confetti and champagne out of your hair, and now it's time to face the Muzak. You've heard hints ever since the sale that “of course, there're some improvements” to be made to the script, which now may or may not have devolved into rumors of “a page one rewrite.” Since “the day begins the night before,” it's a good idea to re-read your script and get up to speed. But in terms of making notes on what you want to fix… don't. Wait. Depending on your deal, you'll likely have at least one more crack at this (

a draft and a set

is the term most often used to describe a rewrite and a polish).

So relax.

The players in the meeting can be any combination of producer, producer's development executive, studio executive assigned to this project, and a clutch of assistants who will one day be executives — so be very nice to them! Usually your ally is the producer who is the “champion” of the project, but he only gets paid once the movie is in production. Besides you, the producer has most to gain. He has twelve more of these projects around town, and is usually, but not always, the best dressed.

After an initial discussion about hybrid cars, you begin.

Yes, everyone loves your script. Yes, they might even love you. But you're here to “write it into production.” In truth, as exciting as it is to make a spec sale, the real A-list writers are the ones studios turn to who can fix problems. And often, if you are the original writer, this is the test: Can you stay on? Can you hear notes and deliver what's requested? Or are you going to reveal yourself to be nothing more than the guy who came up with the concept, and thank you very much, there's the door.

If this is your first time selling a script, take some advice from Ben Frahm. Ben is that guy who grabbed the brass ring. He came up with, wrote, and sold a big spec script. Due to the sale and his skill at creating other winning movie ideas (Ben has a true gift for

concept), he got an agent at CAA, and is repped by Underground Management, who nurtured the project. But the #1 thing was doing a great job on the rewrite:

In looking back at my studio notes from Universal for

Dr. Sensitive

, I would offer fellow writers that it's always important to stay positive about the project. No matter what happens, keep your head up, and keep working hard. It is so important for writers, especially young writers, to prove to everyone — in particular those at the studio level — that you are a hard-working professional, and totally committed to the project!

There are other situations where that attitude really helps. Perhaps you have been asked to revive a stalled project. Your “take” has been vetted, and now you're here to make sure all agree before sending you off to write. There is also the situation when you have been brought on to write for an

element

— an actor or a director — who wants changes. This is the situation I was in rewriting

Big

,

Ugly Baby!

for Henry Selick (

Coraline

,

Nightmare Before Christmas

), though just talking to Henry was privilege enough. Whatever the problem, you're here to fix it. And as you'll hear many times: “You're the writer!” — a refrain that begins to grate almost immediately.

Surprise, surprise: Your work is not done. But what is the headline? What are the main one, two, or three most urgent concerns to address in this new draft? Often, a group consensus has formed before you walked in the door. We've all agreed: That character, section, whole act, or subplot has got to go or be improved. Now it's just a matter of explaining it to you. And Dan has advice for executives — informed by his years as a writer:

Don't give written notes… at least not before having a meeting to discuss the notes. As a writer, I have never, ever, not had an extreme visceral angry reaction to reading notes from a studio, no matter how eventually good and succinct they

turned out to be. I think it has something to do with the impersonal and cold nature of it — as if these notes are written in stone. There is very little nuance to notes that can naturally occur in a face-to-face meeting.I tell my producing team: Do your homework. Go over the script and make notes of your feelings on your first read, places that the script lags, or places that really work. Don't worry about having solutions to the problem areas. That is open for discussion. You will be surprised how something can be solved in a way that was unexpected. In the face-to-face meeting with the writer(s), first go over general sweeping feelings on the script as a whole. Be frank, but emphasize that everything is up for grabs. It is a discussion, not a list of demands.

After the general discussion, where everyone is encouraged to talk in generalities, go through the script page by page, with everyone giving their thoughts on specific areas. It is also best when there is someone who can stop annoyingly nit-picky notes from getting out of hand, so you can move on to the next topic.

Unfortunately, the result of getting poor, conflicting, or confusing notes, as Dean points out, can lead to problems:

The notes that are less specific are what cause trouble. They have to do with “broadening the audience,” making it “four-quadrant,” “castable,” “edgy,” and “less earnest.” The last round of notes I received were amusing. Eight pages of contradicting notes that called for the script to be all things to all people. “We love the mystery element. Let's fill it with complex twists and nail-biting turns.” “Let's make the mystery take a back seat to the blossoming relationship.” That kind of thing, page after page. For me, the toughest part of a rewrite is extracting the actual note from the suggestion(s) and finding a way to address it within the complex workings of the story. It demands a lot of planning because of the trickle-down effect of every alteration.