Savage Night (17 page)

Authors: Jim Thompson

I

stayed in the basement as much as I could. She couldn’t get me down there. She wasn’t good enough on that little foot and knee to come down the stairs. And somehow I had to hang on.

The last race was over, and I’d lost them all, but still I hung on. I seemed to be right on the point of finding something…of finding out something. And until I did I couldn’t leave.

I found out one evening when I was coming up out of the basement. I came even with the floor and turned sideways on the steps, putting down the stuff I’d brought up. And I’d brought a pretty big load because I didn’t want to come up any more often than I had to; and I was kind of dizzy. I leaned my arms on the floor, steadying myself. And then my eyes cleared, and there was the little foot and leg right in front of me. Braced.

The axe flashed. My hand, my right hand, jumped and kind of leaped away from me, sliced off clean. And she swung again and all my left hand was gone but the thumb. She moved in closer, raising the axe for another swing…

And so, at last, I knew.

B

ack there. Back to the place I’d come from. And, hell, I’d never been wanted there to begin with.

“…but where else, my friend? Where a more logical retreat in this tightening circle of frustration?”

She was swinging wild. My right shoulder was hanging by a thread, and the spouting forearm dangled from it. And my scalp, my scalp and the left side of my face was dangling, and…and I didn’t have a nose…or a chin…or…

I went over backwards, then down and down and down, turning so slowly in the air it seemed that I was hardly moving. I didn’t know it when I hit the bottom. I was simply there, looking up as I’d been looking on the way down.

Then there was a slam and a click, and she was gone.

T

he darkness and myself. Everything else was gone. And the little that was left of me was going, faster and faster.

I began to crawl. I crawled and rolled and inched my way along; and I missed it the first time—the place I was looking for.

I circled the room twice before I found it, and there was hardly any of me then but it was enough. I crawled up over the pile of bottles, and went crashing down the other side.

And he was there, of course.

Death was there.

A

nd he smelled good.

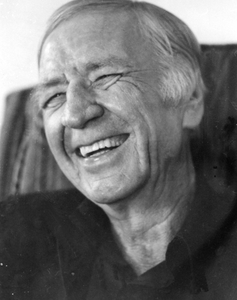

James Meyers Thompson was born in Anadarko, Oklahoma, in 1906. In all, Jim Thompson wrote twenty-nine novels and two screenplays (for the Stanley Kubrick films

The Killing

and

Paths of Glory

). Films based on his novels include

The Getaway, The Killer Inside Me, The Grifters,

and

After Dark, My Sweet.

Now and On Earth

In May 2012, Mulholland Books will publish Jim Thompson’s

Now and On Earth

. Following is an excerpt from the novel’s opening pages.

I

got off at three-thirty, but it took me almost an hour to walk home. The factory is a mile off Pacific Boulevard, and we live a mile up the hill from Pacific. Or up the mountain, I should say. How they ever managed to pour concrete on those hill streets is beyond me. You can tie your shoelaces going up them without stooping.

Jo was across the street, playing with the minister’s little girl. Watching for me, too, I guess. She came streaking across to my side, corn-yellow curls bobbing around her rose-and-white face. She hugged me around the knees and kissed my hand—something I don’t like her to do, but can’t stop.

She asked me how I liked my new job, and how much pay I was getting, and when payday was—all in one breath. I told her not to talk so loud out in public, that I wasn’t getting as much as I had with the foundation, and that payday was Friday, I thought.

“Can I get a new hat then?”

“I guess so. If it’s all right with Mother.”

Jo frowned. “Mother won’t let me have it. I know she won’t. She took Mack and Shannon downtown to buy ’em some new shoes, but she won’t get me no hat.”

“ ‘No hat’?”

“Any hat, I mean.”

“Where’d she get the money to go shopping with? Didn’t she pay the rent?”

“I guess not,” Jo said.

“Oh, goddam!” I said. “Now, what the hell will we do? Well, what are you gaping for? Go on and play. Get away from me. Get out of my sight. Go on, go on!”

I reached out to shake her, but I caught myself and hugged her instead. I cannot stand anyone who is unkind to children—children, dogs, or old people. I don’t know what is getting the matter with me that I would shake Jo. I don’t know.

“Don’t pay any attention to me, baby,” I said. “You know I didn’t mean anything.”

Jo’s smile came back. “You’re just tired, that’s all,” she said. “You go in and lie down and you’ll feel better.”

I said I would, and she kissed my hand again and scurried back across the street.

Jo is nine—my oldest child.