Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II (67 page)

Read Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II Online

Authors: Keith Lowe

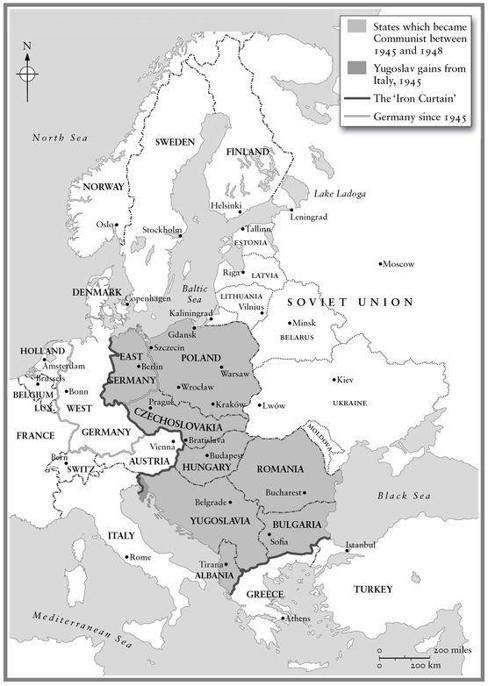

12. The division of Europe in the Cold War

I do not want to carry this comparison too far, because the capitalist model of politics was self-evidently more inclusive, more democratic and ultimately more successful than Stalinist communism. But it is also true to say that the conduct of those ‘democratic’ countries in the aftermath of the war was often far from perfect. In some instances it was demonstrably worse than the Communists’ – the treatment of peasants in the south of Italy, for example, who were denied the land reforms they had been promised by government, compares badly with the progressive attitude in eastern Europe during the early days of Communist rule. Neither side had a monopoly on virtue. In a continent as large and diverse as Europe, it is always unwise to generalize.

And yet, at the time, such generalization was increasingly apparent. Ideologues from the left characterized everyone who did not share their world view as ‘fascist imperialists’, ‘reactionaries’ and ‘bloodsuckers’. Ideologues from the right portrayed anyone with even moderately left-wing views as ‘Bolsheviks’ or ‘terrorists’. As a consequence, those in the middle were increasingly forced to take one side or the other – generally whichever side appeared strongest at the time. In the words of one of the fathers of international communism, ‘one either leans to the side of imperialism or to the side of socialism. Neutrality is mere camouflage and a third road does not exist.’

3

The consequences of picking the wrong side, particularly in eastern Europe or Greece, could be fatal.

As I have shown, this conflict of ideologies was not new to the postwar period. Leftist partisans and rightist militias had regularly fought each other while the main war was still in progress, and sometimes even agreed local ceasefires with the Germans in order to concentrate more fully on fighting each other. Local civil wars ran alongside the main war not only in Greece but in Yugoslavia, Italy, France, Slovakia and Ukraine. For fanatics on both sides, what really mattered was not so much the national war against German occupation, but the more deep-rooted struggle between those with nationalist ideals and those with Communist ones.

In this ideological struggle between right and left, the defeat of Germany in 1945 was significant only because it removed the most powerful sponsor of the right in Europe. It did not mean that the ideological war was over. Far from it: for many Communists the Second World War was not a discrete event, but merely a staging post in a much larger process that had already lasted decades. The defeat of Hitler was not an end in itself, but a springboard from which the next stage of the struggle would be launched. The Communist seizure of control throughout eastern Europe came to be viewed as part of the same process, which would end, according to Marxist doctrine, with the ‘inevitable’ victory of communism throughout the world.

It was only the presence of the Western Allies, and especially the Americans, that prevented communism from spreading still further across Europe. It is no wonder, therefore, that Communists in the postwar years portrayed the Americans as imperialist conspirators, just as they demonized the bourgeois opposition in Hungary or Romania as ‘Hitlero-fascists’. In the Communist mind there was no fundamental difference between dictators such as Hitler and more democratic figures such as President Truman, Imre Nagy or Iuliu Maniu – all were representatives of an international system that exploited workers, and tried continually to stamp out socialism.

As for the Americans, they soon found themselves being dragged towards the opposite pole. The war against communism was not something that they had planned on entering, but by becoming involved in the Second World War they also necessarily became embroiled in the larger political process of right against left. In their policing of Europe during the aftermath of the war they inevitably found themselves bogged down in the numerous local conflicts that broke out between the two factions – and in each case they instinctively took the side of the right, even in those instances where it meant standing behind a brutal dictatorship, such as in Greece. With time, and experience, they too began to demonize their opponents, and by the 1950s the measured approach of Americans like Dean Acheson or George C. Marshall had given way to the violent rhetoric epitomized by Senator Joe McCarthy. McCarthy’s portrayal of American Communists as ‘a conspiracy on a scale so immense as to dwarf any previous such venture in the history of man’ was every bit as irrational as eastern Europe’s anti-Americanism.

4

It was the polarization of Europe, and ultimately the whole world, into these two camps that was to become the defining characteristic of the second half of the twentieth century. The Cold War was unlike any conflict that had ever been waged before. In its scale it was just as vast as either of the two world wars, and yet it was not fought predominantly with guns and tanks, but through the hearts and minds of civilians. To win these hearts and minds, both sides proved willing to employ whatever means were necessary, from the manipulation of the media to the threat of violence or even the incarceration of young Greek girls in political prison camps.

For Europe, and for Europeans, this new war would simultaneously show the importance and the impotence of the continent on the world stage. As in both of the global wars of the previous thirty years, Europe was still the main theatre of conflict. But for the first time in their history, Europeans would not be the ones pulling the strings: from now on they would be mere pawns in the hands of superpowers outside the borders of their own continent.

In his memoirs of the late 1940s and 50s, published after his death following the famous ‘umbrella assassination’ in London in 1978, the Bulgarian dissident writer Georgi Markov told a story that is emblematic of the postwar period – not only in his own country, but in Europe as a whole. It involved a conversation between one of his friends, who had been arrested for challenging a Communist official who had jumped the bread queue, and an officer of the Bulgarian Communist militia:

‘And now tell me who your enemies are?’ the militia chief demanded.

K. thought for a while and replied: ‘I don’t really know, I don’t think I have any enemies.’

‘No enemies!’ The chief raised his voice. ‘Do you mean to say that you hate nobody and nobody hates you?’

‘As far as I know, nobody.’

‘You are lying,’ shouted the Lieutenant-Colonel suddenly, rising from his chair. ‘What kind of a man are you not to have any enemies? You clearly do not belong to

our

youth, you cannot be one of

our

citizens, if you have no enemies! … And if you really do not know how to hate, we shall teach you! We shall teach you very quickly!’

1

In a sense, the militia chief in this story is right – it was virtually impossible to emerge from the Second World War without enemies. There can hardly be a better demonstration than this of the moral and human legacy of the war. After the desolation of entire regions; after the butchery of over 35 million people; after countless massacres in the name of nationality, race, religion, class or personal prejudice, virtually every person on the continent had suffered some kind of loss or injustice. Even countries which had seen little direct fighting, such as Bulgaria, had been subject to political turmoil, violent squabbles with their neighbours, coercion from the Nazis and eventually invasion by one of the world’s new superpowers. Amidst all these events, to hate one’s rivals had become entirely natural. Indeed, the leaders and propagandists of all sides had spent six long years promoting hatred as an essential weapon in the quest for victory. By the time this Bulgarian militia chief was terrorizing young students at Sofia University, hatred was no longer a mere by-product of the war – in the Communist mindset it had been elevated to a duty.

There were many, many reasons not to love one’s neighbour in the aftermath of the war. He might be a German, in which case he would be reviled by almost everyone, or he might have collaborated with Germans, which was just as bad: most of the vengeance in the aftermath of the war was directed at these two groups. He might worship the wrong god – a Catholic god or an Orthodox one, a Muslim god, or a Jewish god, or no god at all. He might belong to the wrong race or nationality: Croats had massacred Serbs during the war, Ukrainians had killed Poles, Hungarians had suppressed Slovaks, and almost everyone had persecuted Jews. He might have the wrong political beliefs: both Fascists and Communists had been responsible for countless atrocities across the continent, and both Fascists and Communists had themselves been subjected to brutal repression – as indeed had those subscribing to virtually every shade of political ideology between these two extremes.

The sheer variety of grievances that existed in 1945 demonstrates not only how universal the war had been, but also how inadequate is our traditional way of understanding it. It is not enough to portray the war as a simple conflict between the Axis and the Allies over territory. Some of the worst atrocities in the war had nothing to do with territory, but with race or nationality. The Nazis did not attack the Soviet Union merely for the sake of

Lebensraum:

it was also an expression of their urge to assert the superiority of the German race over Jews, Gypsies and Slavs. The Soviets did not invade Poland and the Baltic States only for the sake of territory either: they wanted to propagate communism as far westwards as they were able. Some of the most vicious fighting was not between the Axis and the Allies at all, but between local people who took the opportunity of the wider war to give vent to much older frustrations. The Croat Ustashas fought for the sake of ethnic purity. The Slovaks, Ukrainians and Lithuanians fought for national liberation. Many Greeks and Yugoslavs fought for the abolition of the monarchy - or for its restoration. Many Italians fought to free themselves from the shackles of a medieval feudalism. The Second World War was therefore not only a traditional conflict for territory: it was simultaneously a war of race, and a war of ideology, and was interlaced with half a dozen civil wars fought for purely local reasons.

Given that the Germans were only one ingredient in this vast soup of different conflicts, it stands to reason that their defeat did not bring an end to the violence. In fact, the traditional view that the war came to an end when Germany finally surrendered in May 1945 is entirely misleading: in reality, their capitulation only brought an end to one aspect of the fighting. The related conflicts over race, nationality and politics continued for weeks, months and sometimes years afterwards. Gangs of Italians were still lynching Fascists late into the 1940s. Greek Communists and Nationalists, who first fought one another as opponents or collaborators with Germany, were still at each other’s throats in 1949. The Ukrainian and Lithuanian partisan movements, born at the height of the war, were still fighting well into the mid-1950s. The Second World War was like a vast supertanker ploughing through the waters of Europe: it had such huge momentum that, while the engines might have been reversed in May 1945, its turbulent course was not finally brought to a halt until several years later.

The hatred demanded by the Bulgarian militia chief in Georgi Markov’s story was of a very specific kind. It was the same hatred that Soviet propagandists like Ilya Ehrenburg and Mikhail Sholokhov demanded during the war, and that political commissars tried to promote amongst the army units in eastern Europe throughout the period. If the student he was terrorizing had had any knowledge of Stalinist theory – something that would become a central part of every Bulgarian student’s education in the years to come – he would have known precisely who his enemies were.

The angry, resentful atmosphere that pervaded throughout Europe in the aftermath of the war was the perfect environment for stirring up revolution. Violent and chaotic as it was, the Communists did not see this atmosphere as a curse but as an opportunity. Before 1939 there had always been tensions between capitalists and workers, lords and peasants, rulers and subjects – but they had usually been local, short-lived affairs. The war, with its years of bloodshed and privation, had inflamed these tensions beyond anything that the prewar Communists could have imagined. Large sections of the population now blamed their old governments for dragging them over the abyss into war. They despised businessmen and politicians for collaborating with their enemies. And, when much of Europe was on the brink of starvation, they hated anyone who appeared to have come out of the war better off than them. If workers had been exploited before the war, then during the war that exploitation had reached its utmost extremes: millions had been enslaved against their will, and millions more had been quite literally worked to death. It is unsurprising that so many people throughout the continent turned to communism after the war: the movement not only appealed as a refreshing and radical alternative to the discredited politicians who had gone before, but gave people an opportunity to vent all the anger and resentment that had built up during those terrible years.