Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II (53 page)

Read Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II Online

Authors: Keith Lowe

Arguably, therefore, Russian influence in the country was already just as important as British influence, and certainly more than the 10 per cent granted by Churchill’s scrap of paper. Had Stalin instructed the Greek Communists to seize control of the country, it is quite possible that they could have done so. The Red Army was already within touching distance of the north of the country on the borders of Bulgaria, and the Communist Partisans of Yugoslavia were also linking up with their comrades in northern Greece. The British presence in October 1944 was tiny compared to that of EAM/ELAS; and when they arrived in Athens they found that the

andartes

had already liberated the city. Despite this, there was no attempt by the Communist Party to seize power at a national level. This was partly because the resistance were fairly disorganized, and partly also because there were many non-Communists within the EAM structure who threatened to withdraw their support if the organization were to seize power for itself. But it was mostly because Stalin had kept his word: in the run-up to the Moscow conference he had sent a mission to Greece to instruct Communists there to cooperate with the British.

4

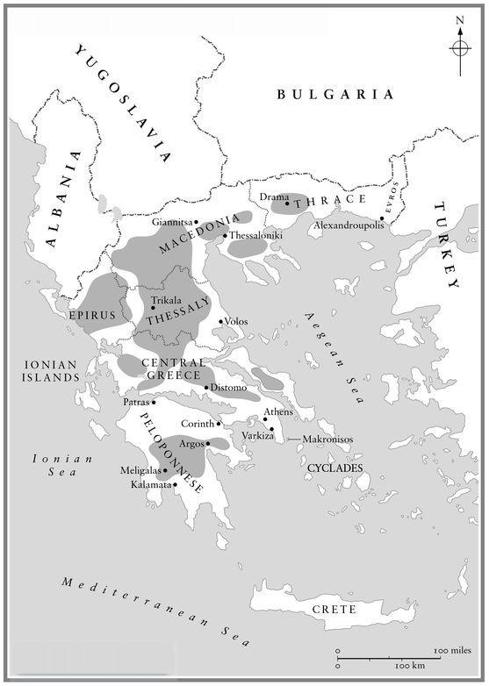

10. Areas of Greece under partisan control, 1944

As in France and Italy, there were many amongst the rank and file of the Communist Party – and even some within the leadership – who could not understand why they should stand back and allow others to take control. In a bitter speech to the Communist Party’s Central Committee in the summer of 1944, EAM general secretary Thanasis Hadzis complained that the resistance was being betrayed. EAM/ELAS had spent several years fighting the occupier and establishing their power across most of Greece: why should they now bow to the British? ‘We cannot follow two paths,’ he insisted. ‘We must make our choice.’

5

Many Greek resistance leaders suspected the British of wanting to reduce Greece to a virtual colony ruled by a puppet government, just as the Germans had done before them.

In the weeks after the liberation, tensions between the British and EAM/ELAS increased. The British military hierarchy mistrusted the motives of the

andartes

and, as in France, regarded them as a volatile group of amateurs with a tendency to fire off their weapons seemingly for the sake of it. Churchill himself claimed that he was fully expecting a clash with EAM, and sent instructions to the officer in command of Allied forces in Greece, General Ronald Scobie, to expect a coup d‘état at any moment. If it materialized, Scobie’s instructions were to use all force necessary ‘to crush ELAS’.

6

Conversely, members of EAM/ELAS were extremely mistrustful of British motives. They could not help noticing that the British continued to support the return of the Greek king, and that they appeared to be protecting some former collaborators rather than bringing them to trial. They also seemed to be supporting the appointment of some fiercely anti-Communist officials to key security posts. When, for example, following liberation George Papandreou’s so-called ‘government of national unity’ appointed Colonel Panagiotis Spiliotopoulos as military commander of the Athens area in October 1944, the British refused to intervene. Spiliotopoulos had actively coordinated right-wing anti-Communist groups during the occupation, and was regarded by ELAS as a collaborator. Neither did they intervene when a group of senior Greek army officers in Italy began to speak openly of overthrowing the Papandreou government and replacing it with an extreme right-wing administration.

7

Such attitudes, combined with the unfortunate tendency of some British officials, in the words of the American ambassador, to treat ‘this fanatically freedom-loving country … as if it were composed of natives under the British Raj’, meant that it was only a matter of time before some kind of dramatic split occurred.

8

That split came at the beginning of December, less than two months after the liberation of Athens, when the ministers who represented EAM in Papandreou’s cabinet resigned en masse. Their gripe was the same as that of the resistance parties in France and Italy: they were unwilling to disarm themselves and hand over control to a newly formed National Guard, at least until right-wing former collaborators had been comprehensively weeded out from the ranks of the police. Unlike France, however, there was no single, charismatic leader who was strong enough, and politically astute enough, to take on both the Communists and the purge of the police. And unlike Italy, the Communists themselves were not quite united enough to agree, however reluctantly, to a compromise agenda. Neither did the Allies have a strong enough presence in the country to compel the two sides to come to an agreement: British forces in Greece were only a fraction of the size of the massive Allied armies that were currently stationed in France and Italy. The political stalemate produced a tension that was tangible at all levels of society. As the writer George Theotokas wrote in his diary, ‘It only needs a match for Athens to catch fire like a tank of petrol.’

9

On 3 December, the day after the EAM ministers walked out of the government, demonstrators took to the streets of Athens. They congregated in Syntagma Square where, for reasons that remain a mystery even today, the police opened fire, killing at least ten and injuring over fifty. British troops who were present maintain that this was simply because the Athens police lost their nerve, but some Greek leftists claimed that it was a deliberate act of provocation.

10

Whatever the motives for opening fire, it unleashed the same cycle of violence that had been in abeyance for only a matter of weeks.

Remembering the brutality of the Greek security forces during the occupation, EAM supporters immediately blockaded and attacked police stations across the city. For the sake of law and order, British forces were now obliged to step in. At first they were pinned down in central Athens by ELAS snipers, but gradually they broke out into the south of the city and into the ‘Red’ suburbs, where they fought running street battles with former Greek resistance fighters. It was the only time during the war or its aftermath when Allied troops in western Europe found themselves fighting the very resistance groups they were supposed to have liberated. With true colonial hauteur, Churchill informed General Scobie that he was free ‘to act as if you were in a conquered city where a local rebellion is in progress’.

11

Accordingly, British batteries of 25-pounders opened fire on the ‘Communist’ suburb of Kaisariani, and RAF fighter planes even strafed ELAS positions in the pine woods and apartment blocks overlooking the centre of Athens. For the terrified non-combatants who found themselves caught in the crossfire, this was the last straw: women and children were being wounded and killed in attacks by the British that appeared completely indiscriminate. When British medics visited a first-aid post in the suburb of Kypseli they had to pretend to be American in order to avoid being lynched by angry Athenians. Some of those who had been wounded when the Royal Air Force strafed a local square told them that ‘they had liked the English, but now they knew that the Germans were gentlemen’.

12

Over the course of December 1944 and January 1945 the fighting at last began to develop into a class war, with all its worst characteristics. On the one side were the fiercely fanatical EAM/ELAS fighters, who by now were convinced that the British were trying to reinstate both the monarchy and a right-wing dictatorship; on the other side was an uneasy coalition of British troops, Greek monarchists and anti-Communists, many of whom were equally convinced that EAM was trying to stage a Stalinist revolution. Events escalated when the British rounded up some 15,000 suspected left-wing sympathizers and deported over half of them to camps in the Middle East. The andartes responded by seizing thousands of bourgeois hostages in Athens and Thessaloniki and marching them through the snow up into the mountains. Hundreds of these supposed ‘reactionaries’ – often only identified as such because of their relative wealth – were executed and buried in mass graves.

13

By the end of January both sides were exhausted by the fighting. That February they signed a peace agreement at the seaside town of Varkiza, in which ELAS agreed to disband and lay down their weapons, and the provisional government agreed to press forward with the purge of collaborators. An amnesty was declared for all political offences committed between 3 December 1944 and 14 February 1945, except for ‘common-law crimes against life and property which were not absolutely necessary to the achievement of the political crime concerned’.

14

Had both sides stuck to the agreement then perhaps the matter might have rested there. But, as would soon become apparent, the government had no real power over the right-wing bands that were now forming all over the country, nor even its own security forces. A backlash against EAM/ELAS was about to begin that would eventually lead to civil war.

The Character of Communist Resistance

It is easy to feel sympathy with the resistance fighters in France, Italy and Greece who, despite fighting courageously and successfully for the liberation of their countries, were often not only denied any reward by their postwar governments, but actively suppressed. Members of the Communist resistance were prevented from taking any positions of real power in the postwar governments of all three countries. Former heroes were arrested for deeds that many regarded as legitimate acts of war, and prosecuted with a ferocity that was conspicuously lacking in the official handling of collaborators. And to add insult to injury, stories of their heroic wartime exploits were brushed aside in favour of more dubious myths about Communist ‘crimes’ during the various purges across Europe. Influential people on the right made sure that the threat of Communist disorder, and even revolution, was exaggerated at every possible opportunity.

However, it is important not to dismiss

all

the claims made by the right. The left-wing resistance groups were not made up entirely of innocent idealists, struggling against the forces of tyranny for a better world – there were also many brutal realists who were more than willing to use tyranny themselves in order to push through their ideological reforms. It is impossible to paint the struggle between right and left in black-and-white terms: the methods, motives and allegiances of both sides are too tangled to unravel with anything approaching simplicity. Nowhere is this better exemplified than in Greece during and after the war. Here, more than in any other country, terror was freely employed by all sides upon a frightened population who found it increasingly difficult to avoid being sucked up into the war of ideologies.

The wartime rise of EAM was something completely new in Greece. The country had no tradition of mass ideological movements before the occupation, and politics tended to be something that was imposed upon the country from the top down, with little relevance to the working classes, particularly in the countryside. During the war, however, the brutal occupation of the Germans, Italians and Bulgarians, coupled with hunger and privation, had a deeply radicalizing effect upon the Greek population. Farmers, workmen and even women, who had previously had little use for politics, now saw it as the only way to bring sanity to a world gone mad with destruction. They turned to EAM in their hundreds of thousands, because EAM offered not only the possibility of resistance to occupation but the promise of a better world once the war was over.

The achievements of EAM at a local level are phenomenal, particularly since they occurred during a brutal war when their very existence was considered illegal by the occupying authorities.

15

In a time of famine they organized land reform, and the even distribution of food stocks. They instituted a new and highly popular form of ‘people’s justice’ that was conducted in villages rather than in local towns, heard by local juries rather than expensive lawyers and judges, and conducted in demotic rather than in formal High Greek, which was like a foreign language to most Greek peasants. They created almost a thousand village cultural groups across Greece, sponsored dozens of travelling theatre groups and published newspapers that were read throughout the country. They created countless schools and nurseries that provided education for those who had never before had the opportunity. They encouraged youth groups, and the emancipation of women – indeed, it was EAM who first gave Greek women the vote in 1944. They mended roads and created unprecedented communications networks. These achievements were particularly notable in the remoter parts of the Greek mountains that had been all but ignored by prewar politicians. According to Chris Woodhouse, a British secret agent in Greece during the war, ‘EAM/ELAS set the pace in the creation of something that Governments of Greece had neglected: an organized state in the Greek mountains’. It was only thanks to EAM that the ‘benefits of civilization and culture trickled into the mountains for the first time’.

16

Their popularity in many parts of Greece was founded upon their ability to change people’s lives for the better, and their willingness to engage not only with village notables but with ordinary people.