Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II (38 page)

Read Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II Online

Authors: Keith Lowe

Some witnesses remember Jews being thrown from the windows into the street below. The head of the Jewish Committee was shot in the back while he was phoning for help. Later, when 600 workers from the Ludwików foundry arrived shortly after midday, some fifteen or twenty Jews were beaten to death with iron bars. Others were stoned, or shot by policemen or soldiers. The list of dead included three Jewish soldiers who had won the highest combat decorations fighting for Poland, and also two ordinary Poles who had apparently been mistaken for Jews. Also killed that day were a pregnant mother and a woman who had been shot along with her newborn baby. In total, forty-two Jews were killed at Kielce, and as many as eighty others injured. A further thirty or so were killed in related assaults on the local railways.

48

The striking thing about this massacre was the fact that the entire community had taken part, not only men but also women; not only civilians but also policemen, militiamen and soldiers – the very people who were supposed to be keeping law and order. The racist myth of blood libel had been invoked, but the Catholic Church did nothing to refute this myth, or to denounce pogroms. Indeed, the Cardinal-Primate of Poland, August Hlond, claimed that the massacre had not been racially motivated, and that, in any case, if there

was

some anti-Semitism in society this was largely the fault of ‘Jews who today occupy leading positions in Poland’s government’.

49

Local and national Communist leaders responded a little more helpfully - by prosecuting some of the main participants and by providing protection and a special train to take the wounded away to Łód – but on the day itself they remained mute. The reason given by the local party secretary was that he ‘didn’t want people to be saying that the [Party] is a defender of Jews’.

– but on the day itself they remained mute. The reason given by the local party secretary was that he ‘didn’t want people to be saying that the [Party] is a defender of Jews’.

50

The Interior Minister, Jakub Berman, who was himself Jewish, was informed of the pogrom while it was still going on, but also rejected suggestions that radical measures should be taken to stop the mob. Thus even the highest authority in the land proved himself unable, or unwilling, to help. Just as in Hungary, the Polish Communists – even the ones who were Jewish – were keen to distance themselves from any possible association with the Jews.

The reaction to the anti-Semitic violence in eastern Europe was dramatic. Many survivors who had gone back to Poland after the war now returned to Germany on the grounds that it was safer in the country that had originally persecuted them than it was at home. The stories they told dissuaded others from making the same journey. ‘Whatever you do, don’t go back to Poland,’ was the advice given to Michael Etkind. ‘The Poles are killing all the Jews returning from the camps.’

51

Harry Balsam was told the same thing: ‘They said that we must be mad to want to go back as they were still killing Jews in Poland … They told us the Poles were doing what the Germans could not manage, and that they had been lucky to come out alive.’

52

As early as October 1945, Joseph Levine of the Joint Distribution Committee was writing to New York that ‘everyone reports murder and pillage by the Poles and that all the Jews want to get out of Poland’.

53

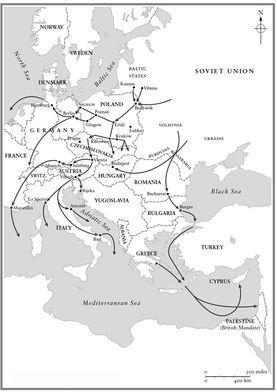

Fortunately for many Polish Jews, and indeed Jews from several other countries in eastern Europe, an escape route had been set up for them. In the aftermath of the war, groups of determined Jews had set up an organization called Brichah (‘Flight’), which had begun to secure a whole series of safe houses, methods of transport and unofficial border crossing points in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania. At first they had been a very clandestine organization, smuggling truckloads of Jews across borders by bribing guards with money and alcohol, but by 1946 they had attained a semi-official status amongst the governments of eastern Europe. In May that year the Prime Minister of Poland, Edward Osóbka-Morawski, stated openly that his government would not stand in the way of Jews who wished to emigrate to Palestine – an assertion he repeated after the Kielce pogrom.

54

In the aftermath of the pogrom, a formal border crossing point was negotiated between one of the commanders of the Warsaw ghetto uprising, Yitzhak ‘Antek’ Zuckerman, and the Polish Defence Minister Marian Spychalski. Other prominent people associated with Brichah organized similar border crossings with the Hungarians, the Romanians and the American authorities in Germany, and the Czechs agreed to supply special trains for the transport of Jewish refugees across the country.

55

The numbers of Jews fleeing westwards were significant, but they increased dramatically in the aftermath of the Kielce pogrom. In May 1946 Brichah organized the flight of 3,502 people from Poland. This rose to approximately 8,000 in June. But in July, after the pogrom, the figures more than doubled to 19,000, and then almost doubled again to 35,346 in August, before falling back to 12,379 in September. These figures do not include the 10 – 20,000 who fled Poland by other means, including putting themselves in the hands of private speculators and smugglers. In addition, the Joint Distribution Committee in Bratislava reported that some 14,000 Hungarian Jews had fled through Czechoslovakia in the three months after Kielce. In total, between 90,000 and 95,000 Jewish refugees are thought to have fled from eastern Europe in July, August and September 1946.

56

The total number of Jews who fled west in the two years after the end of the war is probably in the region of 200,000 from Poland, 18,000 from Hungary, 19,000 from Romania, and perhaps a further 18,000 from Czechoslovakia – although most of this last group were forced out not because they were Jewish but because the Czechs considered them German.

57

When one also factors in the 40,000 or so Jews who fled the same countries in the years 1948 – 50, we reach a grand total of almost 300,000 people who were forced to leave their countries because of anti-Semitic persecution. This is, if anything, a slightly conservative estimate.

58

Where did all these Jews go? In the short term they aimed for the displaced persons camps in Germany, Austria and Italy; but the irony that it should be these former Axis countries that would provide them with salvation did not escape them. Their long-term aim was to leave mainland Europe altogether. Many wanted to go to Britain or parts of the British Empire; many more wanted to get to the United States; but by far the majority wanted to go to Palestine. They knew that Zionists were pushing for a Jewish state there, and considered such a state the only place where they might realistically be safe from anti-Semitism.

They were helped in this aim by just about every nation apart from Britain. The Soviets, who were perfectly happy for their Jews to flee Europe, did not place obstacles in their way and opened their borders for Jews – but only Jews – to exit. The Poles and the Hungarians, as we have seen, did whatever they could to make life for Jews uncomfortable, and again encouraged them to leave by any means possible. The Romanians, Bulgarians, Yugoslavs, Italians and French all provided ports for Jews to embark on ships bound for the Holy Land, and rarely made any effort to stop them. But it was the Americans who helped the Jews most of all – not by allowing them to come to the United States, but by facilitating their journey towards British-controlled Palestine. They exercised considerable diplomatic pressure on the British to get them to accept 100,000 Jews in Palestine, despite the fact that they themselves officially allowed only 12,849 Jews into America under President Truman’s special DP directive.

59

The British were the only ones who tried to stem the flow of Jews from the east. They pointed out that the vast majority were not survivors of Hitler’s concentration camps, but Jews who had spent the war in Kazakhstan and other areas of the Soviet Union. Since it was now supposedly ‘safe’ for them to return to their home towns, the British did not see why they should be the ones to provide sanctuary for them - the Soviet Union and the countries of eastern Europe should also be doing their fair share. While they were happy to provide shelter for Hitler’s victims in Germany, they drew the line at welcoming a new wave of Jewish refugees that had little to do with the war. Unlike the Americans, they refused these new Jews entry to the DP camps under their control.

The British believed – wrongly, as it turns out – that this new wave of Jewish refugees was inspired not by fear of anti-Semitism but by Zionists who had travelled from Israel to eastern Europe in order to agitate for recruits to their cause. In fairness to the British, the Brichah movement was indeed made up mostly of Palestinian Zionists – but they were entirely mistaken in their assumption that the new desire to flee to Palestine had originated with them. As historians like Yehuda Bauer have conclusively shown, the impetus to flee came exclusively from the refugees themselves: all the Zionists were doing was providing them with a place to aim for.

60

The British also argued passionately that it was morally wrong, particularly in the aftermath of the Holocaust, to allow the flight of European Jews towards Palestine. According to the Foreign Office, it was‘surely a counsel of despair … indeed it would go far by implication to admit that [the] Nazis were right in holding that there was no place for Jews in Europe’. The British Foreign Secretary himself, Ernest Bevin, strongly believed that ‘there had been no point in fighting the Second World War if the Jews could not stay on in Europe where they had a vital role to play in the reconstruction of that continent’ .

61

For all their appeals to moral philosophy, the real reasons behind British reluctance were political: they did not want to create a potentially explosive situation between Arabs and Jews in the Middle East. But without the robust cooperation of any of their partners in Europe there was not really much they could do to prevent the westward flight from continuing. Their efforts to prevent Jews from arriving in Palestine were a little more successful, and ships in the Mediterranean carrying tens of thousands of Jewish immigrants were boarded by the Royal Navy and redirected to special DP camps in Cyprus.

5. The Jewish flight to Palestine

But this was merely a case of King Canute trying to hold back the tide – in the end there was little the British could do to stop the course of events. In the summer of 1946, Zionists began a campaign of terror against the British in Palestine (a campaign that was the main cause of the rise of anti-Semitism in postwar Britain). The following year the British started to scale down their military presence in Jerusalem. At the end of November 1947, after intensive lobbying by Zionists, the United Nations voted to award part of Palestine to the Jews for the formation of their own state. And finally, in 1948, after a close-run civil war between the Jews and Arab Palestinians, the state of Israel was consolidated. The Jews were free to make one small corner of the world their own.

This is not the place to embark on a discussion of the brutal conflict that has existed between Israelis and Arabs ever since that time, and which continues to fill our newspapers today. Suffice it to say that the Jews were presented with an opportunity that was too great to pass up. Given their recent history, one can hardly blame them for wishing to create their own state, even if, in the words of one Palestinian historian, the Arabs ‘failed to see why they should be made to pay for the Holocaust’.

62

For better or worse, huge numbers of European Jews at last found themselves in a country where they themselves were the masters, where they could not be persecuted, and where they would be allowed to follow their own agenda. Israel was not only the promised land, but a land of promise.