Sacred Trash (20 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

“Notes on the Jews in Fustat from Cambridge Genizah Documents” was, as its title suggests, extremely gestational, and Worman’s tone was a bit cautious as he put forth the simple but—for the time—rather audacious notion that “from the business documents that come from the Genizah … many facts come to light which may serve to unveil something of the history of the Jewish race in a large city where they abode in great numbers, were very wealthy, and had much to endure.” After tapping several classical Arabic chronicles for a précis of the history of Fustat from its founding in 640 to its conquest by the Fatimid (Shiite) caliphate in the second half of the tenth century, he proceeds to offer a rough sketch of the medieval Jewish parts of town: he accounts for the two Rabbanite synagogues located there—the synagogue of the Jerusalemites (or Palestinians, that is, Ben Ezra) and the synagogue of the Iraqians (also known as the Babylonians)—as well as the nearby Karaite synagogue. He gestures to the rabbinical courts and attempts to account for some of the officials whose names are mentioned in legal documents found in the Geniza. He lists a number of the Fustat markets (including the Big Market, the Market of the Perfumers, the Market of the Steps, and the Markets of Saffron, Wool, Linen, and Cotton). He then describes the oldest part of town, the fortress called Qasr ash-Sham‘ (known variously in English as the Fortress of the Romans, the Greeks, Babylon, or the Lamp), which is where the Ben Ezra synagogue is situated and which, together with an adjoining Jewish neighborhood known as Musasa, he characterizes (not entirely correctly) as “the ‘ghetto’ of Fustat.” Musasa, he writes, was also home to “the mart of the Jews” and the chief location for the mills and millers. While the picture of Jewish Fustat that takes shape here is still very crude, and riddled with basic mistakes, the roughest outlines of the city begin in Worman’s account to appear—word by word, line by line, fragment by fragment, like a blurred photograph gradually emerging in its developing fluid.

Worman went on to publish several other articles on related subjects, but he seems soon to have realized that his true gift lay not in scholarship but in bibliography. In Abrahams’s words, “He determined to qualify himself for a task which he foresaw must be undertaken by himself if it were to be undertaken at all.” The Geniza collection, Worman understood with uncanny prescience, would be next to worthless without a catalog.

That was easier said than done. As he set out to make sense of, and give form to, the mass of disparate paper and vellum scraps that formed the collection, the technically untrained Worman—working in almost complete isolation and with little precedent to follow—faced an enormous task that required not only advanced knowledge of several languages, expert paleographic skills, and superior eyesight, but an almost bottomless well of patience. (A devout Christian, Worman may have had the words of the Gospel of John in mind as he labored: “Gather up the

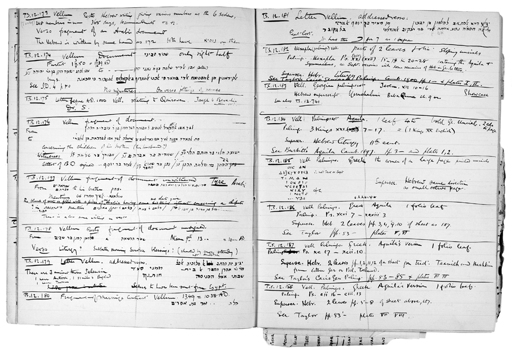

fragments that nothing be lost.”) Hebrew, Judeo-Arabic, Aramaic, Arabic, and Worman’s own English translations and descriptions all crowd together in the inky scrawl he left behind on hundreds of slips of paper and in six plain marble notebooks that contain his draft handlists of all the fragments preserved in glass and some of those bound in volumes—about twenty-five hundred pieces in all.

A typical page of one of Worman’s handlists looks something like a working lab notebook, in which one can trace the arc of an experiment through the scientist’s deliberate notations, scribbled figures, and blotchy scratch-outs. In its text-crammed and sometimes hard-to-decipher yet strangely

animate

way, it also bears a peculiar resemblance to a leaf from the Geniza:

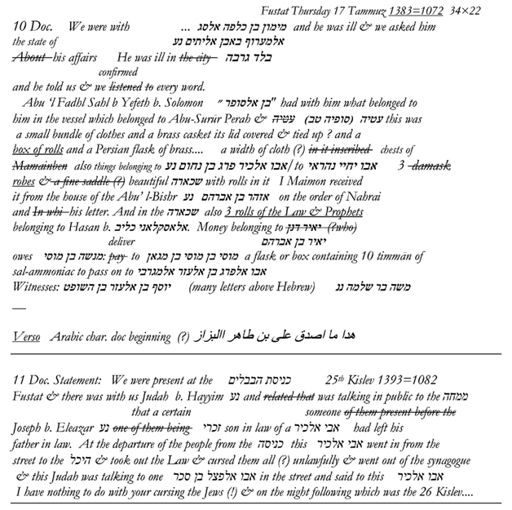

Compiled between 1906 and 1909, this first, fledgling handlist of Geniza manuscripts remains the only catalog of this part of the collection. And though some of the information contained there has since been superseded, corrected, or greatly expanded upon by more recent and informed readings, it offers a remarkable microcosm of the Geniza world and its riches, and shows Worman anticipating—really intuiting—a whole century of study.

Besides these chaotic drafts, Worman managed to complete two “finished” handlists, which contain brief descriptions of some of the documents, calligraphed immaculately in his fine Victorian cursive. His premature death, however, brought the process of cataloging to an abrupt halt: the bulk of the Cambridge collection would remain unclassified for another sixty years. But the descriptions that Ernest Worman left behind in that small pile of tattered notebooks would prove a great help to several others toiling in the mine.

T

he Polish-Jewish historian Jacob Mann, for instance, seems to have made excellent use of that handwritten legacy. Mann arrived in England from Przemysl, Galicia, in 1908—just a year before Worman’s death—and while Mann had access to Worman’s notebooks, it appears the two never met, a fact that somehow suits this, the loneliest period of Geniza research. If it wasn’t every man

for

himself, it was certainly every man

by

himself.

That may have been the way Mann preferred it. Remembered by an acquaintance as “one of the shyest men I have ever known,” he comes across in his own voluminous writings as stern, pedantic, and chronically humorless, rigid in his commitment to what he dubbed “a cautious and laborious inductive method.” If that doesn’t sound like a lot of fun, it must be said that the same characteristics that would have made Mann, one imagines, a singularly insufferable dinner guest may also be what rendered him precisely the (exacting, unsentimental) scholar the

field

needed

at this stage. Mann’s was “the genius of indefatigable and herculean industry,” in the words of one admirer, who also praised his “infinite painstaking care and patience.”

Raised in a household of Belz Hasidim by a ritual-slaughterer father who would offer his sons anatomy lessons based on the inner organs of a cow, Mann was considered a religious prodigy and began from an early age to study secular subjects—modern Hebrew literature, German, philosophy, and astronomy. He was by nature wary and withdrawn: it has been said that the “caution in relation to other people and the isolation” that marked him as a young man later gave way to “excessive … distance from his colleagues.” But his aloof bearing may also have derived from an understandable instinct for self-preservation.

At age twenty, Mann convinced his father to let him travel to London to avoid the draft; they had, after all, cousins in England—and religiously observant cousins at that. In fact, Mann planned to study at both the liberal Jews’ College and secular London University, and soon after his arrival, the London branch of the family picked up and moved to Antwerp, leaving him completely on his own. Impoverished, largely friendless, and new to the English language, Mann poured himself into his studies during these years, only to be pronounced an enemy alien during World War I and threatened with deportation. He had, however, already been recognized as a scholar of exceptional promise, and after the chief rabbi of England, Joseph Hertz, and the head of Jews’ College, Adolph Büchler, intervened with the authorities, it was agreed that Mann could stay in London if he would report twice daily to the police.

Perhaps it was Büchler—penny-pinching Oxford librarian Adolf Neubauer’s nephew and protégé—who first steered Mann toward the Geniza’s untapped documentary wealth and encouraged him to take on the project that began as his dissertation and, with its 1920 publication as a book, constituted the first major historical work based on Geniza documents.

The Jews in Egypt and in Palestine under the Fatimid Caliphs

became, according to one later scholar, “a classic almost immediately

after its publication.” Subtitled

A Contribution to Their Political and Communal History Based Chiefly on Genizah Documents Hitherto Unpublished,

this two-volume tome charted a much more expansive realm—both physically and chronologically—than any previous modern account of medieval Middle Eastern Jewish history: Worman’s inching attempts to enumerate the synagogues and markets of Fustat had given way to Mann’s wide-ranging effort to chart Jewish life across the heart of an empire. By his own account, Mann had “practically gone through the whole Cambridge collection from one end to another” (wearing, it seems, a homemade gas mask, to protect himself from the fumes), and had done much the same with the Geniza holdings at the Bodleian, the British Museum, and in the private collection—then housed in London—of that early Geniza explorer, the lawyer Elkan Adler. Yet in his typically tiptoeing way Mann insisted that “no claim is put forward of having exhausted all the available material. As with the nation of Israel, so with its literature—‘scattered and separated among the peoples.’ ”

His book presented, according to Mann, an “attempt … to reconstruct the life of these Jewries [of Egypt and Palestine] from the beginning of the Fatimid reign in Egypt (969 C.E.) till about the time of Maimonides, who died at the end of the year 1204 C.E.” But it was, he warned, just a start. Before all else, he needed to establish the most basic cast of characters and outline of the period. “It is my sincere hope that, as more of the Genizah fragments see the light of publication, the skeleton presented here will … clothe itself in flesh and blood and approach the stage of completion.”

To his credit, Mann understood both the overwhelming scope of the task he had set himself and the limits of his own powers. He had made it his business to present a tremendous amount of “new” documentary material by offering in raw form the transcriptions of hundreds of mostly Hebrew fragments (communal appeals, elegies for public figures, formal “epistles,” letters to and from religious leaders) plucked from the Geniza and never before published. “In Geniza research, quantity is quality,” in the words of S. D. Goitein, the century’s greatest explorer of the documentary Ben Ezra material. The difference between the interpretation of a single, isolated fragment and the analysis of a much larger accumulation of manuscripts relating “to the same period, the same person, the same phenomenon” was essential. Mann’s triumph lay, first of all, in the sheer scale of his undertaking.

His success also derived from his ability to arrange these sources in some comprehensible order, and in doing so, to delineate a pivotal period in Jewish history, what Goitein called “the time when everything in Judaism became consolidated, crystallized, and formulated.” And Mann’s reading of the texts in question entailed a major historical revision: before him, the Gaonim, or presidents of the two talmudic academies of Babylonia (in the towns of Sura and Pumbedita), had been considered the leaders and sages of all the world’s Jews. In Mann’s version—based not on canonical religious literature or official histories but on the messier, accidental evidence found in the Geniza—the life of Jewish Palestine and the academy

there

was suddenly thrust into focus. Despite endless political and military upheavals, Jews had, it became clear, continued to live and flourish in the Holy Land, and the Gaon of Jerusalem had in fact been the leading Jewish authority in the Fatimid Empire. Mann’s book was, in this sense and according to Goitein, “a revelation. It reclaimed pre-Crusader Palestine for Jewish history.”