Sacred Trash (35 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

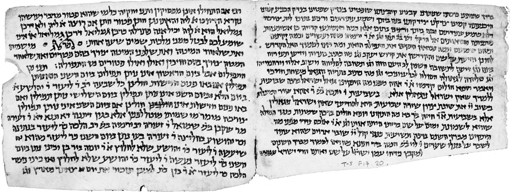

Among the other important subjects that have, alas, been given short shrift in our book are many standard rabbinic modes. Key Geniza fragments expose, for instance, previously unknown (and sometimes mystical) midrashim, as well as a cacophony of legal responsa, dispatched by the heads of the academies in Babylonia and Palestine and by later halakhic authorities to correspondents scattered throughout the Jewish world—from Lucena to Aleppo to Kairouan. These scribbled replies to queries posed from far away offer a fascinating and previously obscured angle onto the medieval rabbis’ unedited, unabridged opinions about a sprawling range of topics pertaining to Jewish law as it was actually—not theoretically—practiced. Moving back still further in time, the Geniza also provides us with a Talmud that is—at least visually—not at all talmudic. These early Talmud fragments predate the now-familiar arrangement of a central text surrounded by a constellation of commentaries, and present what

looks

like a more straightforward, if still charged and not-always-easy-to-follow argument. The older versions of the text bring scholars closer than ever before to the origins of this classic expression of Jewish thought—especially as we find it in the Palestinian Talmud, which Schechter described as “in some respects more important for the knowledge of Jewish history and the intelligent conception of the minds of the Rabbis than the ‘twin-Talmud of the East,’ ” the Babylonian version. The Palestinian Talmud had been, however, seriously

neglected over the centuries and therefore “little copied by the scribes.” The Geniza, as Schechter saw right away while leaning over the Egyptian tea chests, would “open a new mine in this direction.”

Sexy subjects such as grammar, lexicography, and paleography have likewise been treated only in passing here, as have various historical topics—including Jewish life in Crusader Palestine and the legendary Jewish kingdom of the Khazars. As with so many other Geniza matters, documentary evidence about the Khazars sends us back to some of the most basic questions about Judaism, including perhaps

the

most basic one: Who is a Jew and how did he or she become one? From an early discovery by Schechter of what appears to be a tenth-century letter that details Khazar history to an important 1962 find of an epistle concerning the medieval Khazar community of Kiev (the earliest known mention of that city in any language), the Geniza has furnished us with convincing evidence of the existence of this legendary and isolated Jewish kingdom of Turkic converts between the Black and the Caspian seas.

And neither last nor least of the major topics untouched upon in this book, the Geniza holds a store of detailed and often intimate information relating to one of the greatest figures of the medieval Jewish day—the philosopher and communal leader Moses (Musa) ben Maimon, or Maimonides, whose somewhat tortured son appears in our final chapter. The Geniza has yielded more than sixty fragments in the philosopher’s own handwriting, including marked-up “draft copies” of his famous

Mishneh Torah

(which was, controversially, intended to replace the Talmud as a core text for study). These drafts are full of crossed-out words and second thoughts—revealing what we might think of as either a perfectionist, conscientious, neurotic, or simply human side of the Rambam. The Geniza has also preserved moving examples of his personal correspondence (to, among others, his beloved traveling-businessman brother, David—who eventually drowned in the Indian Ocean) and numerous specimens of his dashed-off responses to petitioners’ questions about Jewish law. At the same time, we see Maimonides the Jewish physician at work, as the Geniza has left us a letter of application to apprentice with Dr. Maimonides, and some of his handwritten prescriptions, including aids to digestion and what appears to be a kind of medieval Viagra, an iron-water-based concoction designed to boost male potency. The Geniza also lets us know that, despite his generally party-squashing, stoic philosophical tendencies, the Rambam seems if nothing else to have been liberal with prescriptions of wine, the curative powers of which he apparently held in high esteem. In fact, the Geniza provides the equivalent of an entire medieval

Physicians’ Desk Reference,

describing in precise detail the cause, diagnosis, and treatment of diseases; the preparation of a Mediterranean medicine chest of potions, pills, pastes, ointments, lotions, and gargles; and even the social and ethical aspects of the medical profession.

Alongside this largely unexplored mountain range of fragments relating to the principal modes of medieval Jewish life in the East, the Geniza

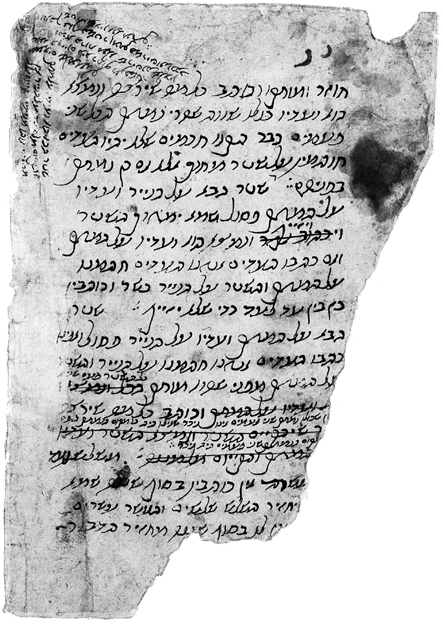

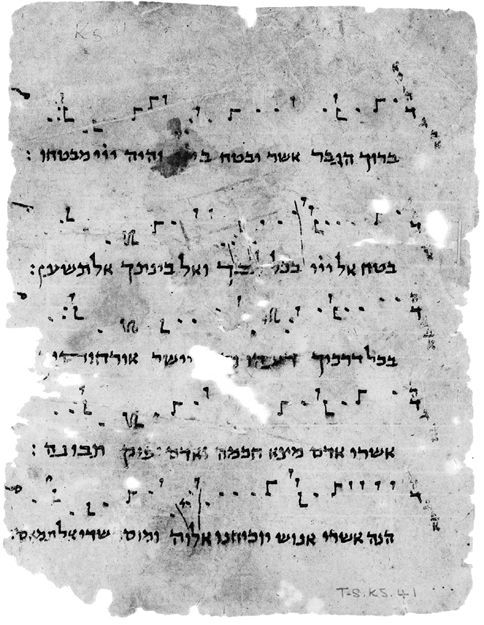

has turned up a number of curious though by no means trifling items among its foothills. The earliest known piece of Jewish musical notation surfaces there, for example—in manuscripts left by one Obadiah, a messianically minded early-twelfth-century ex–Norman monk of southern Italian origin who converted to Judaism and eventually settled in Fustat. And further testament to the Geniza’s ability to blindside us are two of the world’s oldest Yiddish documents, which were probably left behind by Ashkenazic visitors to Egypt: a fourteenth-century 420-line anonymous poem in rhymed quatrains about Abraham’s destruction of his father’s idols, the story of which is told in considerable (midrashic) detail and with what at times seems almost a kind of slapstick humor—and, from the Middle High German epic tradition, a Yiddish narrative poem that has no German analogue and is therefore invaluable for the study of early German literature.

In a much lower Yiddish register, Geniza scholars have found a group of letters from a sixteenth-century Jerusalemite named Rachel Zussman to her grown businessman son Moshe in Cairo. Among the earliest examples of Yiddish letter-writing, and clearly part of a much more extensive correspondence, they tell of the once well-off but now struggling Prague-born woman’s complicated relationship with her only child. Apart from warning him to watch over his money carefully and (above all) to keep up his studies, and also not to be proud when he does something good and of course to write her more often—she wastes little time before pressing the inevitable buttons: “God knows what will become of me,” she moans, adding that she has already spent such and such amount this month and has had to borrow money from her own grandson, but

God will help me, and all [the people of] Israel in the future.… Don’t worry, my son. I always ask God that you not be sick and that I suffer in your stead. And I also ask that He not let me die before I see your face again and you lay your hands over my eyes.… Don’t worry, my son … but don’t come now. [The situation, she explains, isn’t good.] Don’t worry, my son, … if I died I would not have a sheet to be brought down from my bed in … and I don’t have a cover for my head. If you can, buy me one, cheaply.… Come back to the holy city.

W

hile one would think that our Fustat closet contained a finite amount of material, the end of which will soon be reached, the history of scholars’ finds does make one wonder. Within the last decade or two a striking array of discoveries have proven that the Geniza stock is far from spent.

Just a few months back (we write in the first weeks of 2010), a fragment was found by a T-S Genizah Unit researcher that completes one of those previously extant Yiddish epistolary fragments and helps us understand the thrust of an otherwise hard-to-decipher letter from Rachel Zussman—which turns out, once again, to be her complaint that her son hasn’t written, that his silence is making her suffer, and that she thinks he’s wasting his time in Cairo and would do better for himself (learn more and make a better living) if he moved back home, to Jerusalem. One is tempted to declare “Jewish mothers and their sons” a new Geniza field altogether—between the apple of Wuhsha’s eye and a letter from an aristocratic elderly mother who, writing in Judeo-Arabic from Syria in 1067, offers up the familiar and almost conventional complaint that her son hasn’t been in touch for months: “I get letters from your brother, may God preserve him, but don’t find any from you among them.… Nothing less than a letter from you will cheer my spirits. Do not kill me before my time! … I fast and pray for you night and day.”

And then, in classic medieval and also inimitable Jewish maternal fashion she animates the convention with a marvelous leap to the particular, pleading with him: “By God, … send me your worn and dirty shirts to revive my spirit.”

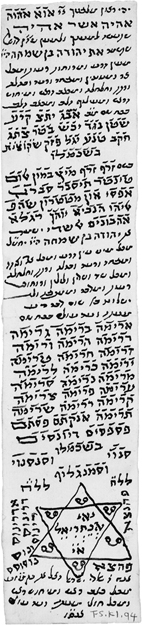

Also forced to stand brooding off to the side not only of our book, but of the entire field of Geniza studies for much of the previous century, is the long-scorned subject of magic and mysticism—with its incantations, fumigations, talismans, angels, curses, and cures. Such texts were widespread in medieval Jewish society, and thousands of “magical” pages exist in the Geniza, though they have been examined in serious scholarly fashion only since the 1980s. A particularly spicy specimen of this sort was encountered not long ago—a multilingual curse that begins in Judeo-Arabic, “Take a plate of lead and write on it in the first hour of the day; bury it in a new grave which is three days old,” then moves into Hebrew and Aramaic, in which it addresses by name specific angels (Anger, Wrath, Rage, Fury, and the Destroyer), adjuring them to “blot out the life of N. son of N. from this world” (the victim’s name is to be filled in by the one who utters the curse). A short sentence in Arabic (and Arabic characters), in a different and later hand, follows as a kind of postoperative report, observing that “it’s effective for killing.” Other magic fragments outfit us with recipes for sleep, fishing, ease in childbirth, expelling mice from a

home, making people shudder in a bathhouse, and causing a would-be beloved’s heart to burn with desire.

Quietly spectacular finds have emerged of late beyond the main collections as well. In 2002, a tin box containing 350 Geniza pages was found almost by chance in the Geneva Public and University Library. Archivists came across it while going through the papers of a noted Swiss scholar who had purchased the fragments together with Greek papyri in Cairo at the end of the nineteenth century. The top of the box bears a faint ink inscription that begins “Textes hébraïques … Provenant de la Synagogue du Vieux Caire” and goes on to tell us that the manuscripts were purchased by Jules Nicole in 1896–97 and identified in part by his son Albert Nicole.