Sacred Trash (14 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

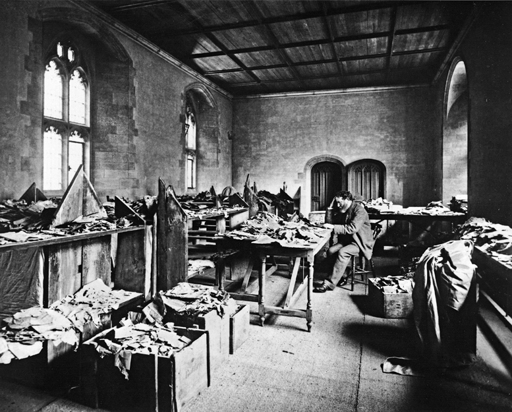

That revelation did not come suddenly, of course, but was the product of slow and extremely painstaking labor on the part of many people. In the now-iconic photograph taken of Schechter “at work” in the Geniza room that month, we see a man entirely alone, his brow resting on one hand—a rabbinic version of Rodin’s

The Thinker—

as he contemplates a single scrap and seems to bear the entire weight of Jewish history on his sloped shoulders. He is surrounded on all sides by papery chaos: it is as though a tornado or a flood had just blasted through a huge stationery store. Yet Schechter sits still, like Prospero having tamed a phenomenal tempest.

The photograph was, as it happens, staged (there is, you will notice, no nose-bag in sight), and we know that Schechter was not often by himself in the room, which had quickly become a popular Cambridge “attraction” where visitors would often drop by to see the Romanian wonder in action: one of them described how “he may be found almost at any hour of the day deeply engaged in sorting and examining his fragments, with an expression in his face constantly changing from disappointment to rapturous delight.” When a guest came to call he would

“tak[e] them from box to box, pointing out to them the significance of this or that MS. or the peculiarity of the specimens of Hebrew writing which lie scattered about on the long tables.”

But more than visitors, Schechter had partners. As he himself had grown to understand perhaps better than anyone, this was not work for one person. “The Geniza is a world,” he wrote, “with all its religious and secular aspirations, longings, and disappointments, and it requires a world to interpret a world, or at least a large staff of workers.” Among the most committed of Schechter’s collaborators was Charles Taylor, who was responsible for sorting the postbiblical Hebrew fragments and palimpsests, and he came almost daily to the Cairo room “to revel there,” as Schechter put it, “in the inspection of the faded monuments of the Jewish past. This was probably the only sightseeing in which he ever indulged.” Agnes and Margaret, meanwhile, took on the task of sifting through the Syriac fragments, another Cambridge professor studied the Greek, and outside experts—one a lecturer in Arabic and Syriac from

Jews’ College in London, the other a Cambridge-trained Jewish convert to Christianity (later ordained an Anglican priest)—were hired to handle, respectively, the Arabic and Judeo-Arabic fragments and the Hebrew Bible pages. At the same time, Jenkinson helped Schechter sort “select fragments” into drawers and oversaw the work of Andrew Baldrey, an employee of the library bindery, who had been assigned the task of cleaning and smoothing the fragments and placing them between glass.

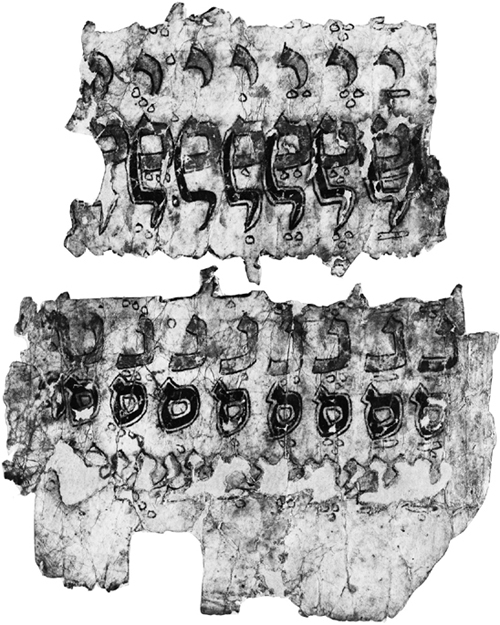

And so on—and on. “The day is short and the work is great,” quoted Schechter, in an 1898 sequel to his “Hoard of Hebrew Manuscripts,” a wide-ranging progress report in which he surveyed more of the gems he’d plucked from the piles over the course of the previous year: leaves with gilt letters; children’s primers; shorthand Bibles, which featured what is called trellis writing (“In the beginning, G. c. the h. a. the e.”); pages of Mishna and other compilations of Oral Law; a papyrus hymnal; as well as copious historical material, especially from the period between the birth of the towering communal and intellectual figure Saadia Gaon in 892 and the death of Maimonides at the start of the thirteenth century. This era, wrote Schechter, “forms, as is well known, one of the most important chapters in Jewish history.” But that chapter would now require serious revision, as “any number of conveyances, leases, bills, and private letters are constantly turning up, thus affording us a better insight into the social life of the Jews during those remote centuries.”

He was not exactly complaining, but even as he rehearsed these discoveries, there was a new tone of melancholy fatigue creeping into Schechter’s words. Since his return from Egypt, he had devoted himself

to the Geniza night and day, sun and snow—sacrificing his health and working himself past the point of exhaustion. He suffered especially in the winter, when his work was slowed to a snail’s pace by the lack of artificial light at the library. He was, he wrote to Sulzberger, red-eyed after a mere hour’s sorting, and forced to bathe his eyes in lotion. One “very dark” day he walked the two miles from his house to the library and “was unable to read a single fragment on account of the fog. It was never as bad as this minute.”

The irony, though, was this: as Schechter had come to grasp the truly miraculous magnitude of the Geniza, he had also begun to recognize the limits of his own strength—and to see, perhaps, the sun setting on his own role in the history of the Geniza’s retrieval. “It will,” he admitted, “occupy many a specialist, and much longer than a lifetime.” And he had other matters to attend to besides. In a strange twist of fate, the very same day that Jenkinson supervised the opening of the first Geniza crate at the library, Schechter had been approached with a tentative offer to become chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. He would eventually take the job (of JTS president)—driven by a number of factors, including his sense that he was underappreciated by the powers that be at Cambridge. Upon his return from Cairo, he had been named curator of the Oriental Department at the library, given a small raise, and awarded an honorary degree, but as Mathilde wrote, “some felt it keenly that … if he had been a member of the Church of England he would have got a bishopric.” There was, then, the related and more

substantive question of his growing alienation from British Jewry and the non-Jewish milieu in which he found himself in Cambridge. (“Life among the goyim means spiritual death to me,” he wrote at one low point, and at another painful moment he wondered aloud, “What shall become of my children in this wilderness?”) Most pressing of all, Schechter felt honor bound to serve. “Believing as I do,” he explained, “in the future of Judaism in America, I think it is my duty to be with my people where I may become some influence for good.”

Perhaps he had also taken to heart the admonitions of his old friend, student, and patron Claude Montefiore, who was extremely critical of the price his work on the Geniza had exacted from Schechter’s scholarly writing, and even went so far as to declare that if it had cost him his great work on theology, he wished the Geniza “had been burnt” before Schechter had ever come across it. “You think me a Philistine. Not so. But it makes me unutterably sad when I see your unique powers not turned to noble account.” This was shortsighted of Montefiore: Schechter’s unique powers had certainly been turned to noble account through his work on the Geniza, but—after five years of sorting manuscripts—he himself clearly sensed it was time for something else. Or something more.

Even though he was glad to be leaving England behind, Schechter’s sense of debt to his friends in Cambridge was great. So many people there had helped him during what was perhaps the happiest and most fruitful period of his life. And though as the blustery Eastern European Jew surrounded by all these hushed-voiced, well-bred Englishmen he’d occasionally acted the bull in a china shop, he was one sensitive bull. In a letter to Jenkinson, composed shortly after he’d announced his resignation, which would take effect at the end of the Lent Term in March of 1902, he wrote in his emotive scrawl to thank the librarian for “the many kindnesses you have shown me during the last ten years. I only hope I have not drawn too much upon your patience and good will. But the

times, especially since my return from Egypt, were not quite normal[,] my excitement finding expression in the most curious ways and counting upon your forbearance.”

Among the many gifts that were showered on Schechter upon his departure were a complete set of the Babylonian Talmud, a clock that rang the Cambridge chimes, and—from Agnes and Margaret—a silver kiddush cup engraved with the words of Ben Sira that they had discovered together: “Happy is the man who meditates on wisdom and occupies himself with understanding.” He was lauded in speeches and toasted at banquets—at one of which he responded by quoting his hero Abraham Lincoln’s farewell address, delivered in Springfield in February of 1861, before he traveled to Washington to assume the presidency: “No one not in my situation can appreciate my feeling of sadness at the parting.… Here I have lived nearly twenty years, and have passed from young man to old man. Here my children have been born. I now leave not knowing when, or whether even, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which has rested on me.” He went on, as Lincoln had, to wish for the assistance of “Him Who can go with me and remain with you, and be everywhere for good” as he bid them all “an affectionate farewell.”

He had not, as it happens, completely left the Geniza behind, but arranged to have sent to his Manhattan address 251 pieces—41 in glass and 210 unbound. Neither had he cut off contact with his Cambridge friends and colleagues. In October of 1902, still settling into his new home and job, he wrote to Jenkinson to reassure him that the fragments he’d borrowed had a secure resting place in the “large fireproof safe” the trustees of the Seminary had installed in his house. Like Schechter, they had traveled a long way from that dusty room in Fustat to the crisp air of Morningside Heights.

And though this was a kind of ending, it was also a beginning, as several of the intellectual chain reactions that Schechter had set into

motion during his Cambridge years would—long after he had left for New York and even departed from this world—continue to ripple forward, causing later scholars to look back across the centuries with a new sense of the old. There is, say the rabbis, no early or late in scripture. They seemed (before its time) to have known a thing or two about the Cairo Geniza.

*

The identity of “Suum Cuique” has to this day never been determined, though certain clues would seem to point in the direction of A. E. Cowley, Neubauer’s younger colleague at the Bodleian. (Cowley was also coeditor, with Neubauer, of both the Oxford edition of Ecclesiasticus, published when Schechter was still in Cairo, and that library’s Hebrew catalog.) Not only would he have had good reason to want to defend Neubauer’s—and the Bodleian’s—name, but Cowley was a fellow of Magdalene College, Oxford, which prided itself on a special toast, called “Jus Suum Cuique,” which it had celebrated every October 25 since 1688.

Palimpsests

I

W

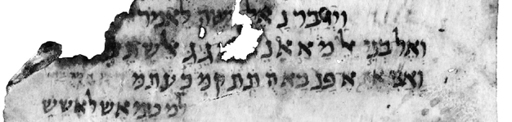

ell before he set sail for Manhattan, Schechter had assigned the sifting of the Greek manuscripts to Francis Burkitt, a rich, good-looking, and eschatologically inclined up-and-coming Anglican scholar of Semitic languages and biblical history. Burkitt had already worked closely, though not without rivalry, alongside the Giblews. In the early 1890s he’d helped Agnes identify the twins’ first and perhaps greatest discovery—the very early Syriac version of the Gospels, which differed in several respects from the canonical text and held out the promise of bringing readers nearer to the actual words and truth of the historical Jesus. But that truth was by no means easy to grasp, since the reddish-yellow ink in which it had been cast constituted the “underwriting” of a palimpsest text—that is, a manuscript that had served double duty, as a kind of medieval Etch A Sketch pad—and had been layered over by a late-seventh- or eighth-century work treating the lives of female saints.